“The tipping point is here, it is now. A modern vision of the Amazon must include truly innovative elements to create profitable bioeconomies that would immediately eliminate illogical and short-sighted economies.”

-Thomas Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, renowned climate scientists

On September 22, we hosted the webinar panel “Building a Forest-Based Economy in the Amazon”, where a panel of international speakers discussed what it takes to build a profitable bioeconomy that keeps the Amazon standing for generations to come, as part of Global Landscape Forum’s “The Tipping Point” conference. Local community members, Indigenous Peoples, and international experts covered three main topics:

- Production Capacity and Market Connections

- Scaling Up

- Building Climate Resilience and Adaptation

Click here to see the full agenda or here to download the presentations (original presentation languages only).

John Beavers, the Executive Director of Amazon Conservation, opened the session affirming how a forest-based economy is a key conservation and development method. “From our view, the local & national economy can sustainably optimize the use of healthy forests as a path to a just and prosperous way of life, and for the effective conservation of the Amazon at scale through a great bioeconomy.”

Thomas Lovejoy, a renowned conservation biologist nicknamed “the Godfather of Biodiversity”, reminded viewers of the ecological importance of the Amazon, highlighting that it makes half of its own rainfall and we are at a tipping point close to where there isn’t sufficient moisture for the Southern and Eastern Amazon to support rainforest. “The solution,” he said, “is to bring back the capacity of the forest to generate moisture, which relates to the new vision of forest-dependent Amazon economies that do not require replacement of forests by large-scale plantations.” He also highlighted the construction of transportation infrastructure and the importance of communication with people on the ground. “We must engage in the local discussions about the infrastructure projects, and what are good and not good ways to go about them, so that wherever the bad ideas begin, there will be a local and informed populace that can argue against them.”

Thomas Lovejoy, a renowned conservation biologist nicknamed “the Godfather of Biodiversity”, reminded viewers of the ecological importance of the Amazon, highlighting that it makes half of its own rainfall and we are at a tipping point close to where there isn’t sufficient moisture for the Southern and Eastern Amazon to support rainforest. “The solution,” he said, “is to bring back the capacity of the forest to generate moisture, which relates to the new vision of forest-dependent Amazon economies that do not require replacement of forests by large-scale plantations.” He also highlighted the construction of transportation infrastructure and the importance of communication with people on the ground. “We must engage in the local discussions about the infrastructure projects, and what are good and not good ways to go about them, so that wherever the bad ideas begin, there will be a local and informed populace that can argue against them.”

Production Capacity and Market Connections

During the first of three sections, panelists covered how local people are building their capacity to sustainably produce from the forest and create market connections that optimize production and increase incomes from forest-friendly commodities. Marcos Terán, Executive Director at Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA, our sister organization in Bolivia, introduced this section by highlighting the resources the Amazon provides its countries. “If we are talking about building forest-based economies, we cannot overlook the vast biodiversity of the Western Amazon, which gives us resources that directly relate to the development of Amazonian countries.”

During the first of three sections, panelists covered how local people are building their capacity to sustainably produce from the forest and create market connections that optimize production and increase incomes from forest-friendly commodities. Marcos Terán, Executive Director at Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA, our sister organization in Bolivia, introduced this section by highlighting the resources the Amazon provides its countries. “If we are talking about building forest-based economies, we cannot overlook the vast biodiversity of the Western Amazon, which gives us resources that directly relate to the development of Amazonian countries.”

One example of a community doing this is Porvenir, in the Bolivian Amazon. Gresley Justiniano, the mayor of this town and the youngest mayor in Bolivian history at 26 years old, discussed how one of their municipal development strategies is to build an economy based on Amazonian products such as açaí, as the region where she is mayor is home to the 79,000-acre Porvenir Conservation Area, an area we helped establish last year. With these resources, they are looking to access larger markets through a better fruit transformation process, sanitary certification, and improved harvesting practices. She also adds that, “our town’s location allows us to access different markets…This allows us to strengthen productive chains and diversify to other Amazonian fruits such as palma real and majo.”

