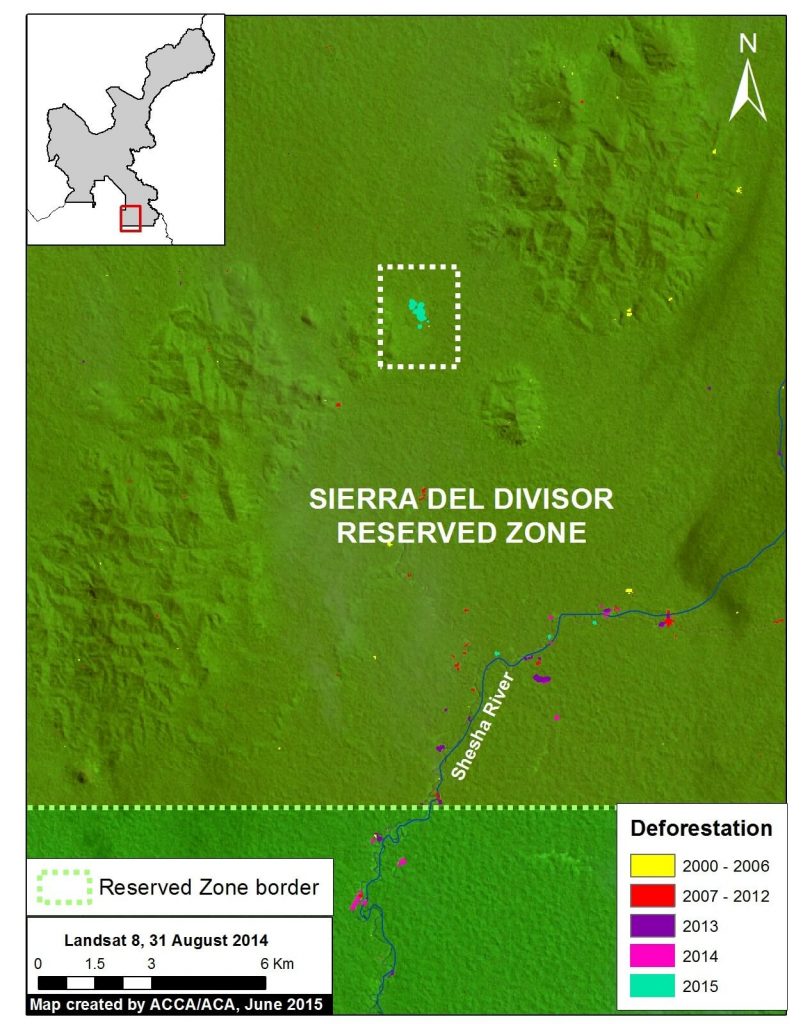

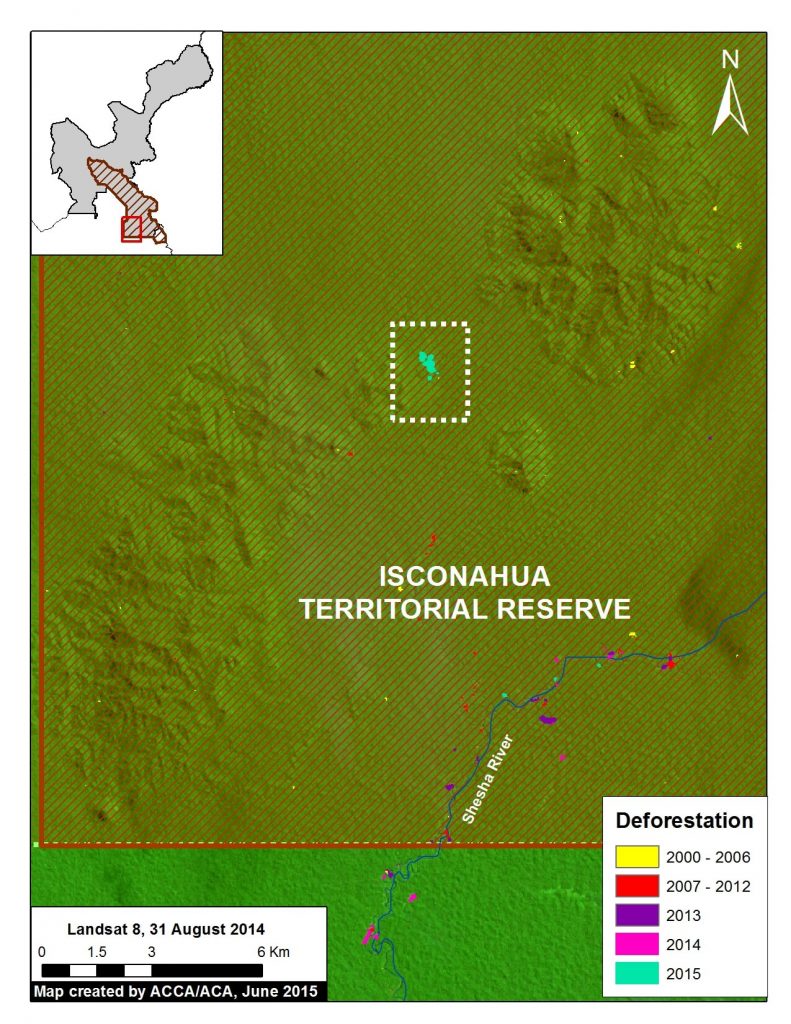

In MAAP #7, we emphasized the need to promote the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone to the category of National Park due to the growing threats within and around the area. Here in MAAP #15, we show how the construction of a new logging road threatens the northwest section of the current Reserved Zone. New high-resolution images reveal that the construction of this logging road has continued to expand in 2015, and now even crosses a corner of the Reserve.

In addition, in anticipation of the upcoming visit of Peruvian President Ollanta Humala to the United Nations in New York to discuss climate change, we present data on the levels of carbon stored in the proposed Sierra del Divisor National Park.

