Behind the Camera: A Look at Camera Trap Impacts

July 21, 2020

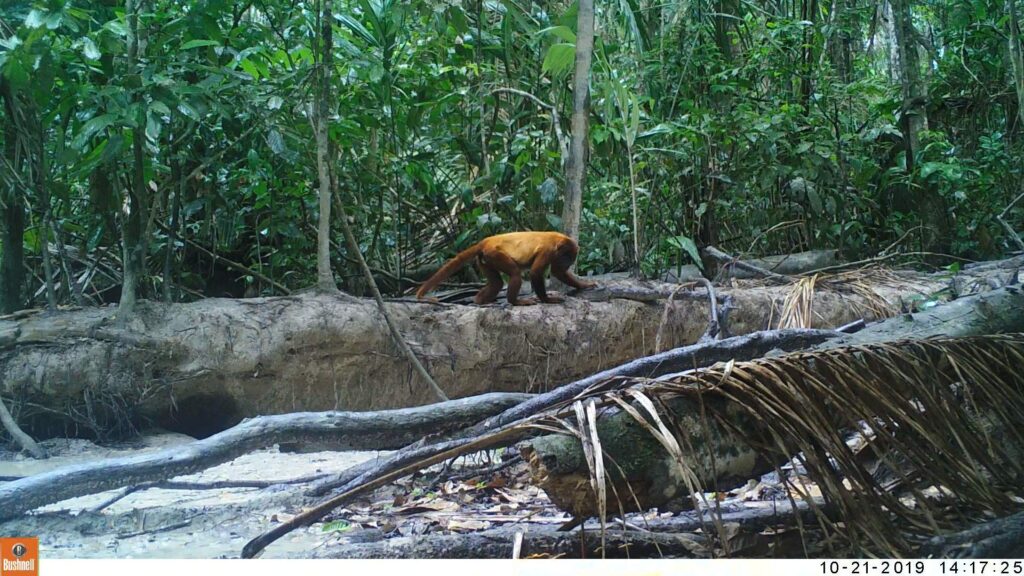

The past few months we’ve featured “Camera Trap Tuesday” on our social media pages, posting glimpses of Amazon animals living their daily lives, freely interacting with each other and their environment when there’s no human presence. But what is the real impact of camera traps? Our camera traps and wildlife conservation expert Nelly Guerra talks about this important initiative; and what it’s like working on our camera trap program in Bolivia with our sister organization Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA. She also recently presented a webinar on the camera trap program in Bolivia, which you can view here.

Benefits of Camera Trap Technology

To begin, Nelly notes that placing camera traps in the forests is the most effective way to record wild species. Images and videos of medium and large-sized mammals commonly elusive to the human eye are recorded in their natural habitats throughout the day and night. Cameras are able to stay out in the field for much longer than a person, be less disruptive, and observe more hours of authentic animal activity. The camera traps are a useful tool to obtain accurate information on the distribution of many species, their abundance, activity patterns, and habitat use. Camera trap management is a key technology that we use to understand the state of biodiversity in an area, which allows us to evaluate key regions to protect and adjust our conservation efforts.

To begin, Nelly notes that placing camera traps in the forests is the most effective way to record wild species. Images and videos of medium and large-sized mammals commonly elusive to the human eye are recorded in their natural habitats throughout the day and night. Cameras are able to stay out in the field for much longer than a person, be less disruptive, and observe more hours of authentic animal activity. The camera traps are a useful tool to obtain accurate information on the distribution of many species, their abundance, activity patterns, and habitat use. Camera trap management is a key technology that we use to understand the state of biodiversity in an area, which allows us to evaluate key regions to protect and adjust our conservation efforts.

A Snapshot of Our Current Implementation

Our camera trap program has been implemented in our areas of work in Bolivia since 2015. We have camera traps placed in:

- TCO Tacana II, an indigenous territory we’ve worked with for decades in the North of the Department of La Paz,

- Santa Rosa del Abuná Integral Model Area, a conservation area we helped create in the department of Pando,

- Manuripi National Wildlife Reserve National Protected Area, an area for conservation we’ve been supporting also in the Department of Pando.

These places have successfully managed to register a wide variety of wild species, several of which had previously been declared as no longer living in the area.

We have recorded many animals in the area that have been categorized as endangered, near-threatened, or vulnerable by the internationally-recognized IUCN Red List of threatened species. This includes the endangered giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), near-threatened jaguar (Pantera onca), bush dog (Speothos venaticus), and harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), as well as the vulnerable white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) and South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris).

Successes of Camera Traps

One highlight of this project has been getting to know an incomparable variety of wildlife. Camera traps have given us data that helps us understand which forests are healthy, because the healthy ones host a great amount of biodiversity.

One highlight of this project has been getting to know an incomparable variety of wildlife. Camera traps have given us data that helps us understand which forests are healthy, because the healthy ones host a great amount of biodiversity.

Another very important accomplishment of working with the camera traps is they have encouraged the inclusion and interest of Indigenous peoples and communities in working with this technology. They provide a way for these communities to monitor the wildlife that exists in their forests and evaluate their conservation status, while at the same time committing to conserving and caring for the Amazon’s wild fauna. For Nelly, “The greatest achievement has been an interest in documenting wildlife through videos and photographs, as well as the interest to develop new camera trap techniques without altering the natural habitat of the species that hide inside our forests.” Getting communities up and close to the animals with whom they share their forest home helps them become more active in their conservation.

Zooming in on the Future

To wrap up, we ask Nelly what she wants others to know about this technology. She replies that, “Working with camera traps is a methodology of gaining conservation information. They are a very useful tool to measure indicators of abundance and distribution of wildlife populations, and obtain data economically without disturbing the natural habitat of wild species. They allow us to analyze the state of conservation of the forests, because the more fauna records collected with the camera traps, the healthier our forests are. Conversely, if you have fewer fauna records that means that our forests are being disturbed by humans and that it makes the fauna migrate to other less disturbed places.”

To wrap up, we ask Nelly what she wants others to know about this technology. She replies that, “Working with camera traps is a methodology of gaining conservation information. They are a very useful tool to measure indicators of abundance and distribution of wildlife populations, and obtain data economically without disturbing the natural habitat of wild species. They allow us to analyze the state of conservation of the forests, because the more fauna records collected with the camera traps, the healthier our forests are. Conversely, if you have fewer fauna records that means that our forests are being disturbed by humans and that it makes the fauna migrate to other less disturbed places.”

If all goes well after the pandemic that we are experiencing, Nelly hopes that this beneficial forest monitoring program can be expanded, and more camera traps could be installed in other key areas. She finishes with a message for young conservationists saying, “I would like to encourage students to work and do wildlife research with camera traps, and learn to perform research on the state of our biodiversity in our Amazon forests.”

Loading...

Loading...