Download PDF of this article

We present a preliminary analysis of current patterns and drivers of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. This analysis is largely based on the first 15 articles published on MAAP between April and September 2015, but also incorporates information from other relevant sources. We describe this analysis as preliminary because as MAAP research continues, we will be able to improve and refine our synthesis in subsequent editions.

Image S1a. Recent patterns and drivers of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. Numbers indicate relevant MAAP article. Data: SERNANP, IBC, MINAM-PNCB/MINAGRI-SERFOR, MAAP.

Introduction & Summary of Key Results

Image S1a illustrates recent (2000 – 2013) patterns of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon based on data from the Peruvian Ministries of Environment[i] and Agriculture[ii]. These two Ministries have documented a total forest loss of around 1.65 million hectares (ha) [4.08 million acres]in the Peruvian Amazon between 2001 and 2014, with an increasing trend in recent years (2014 had the highest forest loss on record with 177,571 ha)[iii],[iv]. Another recent report by the Peruvian government stated that the majority (75%) of the Amazonian deforestation is due to small-scale clearings related to agriculture and livestock activities, usually near roads or rivers[v].

Building off of that historical and annual information, our goal at MAAP is to monitor deforestation in near real-time. Since April 2015, we have published numerous articles analyzing areas in the northern, central, and southern Peruvian Amazon. In this initial analysis, we have found that three of the most important drivers of deforestation are large-scale oil palm (and cacao) plantations, gold mining, and coca cultivation. We also found a growing network of logging roads that contribute to forest degradation. Image S1a displays the general geographic distribution of these drivers of deforestation and degradation.

We estimate that around 30,000 hectares (74,130 acres) of primary forest was cleared since 2000 for large-scale oil palm and cacao plantations. Cacao has recently joined oil palm as a deforestation driver due to the arrival of the company United Cacao and their implementation of the large-scale agro-industrial model in place of traditional small-scale plantations on previously degraded lands.

Gold mining has directly caused the deforestation of over 43,000 ha (106,255 acres) since 2000, mostly in the region of Madre de Dios. In recent years, this deforestation has been concentrated in the Tambopata National Reserve buffer zone.

Although coca cultivation is reportedly declining in Peru, we found that it remains a major driver of deforestation, particularly within and around remote protected areas. For example, we documented 143 ha (353 acres) of coca related deforestation within the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone, and an additional 2,638 ha (6,518 acres) related to shifting agricultural cultivation, which includes coca, within and around Bahuaja Sonene National Park.

We also documented a recent expansion of logging roads in the central Peruvian Amazon. This finding is significant because it is difficult to detect selective logging in satellite imagery, but now we can at least detect the roads that indicate that selective logging is taking place in a given area.

We identified some important geographic patterns related to the four drivers described above. For example, large-scale oil palm (and cacao) are concentrated in the northern Peruvian Amazon, while gold mining deforestation has largely been in the south. Coca-driven deforestation appears to be particularly problematic in the southern Peruvian Amazon, but also exists in the north. The construction of new logging roads is currently most active in the central Peruvian Amazon.

The documented deforestation is caused by both illegal and legal means. For the former, there is extensive deforestation from illegal gold mining and coca cultivation. Regarding the latter, oil palm and cacao companies are exploiting loopholes in the Peruvian legal framework that facilitate large-scale deforestation for agricultural projects.

Large-scale Agriculture (Oil Palm and Cacao)

Image S1b. Large-scale agriculture deforestation in the northern Peruvian Amazon. Numbers indicate relevant MAAP article. Data: SERNANP, IBC, MINAM-PNCB/MINAGRI-SERFOR, MAAP.

Image S1b illustrates that large-scale agriculture (namely oil palm and cacao) is an important cause of deforestation in northern Peru.

Importantly, several oil palm and cacao companies are changing the production model in Peru from small-scale to large-scale agro-industrial. For example, in a recent interview, United Cacao CEO Dennis Melka stated that his company is trying to replicate the agro-industrial model used by oil palm companies in Southeast Asia[vi].

This shift is noteworthy because large-scale plantations usually come at the expense of forests, while small-scale plantations are better able to take advantage of previously cleared lands[vii]. We estimate that over 30,000 hectares (74,100 acres) of primary forest was cleared since 2000 for large-scale oil palm and cacao plantations (see below). Much less primary forest, around 575 ha, was cleared for small-scale oil palm (we have yet to evaluate small-scale cacao).

Note that we emphasize the clearing of primary forest. We conducted an additional analysis to determine whether oil palm (both small and large-scale) and cacao (just large-scale) plantations were originally sited on lands with primary forest, secondary forest, or already deforested. We defined primary forest as an area that from the earliest available Landsat, in this case 1990, was characterized by dense closed canopy forest cover.

The following is a concise breakdown of how we calculated the 30,000 ha (74,100 acres) of primary forest loss from large-scale plantations.

MAAP articles #2, #9, and #13 demonstrated that 2,276 ha of primary forest was cleared by United Cacao between May 2013 and September 2015 outside of the town of Tamshiyacu in the northern Peruvian Amazon (Loreto region).