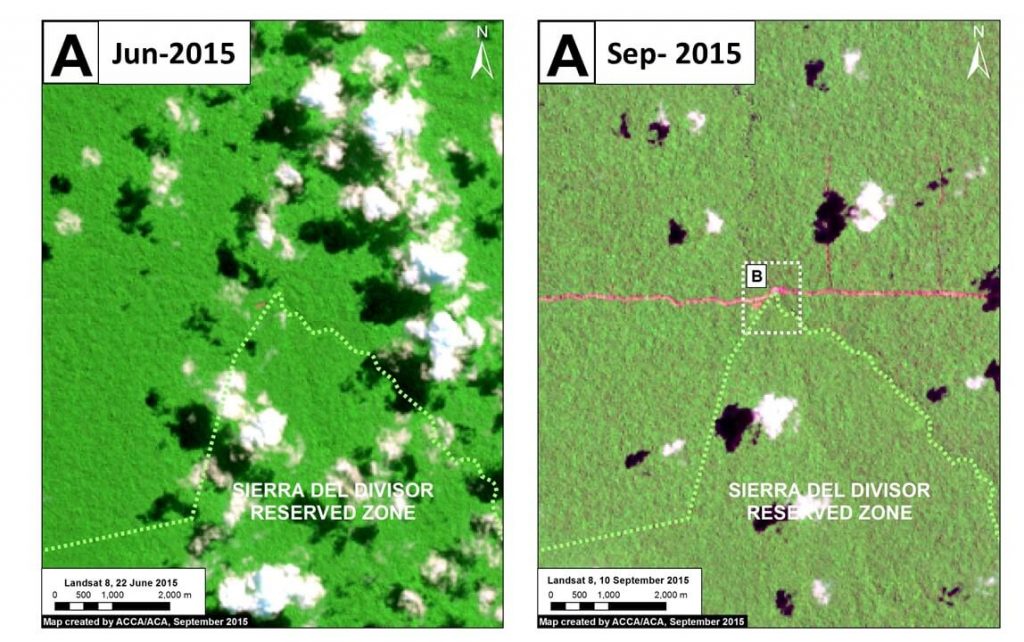

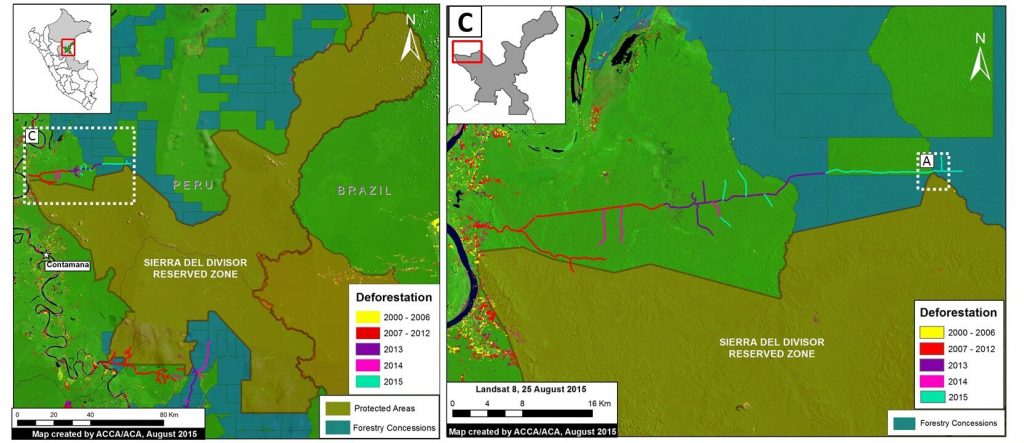

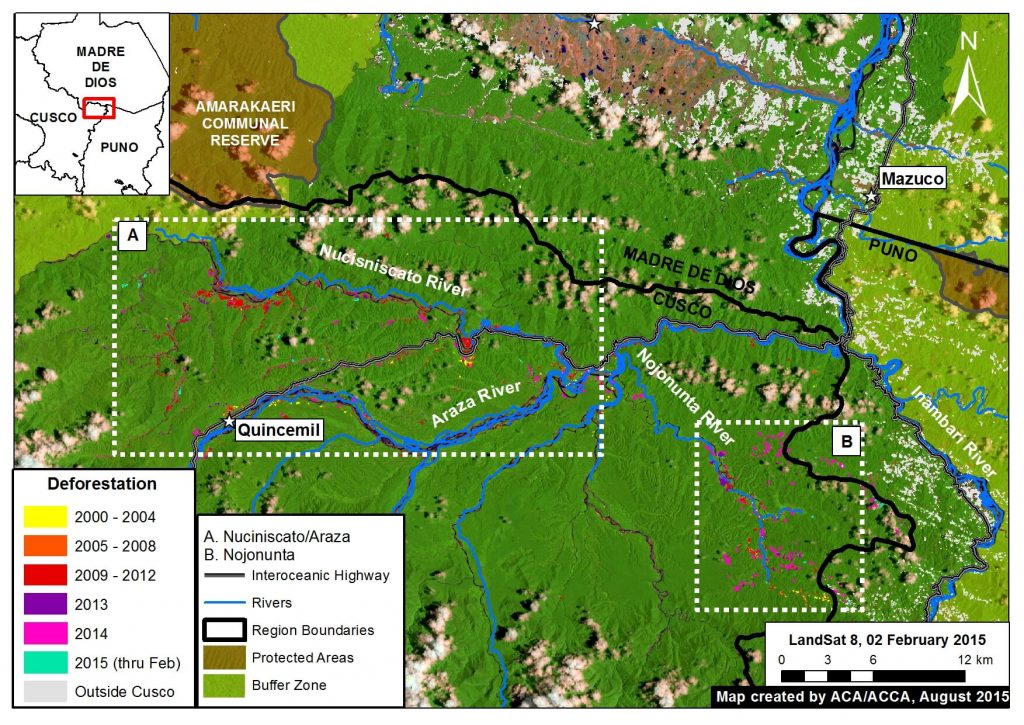

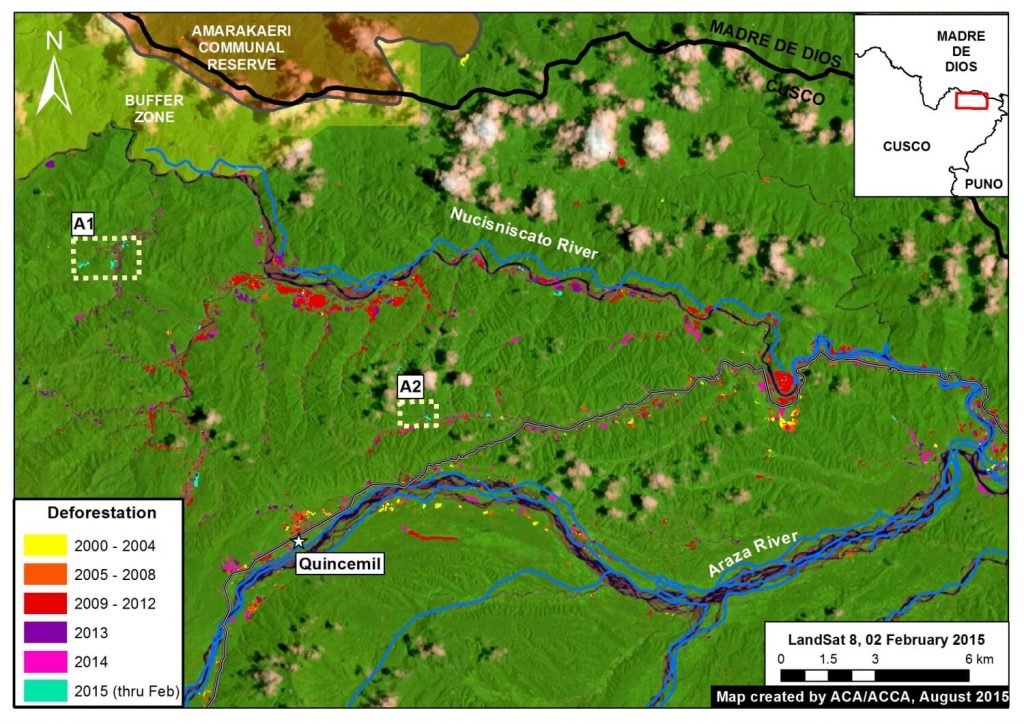