The next speaker was Sara Hurtado, a Brazil nut concessionaire and entrepreneur from the Peruvian Amazon. She is also the manager of the Peruvian Brazil Nut Industry (INCAP in Spanish) and spoke about the benefit of sustainable harvesting, partnering with harvester associations, and Brazil nuts’ importance as a non-wood product that doesn’t result in deforestation. Sara also mentioned how they are working to be resilient to climate change, saying, “We know that climate change will affect Brazil nut production in Madre de Dios and the world. That’s why harvesters are organizing to

The next speaker was Sara Hurtado, a Brazil nut concessionaire and entrepreneur from the Peruvian Amazon. She is also the manager of the Peruvian Brazil Nut Industry (INCAP in Spanish) and spoke about the benefit of sustainable harvesting, partnering with harvester associations, and Brazil nuts’ importance as a non-wood product that doesn’t result in deforestation. Sara also mentioned how they are working to be resilient to climate change, saying, “We know that climate change will affect Brazil nut production in Madre de Dios and the world. That’s why harvesters are organizing to  strengthen our work in the field. We monitor our land to prevent…deforestation, and reforest with Brazil nuts.”

strengthen our work in the field. We monitor our land to prevent…deforestation, and reforest with Brazil nuts.”

The last speaker of the section was Daniel Larrea, the Science and Technology Program Coordinator for Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA. He provided statistics about Brazil nut capacity in Bolivia, such as that there are 20 million Brazil nut trees in the country valued at USD 130-135 million per year, with 87,000 people participating in their harvest. But, he emphasizes that this productivity is dependent on the well-being of the Amazon. “Maintaining a healthy forest is the first step to keeping it productive, to strengthen the livelihoods of local communities. If a forest is healthy, it is productive, it is resilient to the effects of climate change.”

Scaling Up

The following section covered how to scale locally-based production so that it covers the entire Amazon, through strengthening local producer associations and indigenous federations. Isabel Castillo, Country Director of NESsT Peru introduced this section and discussed investment in the Amazon, and how we have to start speaking the language of the two worlds of the financial system. “As facilitators our role is in the world of investment–traditional & nontraditional, but it is also to help local entrepreneurs go national & see their avenue of options to be able to do business.”

The following section covered how to scale locally-based production so that it covers the entire Amazon, through strengthening local producer associations and indigenous federations. Isabel Castillo, Country Director of NESsT Peru introduced this section and discussed investment in the Amazon, and how we have to start speaking the language of the two worlds of the financial system. “As facilitators our role is in the world of investment–traditional & nontraditional, but it is also to help local entrepreneurs go national & see their avenue of options to be able to do business.”

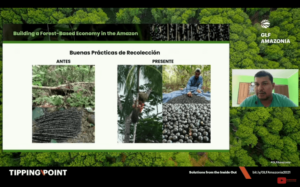

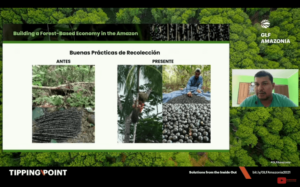

Eiji Misael Campos Fernandez was the first speaker of the section, and he currently serves as the President of the Departamental Federation of Açaí and Amazonian Fruits of Pando (FEDAFAP) in Bolivia, a regional association representing rural families and farmers across the Pando Department. He noted the importance of advancing sustainable harvesting saying that, “it is very important. In the Pando department, what was done before was not sustainable…palmera was being lost in this region. Today we have good harvesting practices.” He also emphasized the importance of working within associations, and how they help meet the objectives set for forest concessions.

