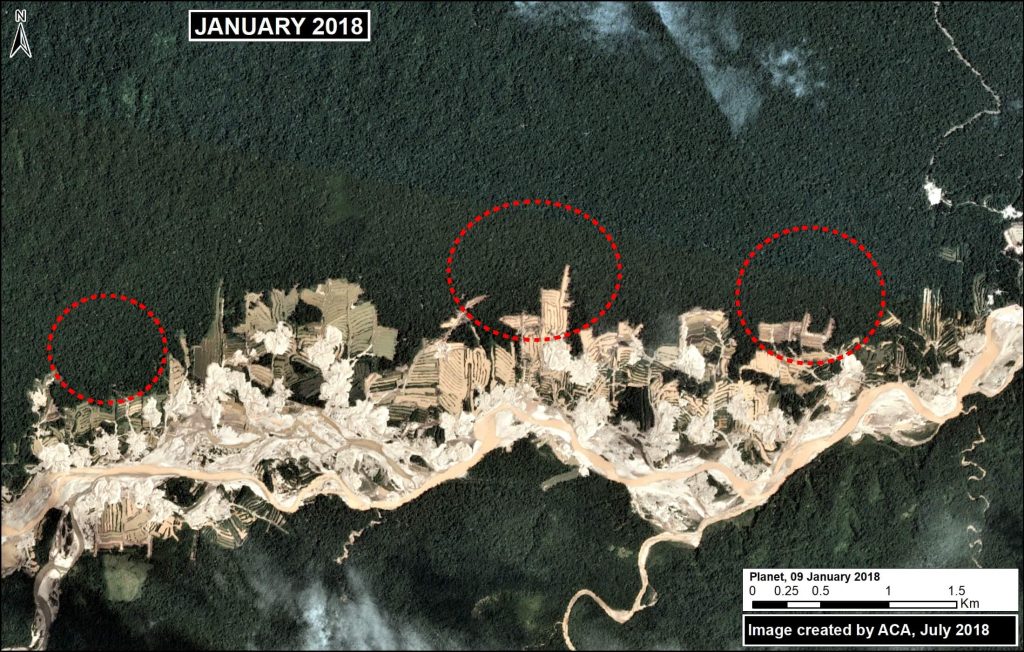

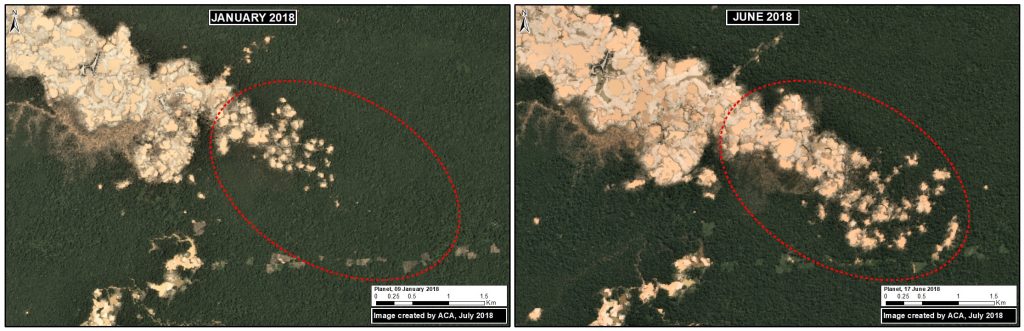

Eastward expansion of La Pampa gold mining. Source: Planet

We have reported extensively on the ongoing gold mining deforestation crisis in the southern Peruvian Amazon (see Archive), estimating the loss of over 17,500 acres in the five years between 2013 and 2017.