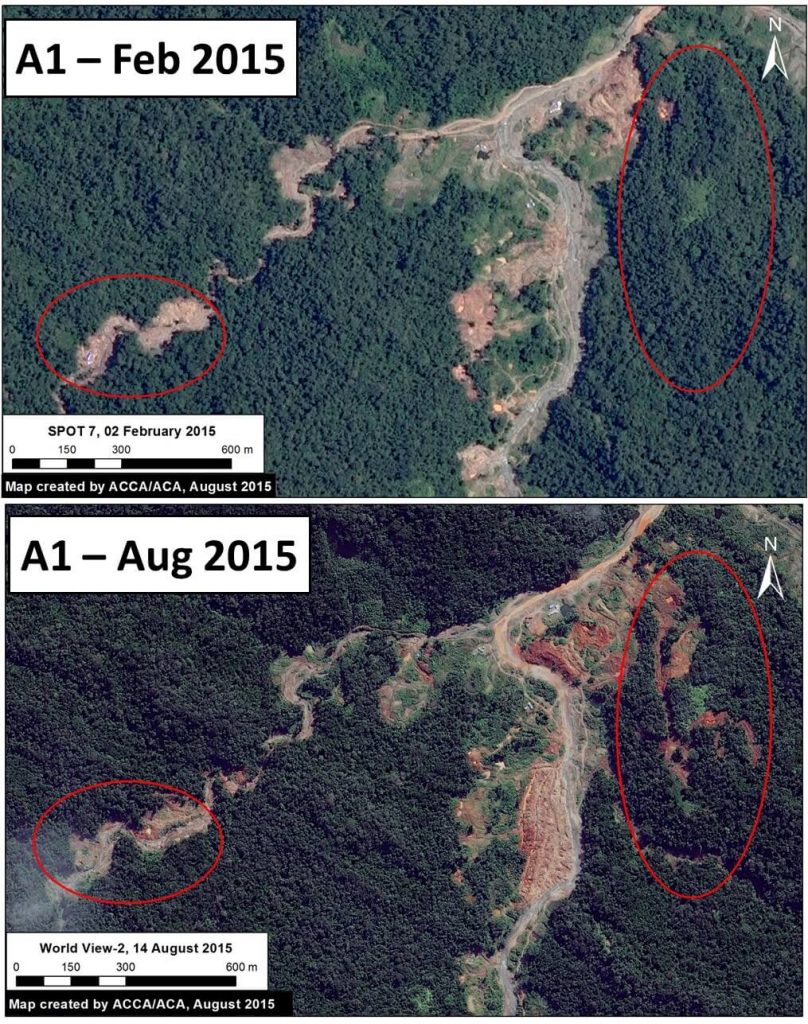

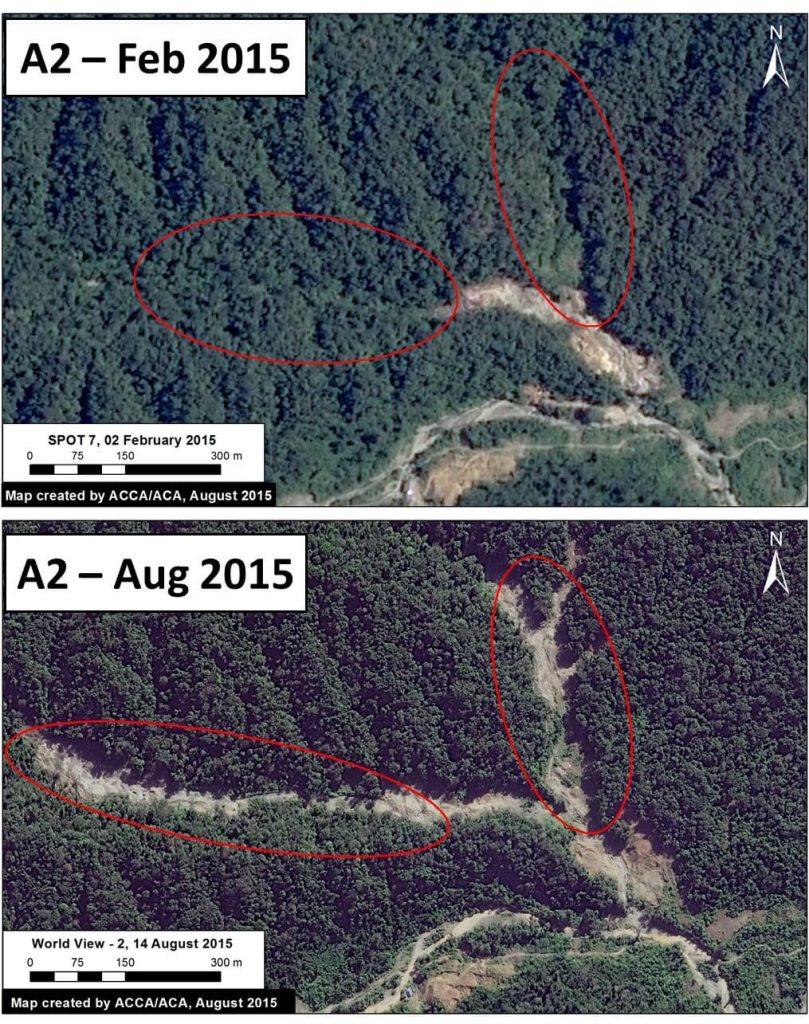

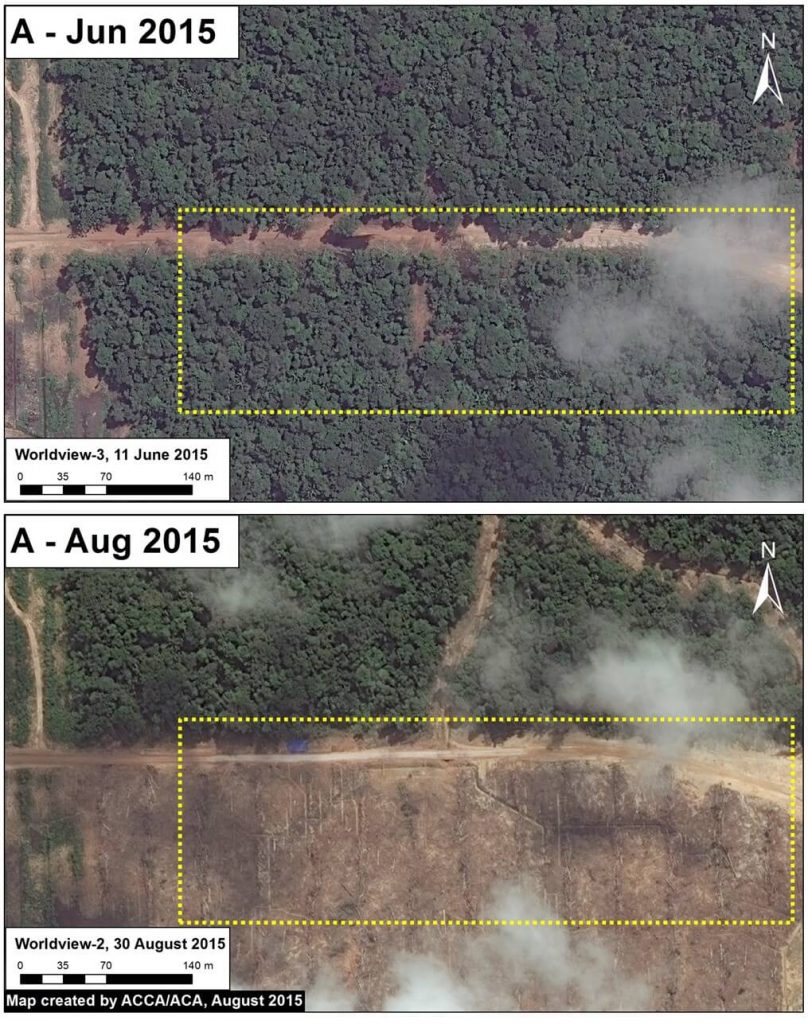

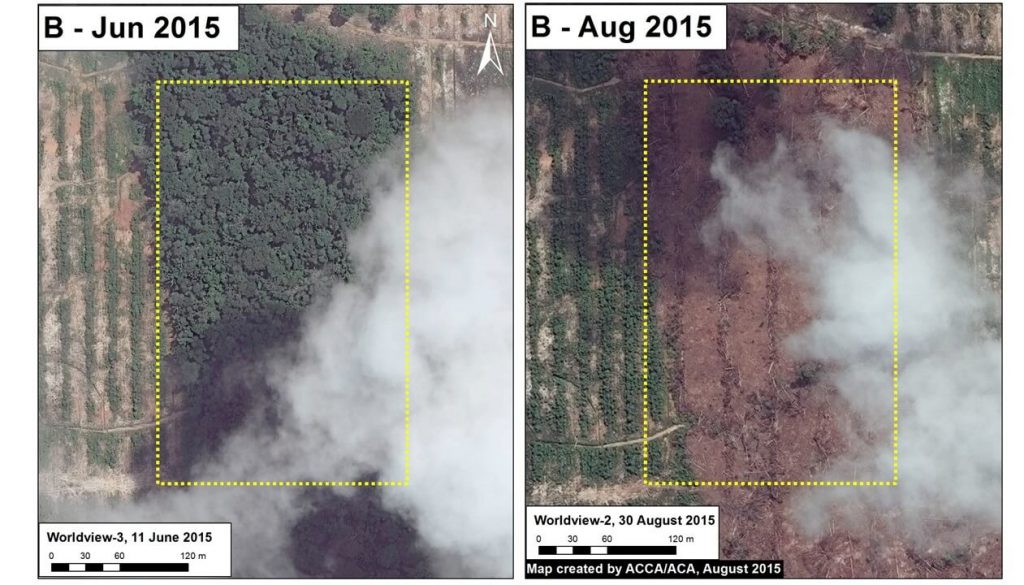