MAAP article #4 detailed the deforestation of 9,400 ha of primary forest (plus an additional 2,350 ha of secondary forest) between 2011 and 2015 for two large-scale oil palm projects near the town of Nueva Requena in the central Peruvian Amazon (Department of Ucayali).

In addition, yet unpublished MAAP analysis shows that in Palmas de Shanusi/Oriente (oil palm projects operated by the company Grupo Palmas), 6,974 ha of primary forest were cleared between 2006 and 2011, although the legally mandated 30% forest cover reserves were maintained. An additional 8,225 ha of primary forest was cleared in areas immediately surrounding the concessions.

Finally, although not yet published on MAAP, we also documented nearly 3,500 ha of primary forest loss in other large-scale oil palm projects in San Martin and Ucayali regions.

It is important to emphasize that several oil palm and cacao companies are exploiting various loopholes in the Peruvian legal framework that facilitate large-scale deforestation for agricultural projects[viii]. In fact, these companies argue that according to Peruvian law, they are engaged in legal “forest clearing”, not illegal “deforestation”[ix].

Gold Mining

Image S1c. Gold mining deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. Numbers indicate relevant MAAP article. Data: SERNANP, IBC, MINAM-PNCB/MINAGRI-SERFOR, MAAP.

Image S1c illustrates that gold mining-driven deforestation is largely concentrated in the southern Peruvian Amazon, particularly in the region of Madre de Dios and adjacent Cusco.

According to the scientific literature, gold mining deforestation in Madre de Dios increased from 10,000 ha in 2000 to 50,000 ha in 2012[x]. MAAP articles #1, #5, and #12 documented the deforestation of an additional 2,774 ha between 2013 and 2015 in two gold mining hotspots (La Pampa and Upper Malinowski), both of which are located within the buffer zone of the Tambopata National Reserve. In addition, MAAP #6 showed gold mining deforestation expanding from another Madre de Dios gold mining hotspot (Huepetuhe) into the tip of Amarakaeri Communal Reserve (11 ha / 27 acres).

Much of the Madre de Dios gold mining deforestation described above is illegal because it is occurring within and around protected areas where mining is not permitted under the government-led formalization process.

MAAP articles #6 and #14 detailed recent gold mining deforestation in the region of Cusco. Specifically, we documented the deforestation of 967 ha along the Nuciniscato River and its major tributaries since 2000 (with the vast majority occurring since 2010). Much of this deforestation appears to be linked to gold mining.

Thus, the total documented gold mining deforestation in Madre de Dios and adjacent Cusco is at least 53,750 ha[xi], over 80% of which has occurred since 2000. This total is an underestimate since we have not yet done detailed studies for 2013 – 2015 deforestation in all of the known gold mining zones in these two regions.

In addition, MAAP #7 showed two gold mining zones in the region of Ucayali (along the Sheshea and Abujao Rivers, respectively). Much of this deforestation occurred between 2000 and 2012.

Finally, there are also reports of extensive gold mining in northern Peru (the regions of Amazonas and Loreto) but we do not yet have data showing that it is causing deforestation.

Coca

Image S1d. Coca cultivation areas in the Peruvian Amazon. Numbers indicate relevant MAAP article. Data: UNODC 2014, MINAM-PNCB/MINAGRI-SERFOR, SERNANP, NatureServe.

Although the most recent report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) indicates that overall coca cultivation is declining in Peru[xii], our research finds that it remains a major driver of deforestation in certain areas, particularly within and around several remote protected areas.

Image S1d displays the distribution of current coca-cultivation areas (in relation to protected areas) based on the data from the latest United Nations report. Of these areas, we have thus far focused on the three detailed below.

MAAP articles #7 and #8 show recent coca-related deforestation within the southern section of the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone. This area is particularly important because it is soon slated to be upgraded to a national park. Specifically, we documented coca-related deforestation of 130 ha between 2013 and 2014 within the southwestern section of the reserve, and, most recently, a new plantation of 13 ha during June 2015 within the southeast section.

MAAP article #10 revealed that shifting agricultural cultivation, that includes coca, is also a major issue within and around Bahuaja Sonene National Park, located in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Specifically, we found the recent deforestation of 538 hectares (1,329 acres) within the southern section of the Park, and an additional 2,100 hectares (5,189 acres) in the surrounding buffer zone. Much of this deforestation is likely linked to coca cultivation since the latest United Nations report indicates these areas contain high coca plantation densities.

MAAP article #14 documents the deforestation of 477 ha (1,178 acres) along the Nojonunta River in Cusco since 2000 (with a major peak since 2010). Much of this deforestation is likely linked to coca cultivation since the latest United Nations report indicates these areas contain medium to high coca plantation densities.

Logging Roads

Image S1e. Logging roads in the Peruvian Amazon. Numbers indicate relevant MAAP article. Data: SERNANP, IBC, MINAM-PNCB/MINAGRI-SERFOR, MINAGRI, MAAP.