Eiji Misael Campos Fernandez was the first speaker of the section, and he currently serves as the President of the Departamental Federation of Açaí and Amazonian Fruits of Pando (FEDAFAP) in Bolivia, a regional association representing rural families and farmers across the Pando Department. He noted the importance of advancing sustainable harvesting saying that, “it is very important. In the Pando department, what was done before was not sustainable…palmera was being lost in this region. Today we have good harvesting practices.” He also emphasized the importance of working within associations, and how they help meet the objectives set for forest concessions.

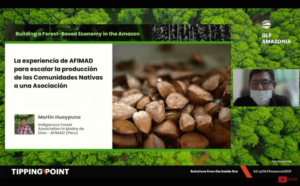

Martin Huaypuna, the President of the Indigenous Forest Association in Madre de Dios (AFIMAD), spoke next. Based in Puerto Maldonado, Peru, AFIMAD represents seven indigenous communities from the lower Madre de Dios river area who are dedicated to sustainable Brazil nut production. He discussed some lessons learned so far, saying that, “Being an Association has made us stronger, before we were victims of intermediaries, now we can negotiate better with buyers and generate greater volume. Although there is little financing for our activities, we finance ourselves with: contributions from partners, we manage loans with international and national entities, though help is always welcome…Now we are better at conserving our forests.

Martin Huaypuna, the President of the Indigenous Forest Association in Madre de Dios (AFIMAD), spoke next. Based in Puerto Maldonado, Peru, AFIMAD represents seven indigenous communities from the lower Madre de Dios river area who are dedicated to sustainable Brazil nut production. He discussed some lessons learned so far, saying that, “Being an Association has made us stronger, before we were victims of intermediaries, now we can negotiate better with buyers and generate greater volume. Although there is little financing for our activities, we finance ourselves with: contributions from partners, we manage loans with international and national entities, though help is always welcome…Now we are better at conserving our forests.

Building Climate Resilience and Adaptation

The last of our three topics covered at the conference covered some of the ways in which communities are building resilience and adaptation into their forest management and production. James Hardcastle, the Associate Director of IUCN, introduced the section, noting the importance of scaling up through local channels whether that be through local harvesters’ associations or non-governmental organizations on the ground. “When we think of bioeconomy and we think of scaling up we tend to think of volume and finance…but really what we need to see scaling up is the connection to approaches and organizations, to see scaling up as growing something from strong roots…This really means public and private investors need to incorporate these elements that we’re facing, this ability to support good governance and scaling up through the local channels, local connection, peer to peer knowledge and local agents and information flow…bioeconomy is built on financing the whole resilience.”

The last of our three topics covered at the conference covered some of the ways in which communities are building resilience and adaptation into their forest management and production. James Hardcastle, the Associate Director of IUCN, introduced the section, noting the importance of scaling up through local channels whether that be through local harvesters’ associations or non-governmental organizations on the ground. “When we think of bioeconomy and we think of scaling up we tend to think of volume and finance…but really what we need to see scaling up is the connection to approaches and organizations, to see scaling up as growing something from strong roots…This really means public and private investors need to incorporate these elements that we’re facing, this ability to support good governance and scaling up through the local channels, local connection, peer to peer knowledge and local agents and information flow…bioeconomy is built on financing the whole resilience.”

The first presenter of the section was Hilda Maria Cordero, the first woman President of Ese Eja Infierno, an indigenous community close to Puerto Maldonado in the Peruvian Amazon. She gave firsthand accounts of how her community has noticed the difference in weather patterns the past few years, likely as a result of climate change. “The dry season is getting drier, there are days that reach 104° F (40 °C) at noon…and Brazil nut production has changed a lot. There are years when production drops a lot and affects us economically. In the dry season, the smoke that comes from Brazil and Bolivia (from the fires) reaches Madre de Dios. This affects people (vision, lungs) and we do not know