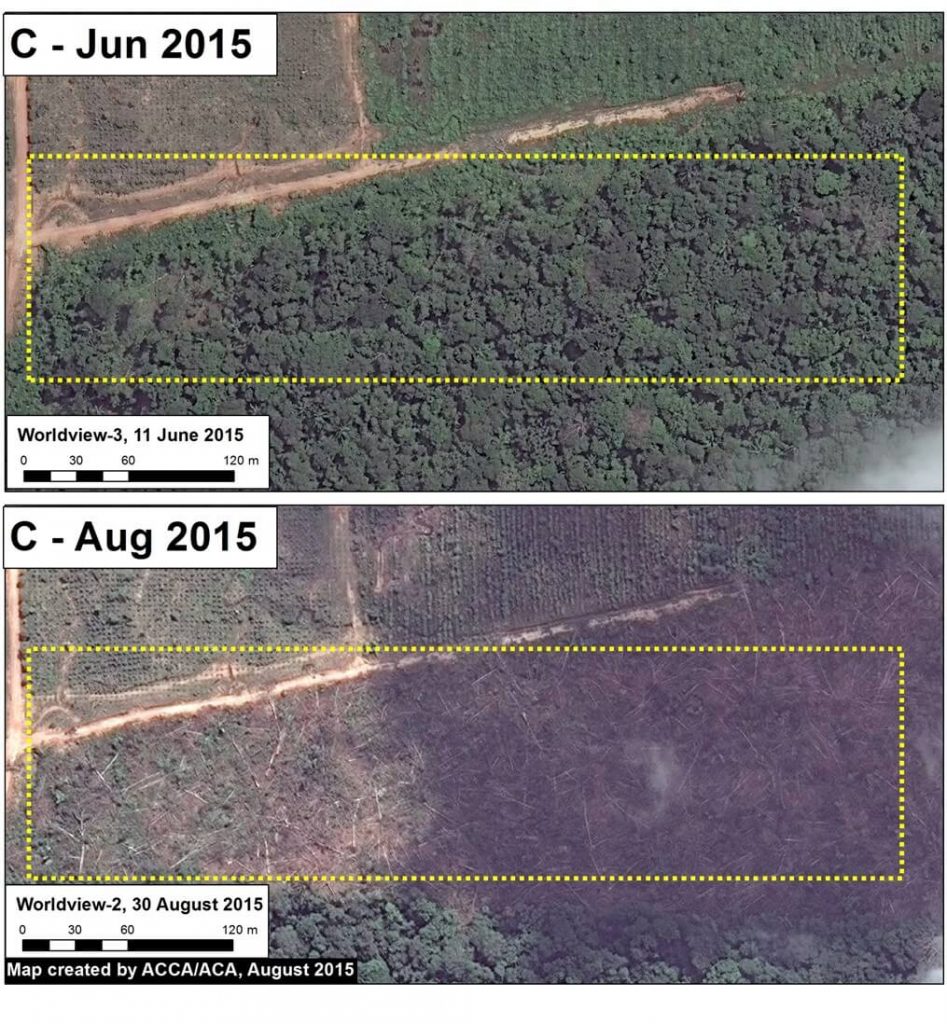

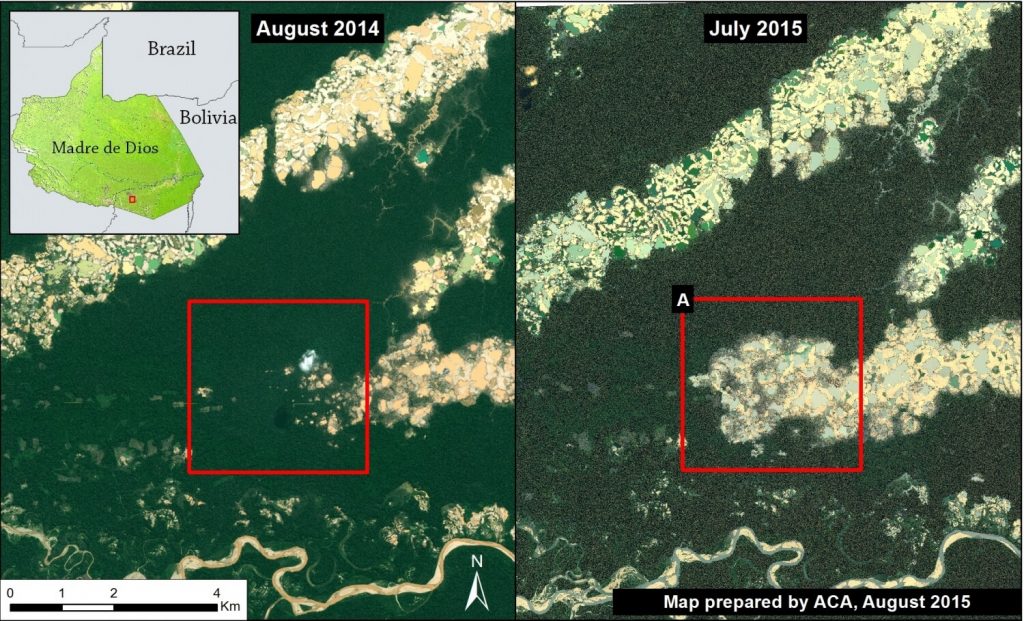

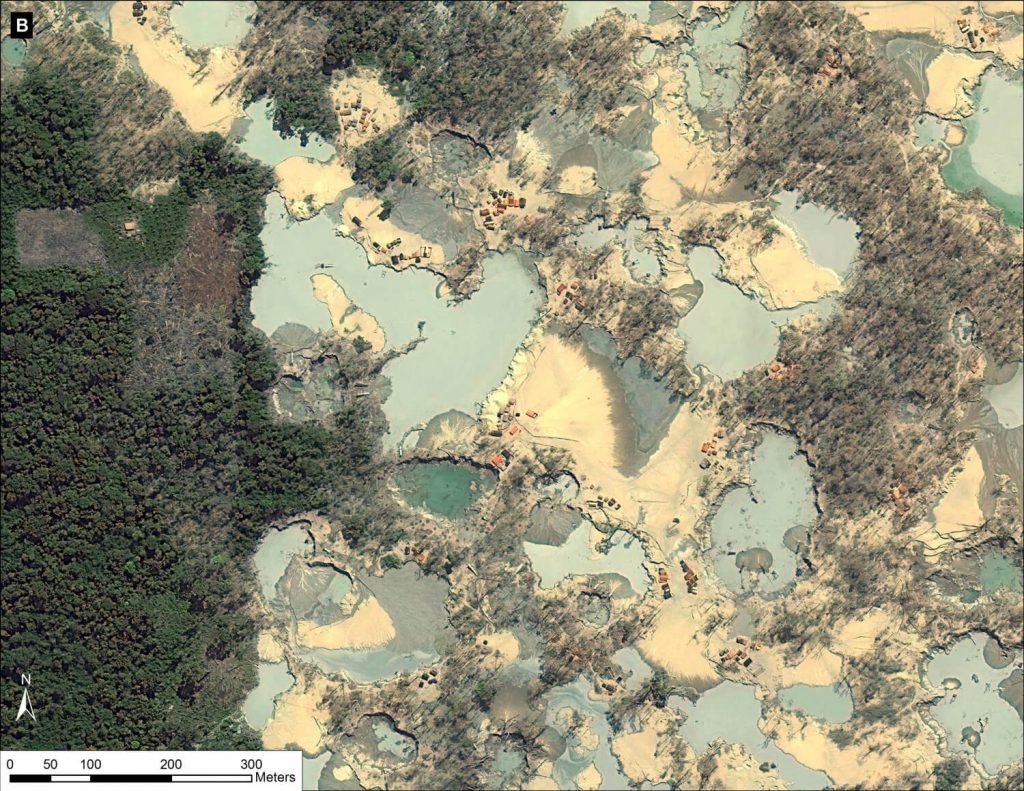

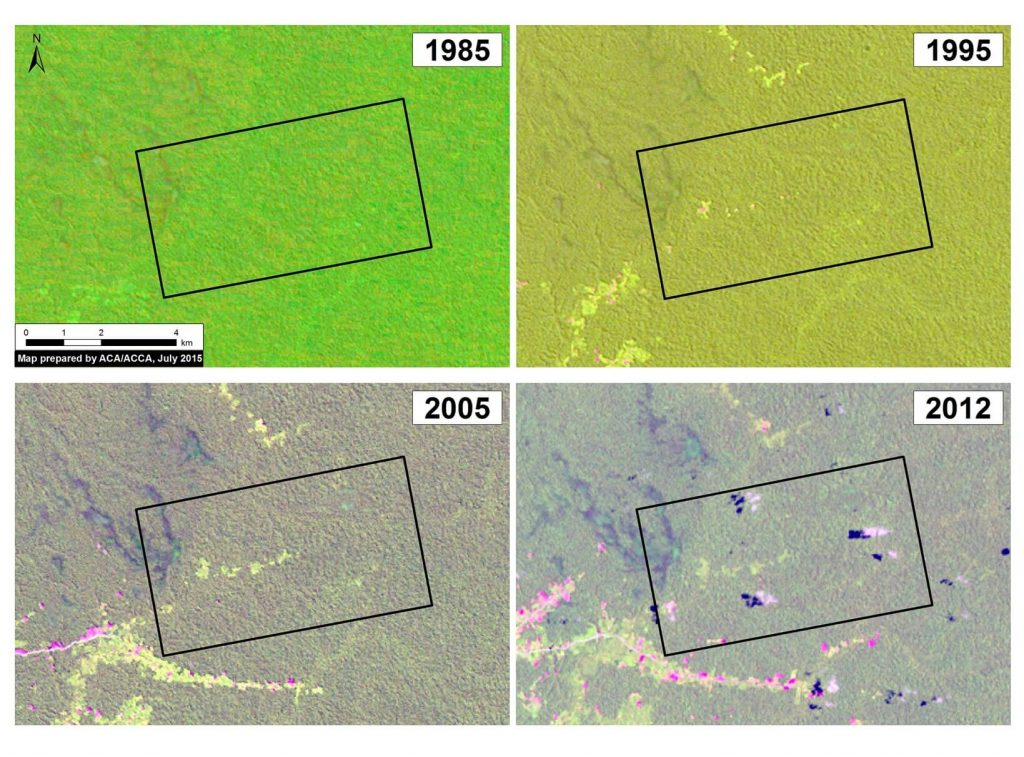