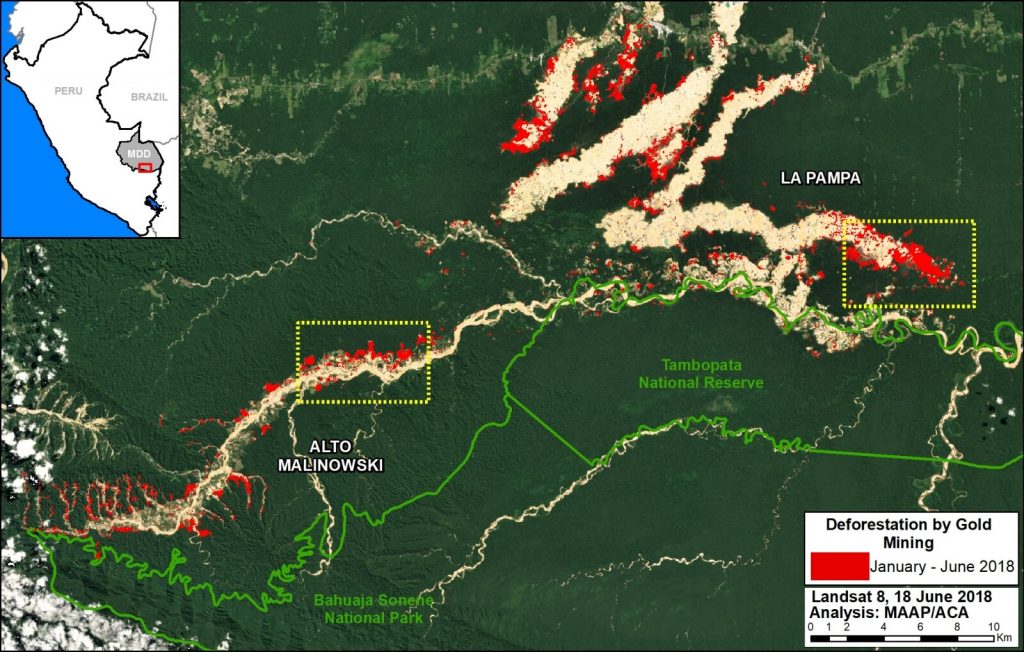

Here, we present new analysis showing that the destruction continues in 2018: we estimate an additional 4,265 acres during the first six months (January – June). This most recent deforestation is concentrated in two critical areas: La Pampa and Alto Malinowski. Most, if not all, of the mining appears to be illegal (see Annex).

This brings the total gold mining deforestation since 2013 to over 21,750 acres.

Next, we show a series of satellite images of the recent deforestation in La Pampa and Alto Malinowski.