One of the major advances discovered in this work is the ability to identify the expansion of new logging roads. This advance is important because it is extremely difficult to detect illegal logging in satellite imagery because loggers in the Amazon often selectively cut high value species and do not produce large clearings. But now, although it remains difficult to detect the actual selective logging, we can detect the roads that indicate that selective logging is taking place in that area.

Image S1e illustrates the likely logging roads that we have recently detected. Of these areas, we have thus far focused on the two detailed below.

MAAP article #3 shows the rapid proliferation of two new road networks in the northern Peruvian Amazon (Loreto region). Most notably, it highlights the construction of 148 km of new roads, possibly illegal logging roads, through mostly primary forest between 2013 and 2014. One of the roads is within the buffer zone of the Cordillera Azul National Park.

In addition, MAAP article #7 shows the expansion of new logging roads near both the southern and northwestern sections of the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone. In both cases, the expansion is very recent (between 2013 and 2015).

[i] National Program of Forest Conservation for the Mitigation of Climate Change – PNCB.

[ii] Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre – SERFOR

[iii] MINAGRI-SERFOR/MINAM-PNCB (2015) Compartiendo una visión para la prevención, control y sanción de la deforestación y tala ilegal.

[iv] Note that some of the documented forest loss may come from natural causes, such as landslides or meandering rivers.

[v] MINAM (2013) Fondo Cooperativo Para El Carbono de los Bosques (FCPF) Plantilla de Propuesta para la Fase de Preparación para REDD+ (Readiness Plan Proposal – RPP). Link: http://www.minam.gob.pe/cambioclimatico/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/03/R-PP-Per%C3%BA-Final-Dec-2013-RESALTADO_FINAL_PUBLICADA-FCPF_24-febrero.pdf

[vi] NF Joan (2015) United Cacao replicates Southeast Asia’s plantation model in Peru, says CEO Melka. The Edge Singapore.Link: http://www.unitedcacao.com/images/media-articles/20150713-the-edge-united-cacao.pdf

[vii] Gutiérrez-Vélez VH, DeFries R, Pinedo-Vásquez M, et al. (2011) High-yield oil palm expansion spares land at the expense of forests in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett., 6, 044029. Link: http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044029/pdf

[viii] Environmental Investigation Agency (2015) Deforestation by Definition. Washington, DC. Link: http://eia-global.org/news-media/deforestation-by-definition

[ix] Tello Pereyra R (2015) Situacion legal, judicial, y administrativa de Cacao del Peru Norte SAC. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_YIe70u1oA

[x] Asner GP, Llactayo W, Tupayachia R, Ráez Luna E (2013) PNAS 110 (46) 18454-18459. Link: http://www.pnas.org/content/110/46/18454.abstract

[xi] That is, 50,000 ha from the literature and 3,750 ha from MAAP analysis.

[xii] UNODC (2015) Monitoreo de cultivos ilícitos Perú 2014. Link: https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Peru/Peru_Informe_monitoreo_coca_2014_web.pdf

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S (2015) Patterns and Drivers of Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP Synthesis #1. Link: https://maaproject.org/2015/09/maap-synthesis1/

For two decades now, Alessandro Catenazzi, Ph.D., an assistant professor of zoology at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, has been using the ACA biological stations in the Peruvian rainforest to learn more about the frog population in the region.

For two decades now, Alessandro Catenazzi, Ph.D., an assistant professor of zoology at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, has been using the ACA biological stations in the Peruvian rainforest to learn more about the frog population in the region. “Now the creeks are dead zones.”

“Now the creeks are dead zones.”

In April 2015, ACA launched a cutting-edge near real-time deforestation monitoring system for the Andean Amazon known as MAAP (

In April 2015, ACA launched a cutting-edge near real-time deforestation monitoring system for the Andean Amazon known as MAAP (

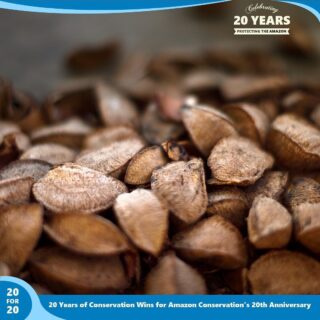

this castañero community, harvesters who provide for their families by sustainably gathering castañas (which we know as Brazil nuts) that have fallen from trees in pristine Amazonian forest, which they then sell to international markets. Their way of life not only provides an income, but leaves the forest completely intact, which benefits all of us by storing carbon, essential to combating global climate change as the world’s leaders recognized in Paris just last week.

this castañero community, harvesters who provide for their families by sustainably gathering castañas (which we know as Brazil nuts) that have fallen from trees in pristine Amazonian forest, which they then sell to international markets. Their way of life not only provides an income, but leaves the forest completely intact, which benefits all of us by storing carbon, essential to combating global climate change as the world’s leaders recognized in Paris just last week.  forest-friendly) source of income.

forest-friendly) source of income.

Last week our Peruvian partner

Last week our Peruvian partner

Loading...

Loading...