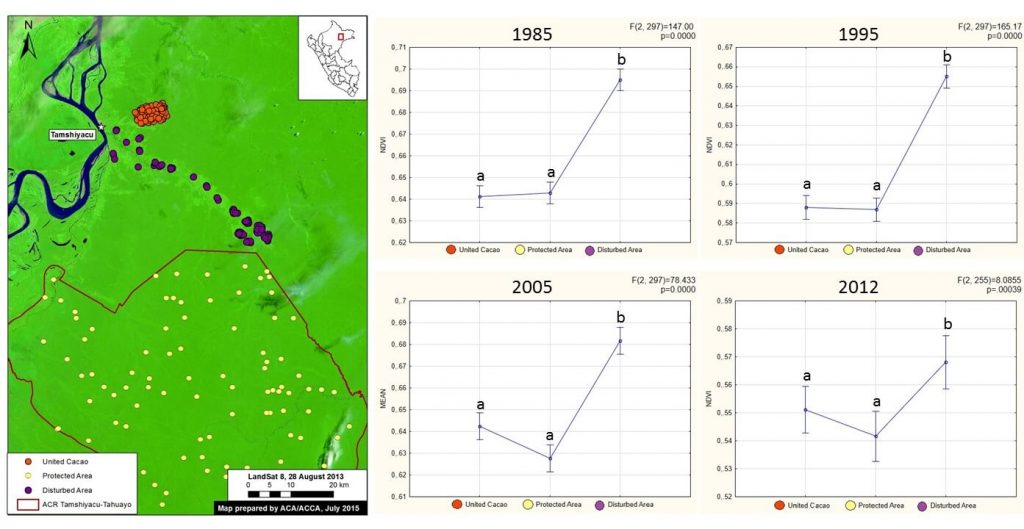

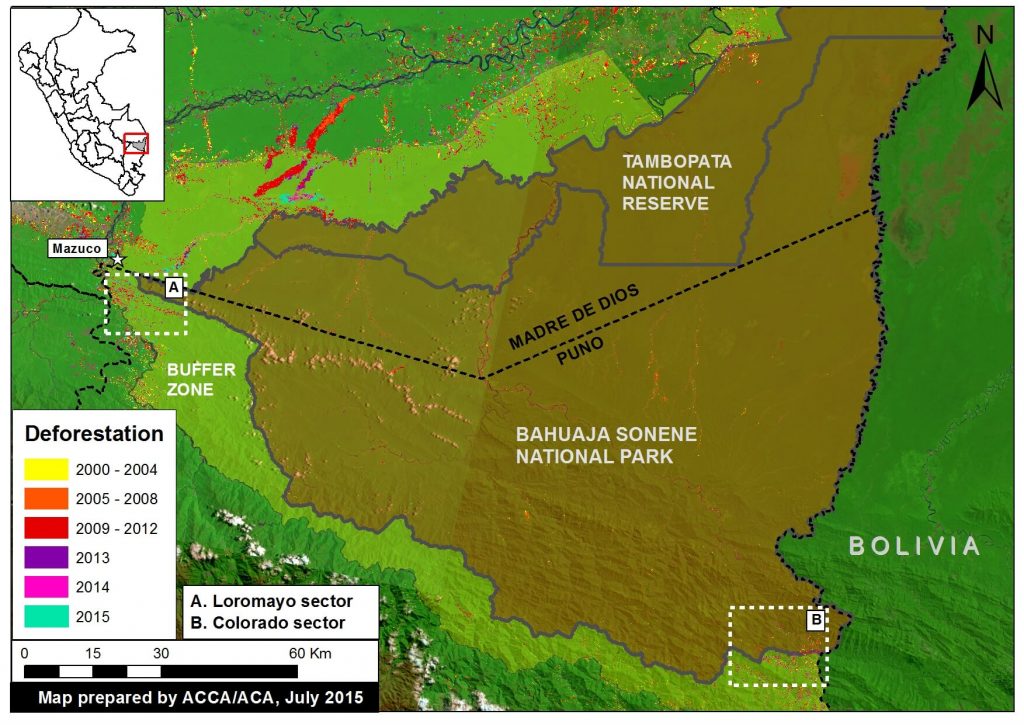

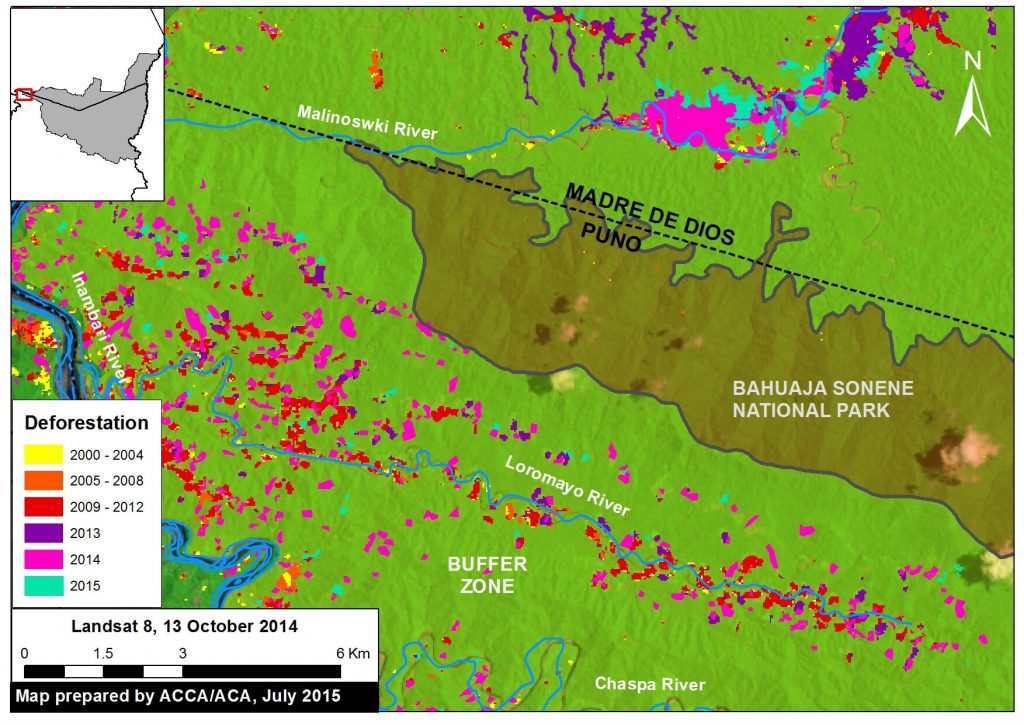