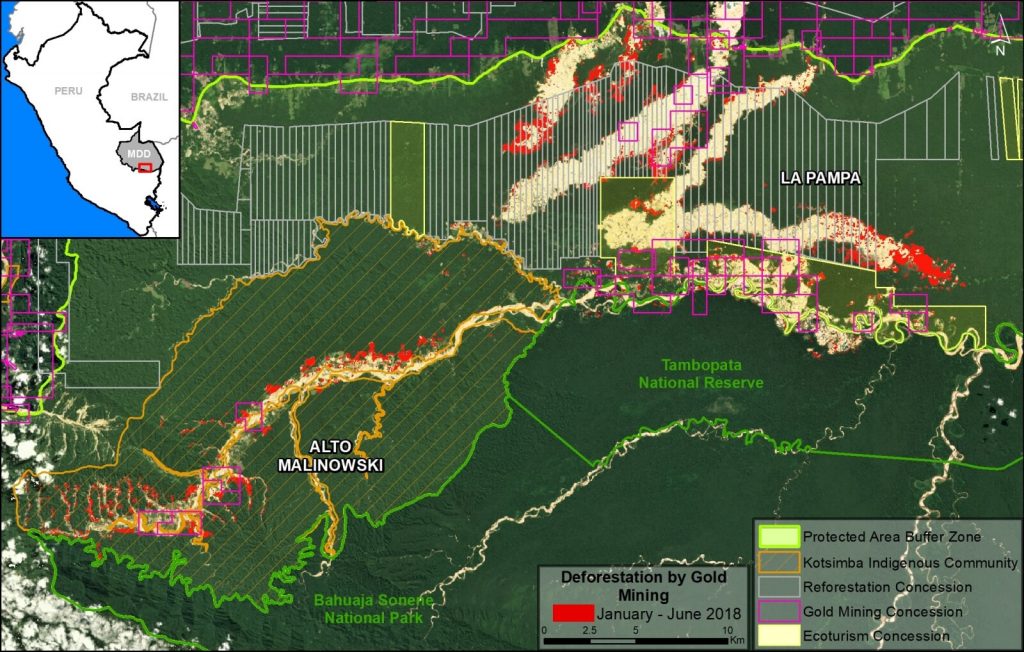

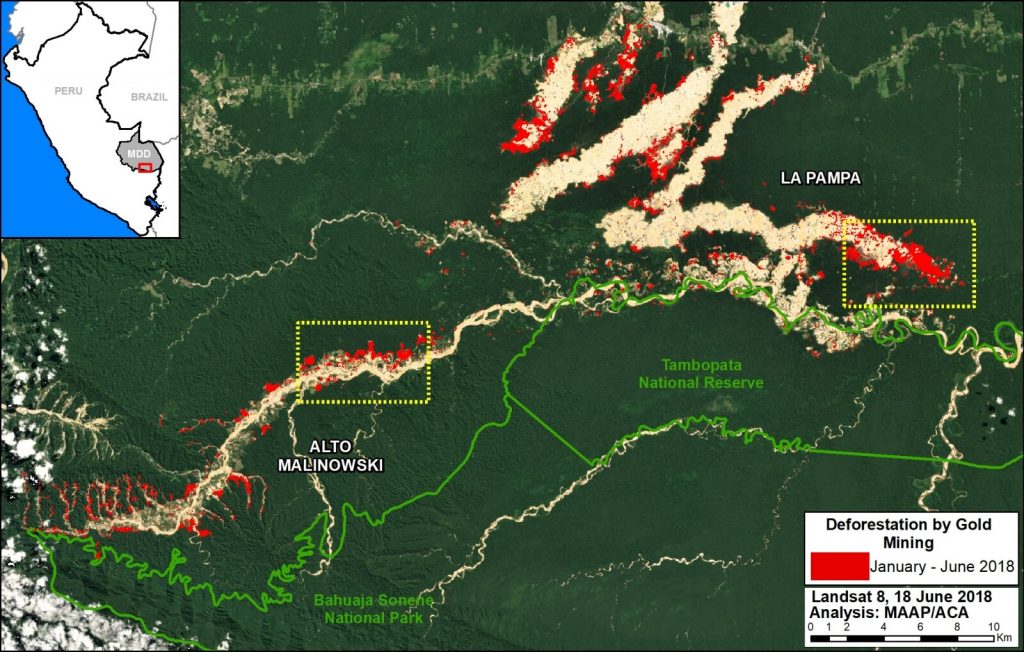

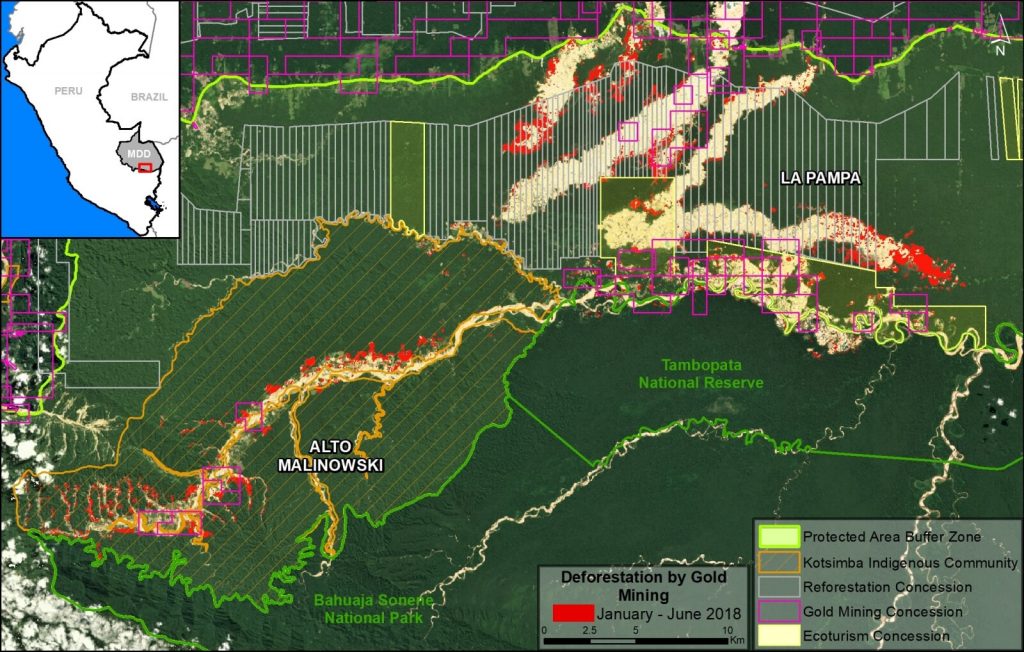

Base Map

The Base Map highlights the most recent (2018) gold mining deforestation in red. We estimate this deforestation to be around 4,265 acres in the two most critical zones: La Pampa and Alto Malinowski. The yellow boxes indicate the location of the zooms described below. At the end of the article, in the Annex, we present the same base map but with all the overlapping land designations as well to illustrate the complexity of the situation.