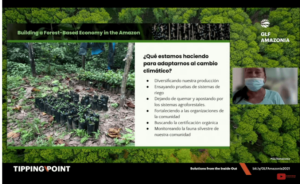

The first presenter of the section was Hilda Maria Cordero, the first woman President of Ese Eja Infierno, an indigenous community close to Puerto Maldonado in the Peruvian Amazon. She gave firsthand accounts of how her community has noticed the difference in weather patterns the past few years, likely as a result of climate change. “The dry season is getting drier, there are days that reach 104° F (40 °C) at noon…and Brazil nut production has changed a lot. There are years when production drops a lot and affects us economically. In the dry season, the smoke that comes from Brazil and Bolivia (from the fires) reaches Madre de Dios. This affects people (vision, lungs) and we do not know  how it is affecting crops or wildlife.” However, she also noted how they’re adapting to this current situation and supporting forest-based economies, saying, “We are empowering community organizations so they can negotiate with buyers and get better prices, and are seeking the organic certification of our agricultural products to have a sustainable production and to be able to enter better markets.”

how it is affecting crops or wildlife.” However, she also noted how they’re adapting to this current situation and supporting forest-based economies, saying, “We are empowering community organizations so they can negotiate with buyers and get better prices, and are seeking the organic certification of our agricultural products to have a sustainable production and to be able to enter better markets.”

Adivaldo Moura Silva, the Director of the Amazon Productive Development Service of Integral Technical Assistance (SEDEPRO in Spanish), which is part of the local Pando, Bolivia government spoke about what his community is doing to be resilient to climate change. Pando spans 156 million acres (63 million hectares), with 84% of its surface being Amazon forest. “We are implementing mechanisms that contribute to the mitigation & adaptation to climate change, through the sustainable management of our forests and Mother Earth,” which includes coordination between public and private sectors, and the diversification of the use of Amazonian fruits.

Closing

A fter a brief question-and-answer session, Fabiola Muñoz, the Former Minister of Environment and Agriculture for Peru, closed the session with the main takeaways from this session. She noted how information to local actors is a key element, with another being financing. “We cannot advance without accessible financing. We also have to work on financial inclusion…show what it is possible that these are truly scale-ready profitable businesses. We have to learn to grow, and we have to start speaking this language of the two worlds of the financial system. We also have to work on financial inclusion, and show that these are truly scale-ready profitable businesses.” She also concluded on a hopeful note, saying, “I believe that this event has shown us that it is possible to have an economy based on the products of biodiversity.”

fter a brief question-and-answer session, Fabiola Muñoz, the Former Minister of Environment and Agriculture for Peru, closed the session with the main takeaways from this session. She noted how information to local actors is a key element, with another being financing. “We cannot advance without accessible financing. We also have to work on financial inclusion…show what it is possible that these are truly scale-ready profitable businesses. We have to learn to grow, and we have to start speaking this language of the two worlds of the financial system. We also have to work on financial inclusion, and show that these are truly scale-ready profitable businesses.” She also concluded on a hopeful note, saying, “I believe that this event has shown us that it is possible to have an economy based on the products of biodiversity.”

Thank you to all our participants and panelists for attending our session. To see what other upcoming events there are, please visit amazonconservation.org/events.

The following section covered how to scale locally-based production so that it covers the entire Amazon, through strengthening local producer associations and indigenous federations. Isabel Castillo, Country Director of

The following section covered how to scale locally-based production so that it covers the entire Amazon, through strengthening local producer associations and indigenous federations. Isabel Castillo, Country Director of

“The importance of promoting the integral management of Amazonian forests and supporting the production of Amazonian fruits are activities that keep forests standing in time to improve the quality of life for local communities,” said Marcos Terán, the Executive Director of our sister organization Conservación Amazónica-ACEAA.

“The importance of promoting the integral management of Amazonian forests and supporting the production of Amazonian fruits are activities that keep forests standing in time to improve the quality of life for local communities,” said Marcos Terán, the Executive Director of our sister organization Conservación Amazónica-ACEAA.

Loading...

Loading...