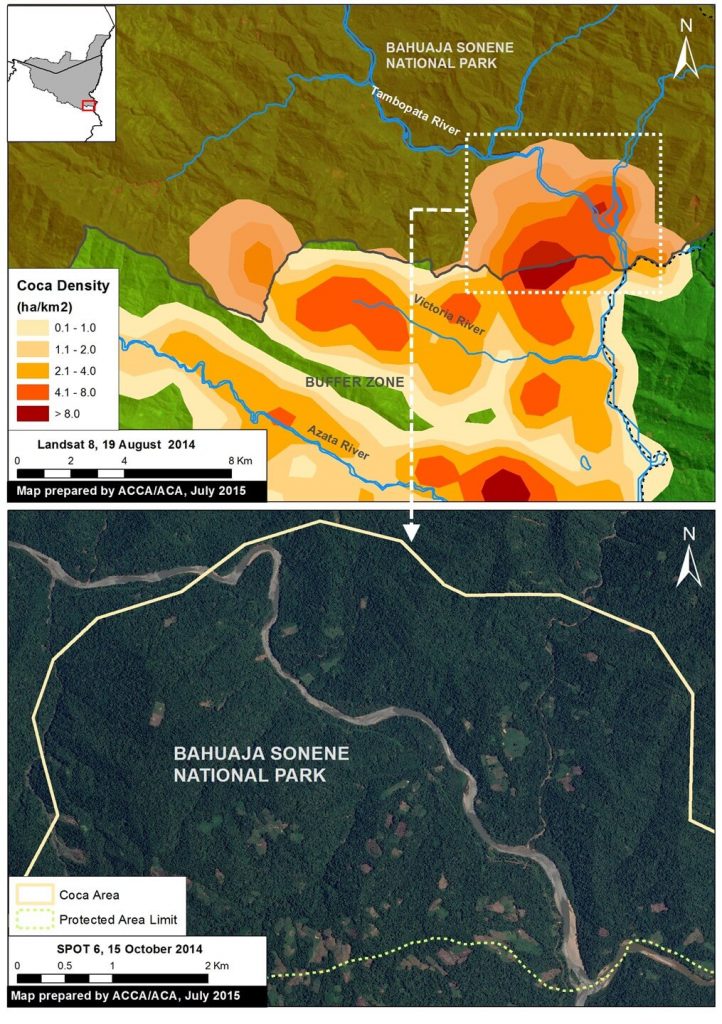

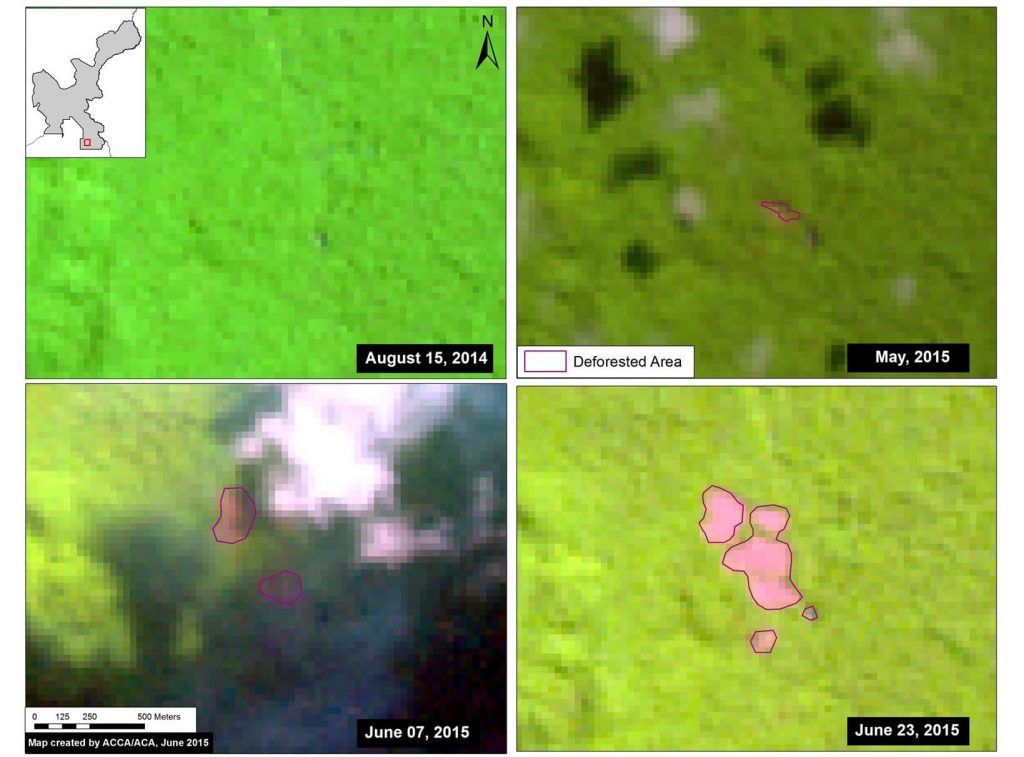

Image 15a shows the most recent expansion of the logging road between June (left panel) and September (right panel) 2015. For more context, note that the area displayed in Image 15a corresponds to the dashed box marked with the letter “A” in Image 15c.