Base Map. 2018 gold mining deforestation in southern Peruvian Amazon. Data- Planet, UMD:GLAD, MINAM:PNCB

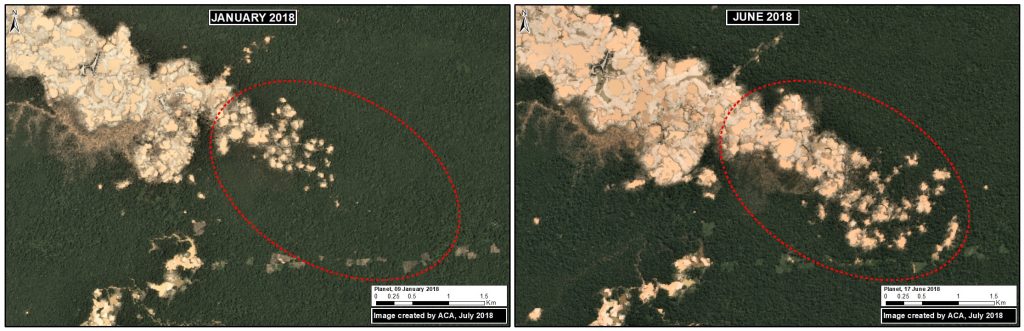

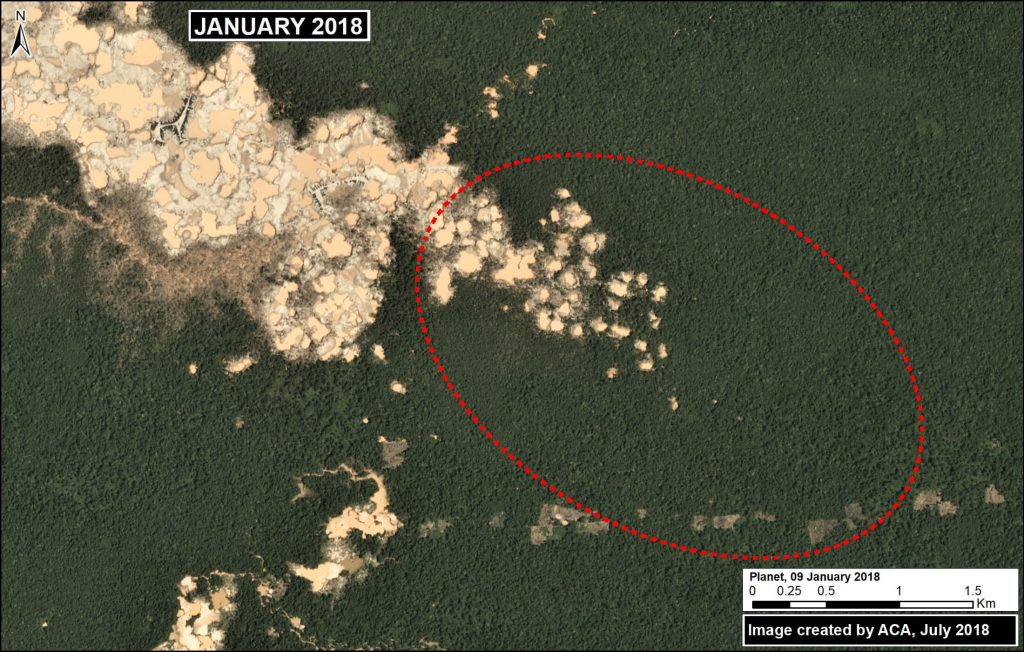

La Pampa

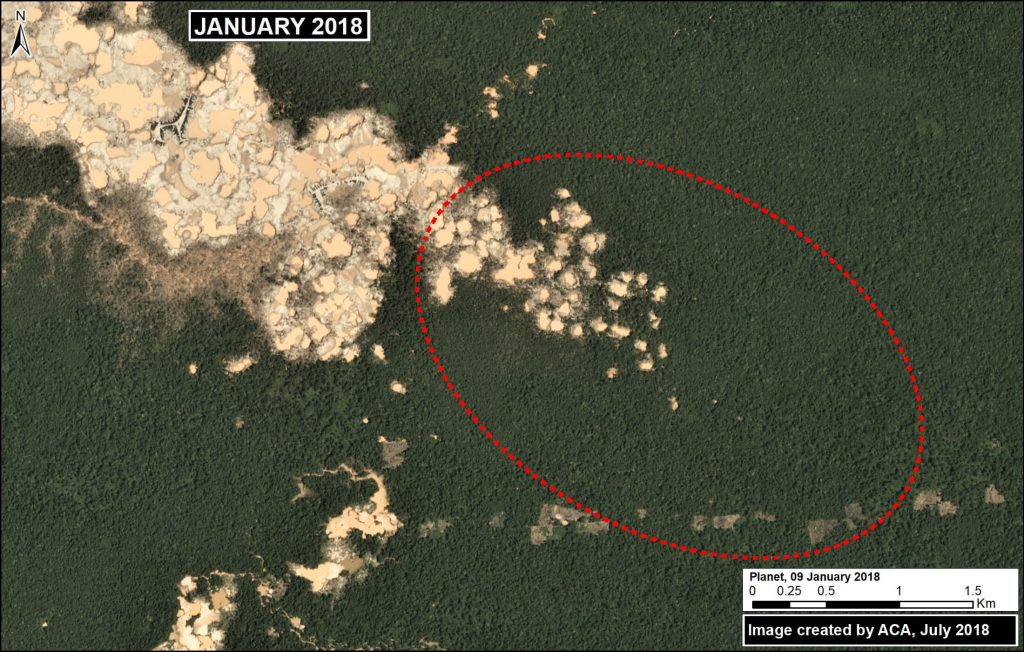

The following images show the gold mining deforestation in the area known as “La Pampa” between January (left panel) and May (right panel) 2018. Note that the second image is in slider format.

Zoom de La Pampa. Datos- Planet, MAAP_1

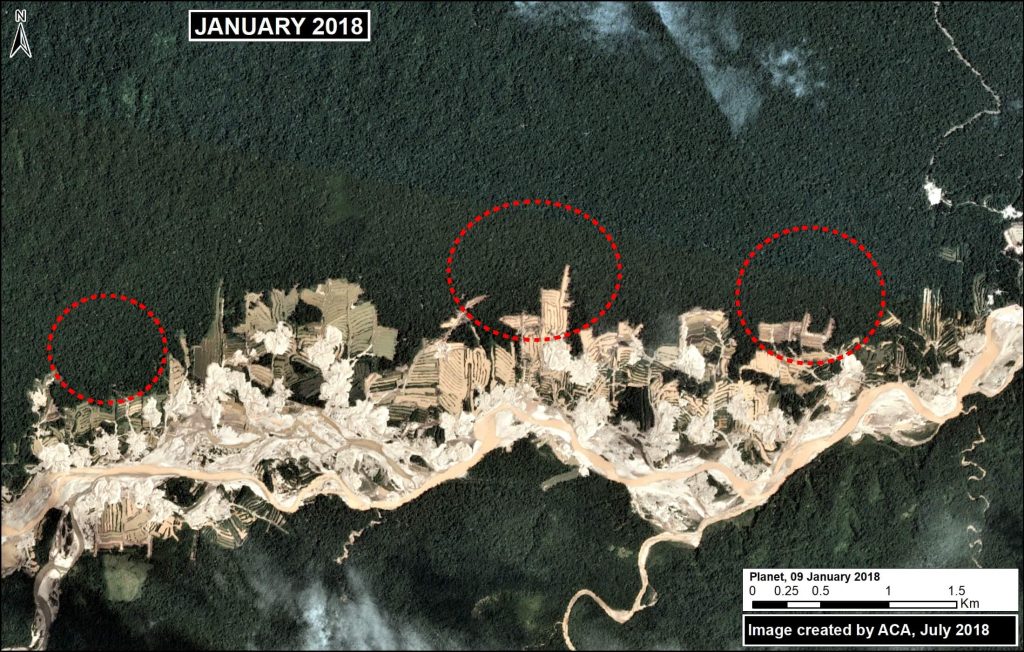

Alto Malinowski

The following images show the gold mining deforestation in the area known as “Alto Malinowski” between January (left panel) and May (right panel) 2018. Note that the second image is in slider format.

Annex

We present the same base map as above, but also with relevant land designations. Note that much of the deforestation is concentrated in forestry concessions (ironically, in “reforestation” concessions) and in the Kotsimba Native Community, both of which are outside the legal mining corridor and within the buffer zones of Tambopata National Reserve and Bahuaja Sonene National Park. Thus, most, if not all, of the mining activity appears to be illegal.

Citation

Finer M, Villa L, Mamani N (2018) Gold Mining continues to ravage the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 87.

Loading...

Loading...