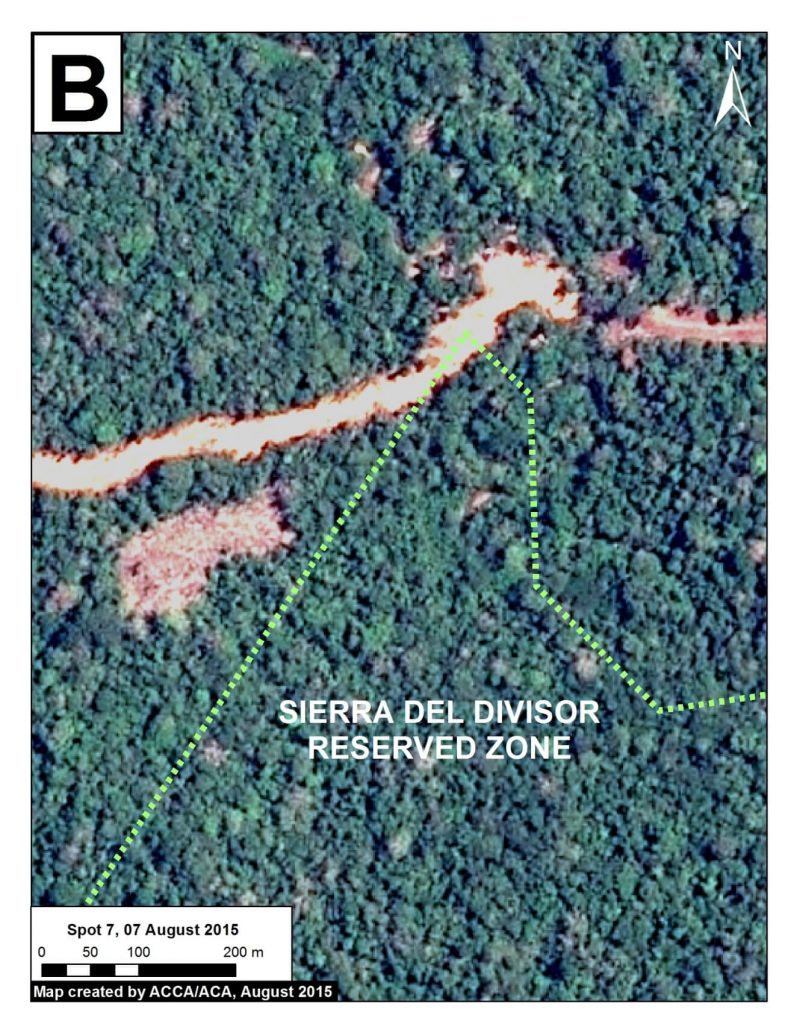

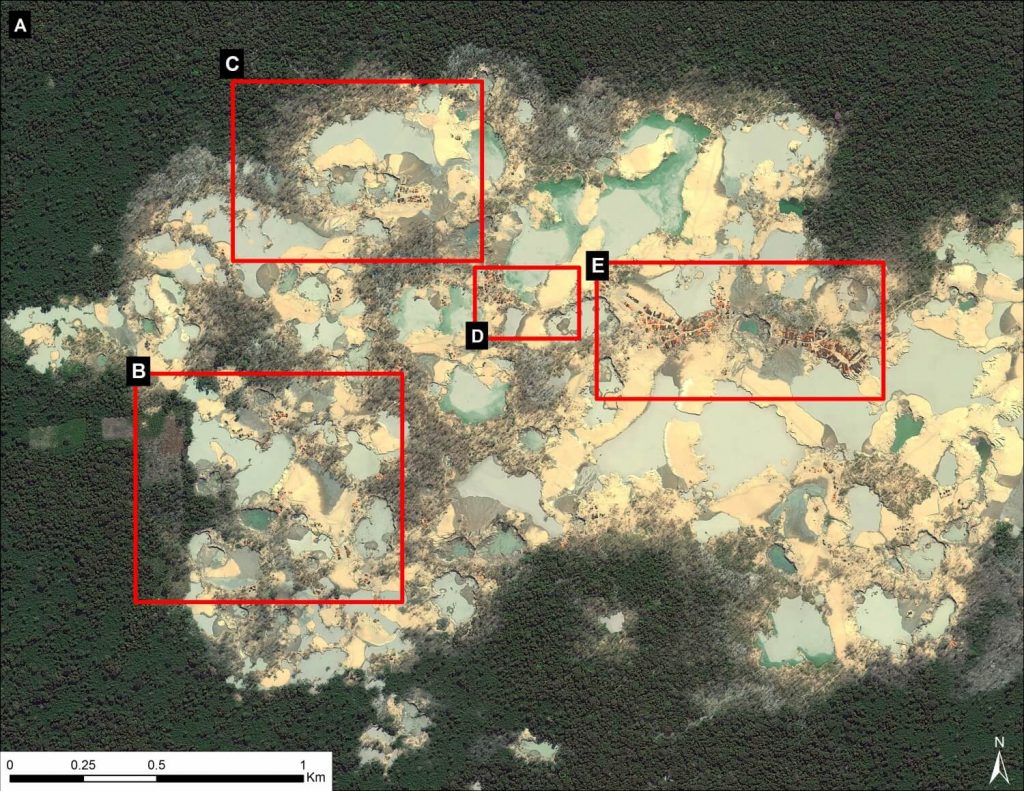

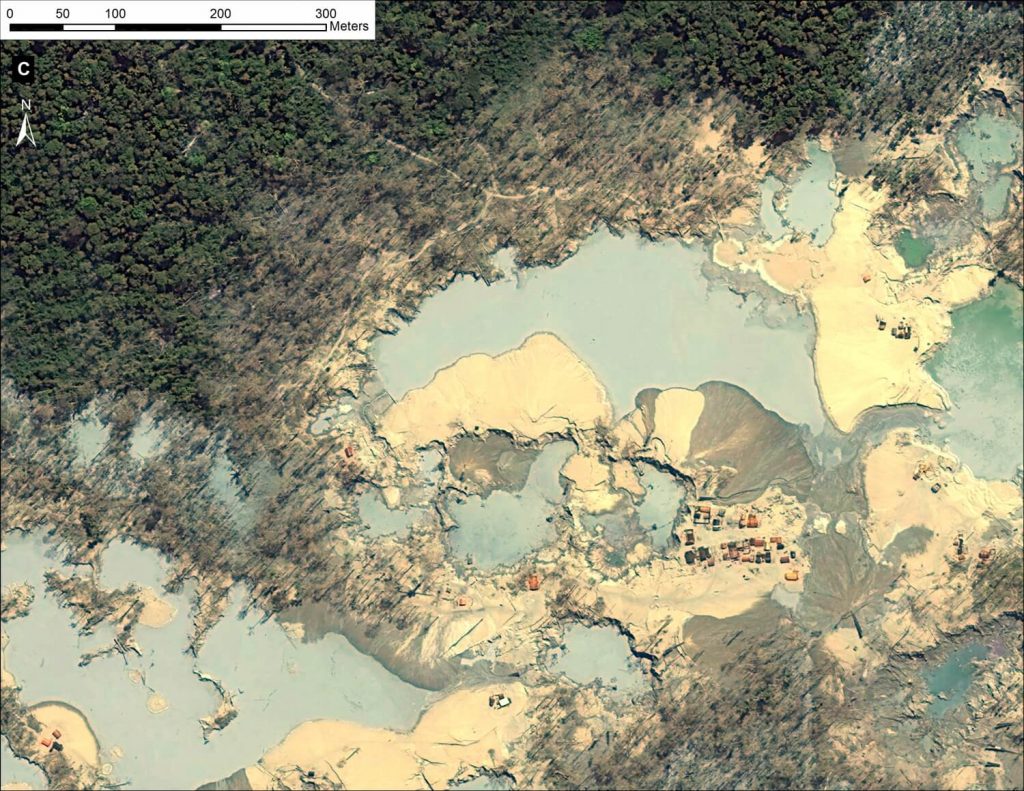

Image 15b displays a high-resolution (1.5 m) image from August 7 of the section of road crossing the northern section of the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone.

Expansion 2012 – 2015

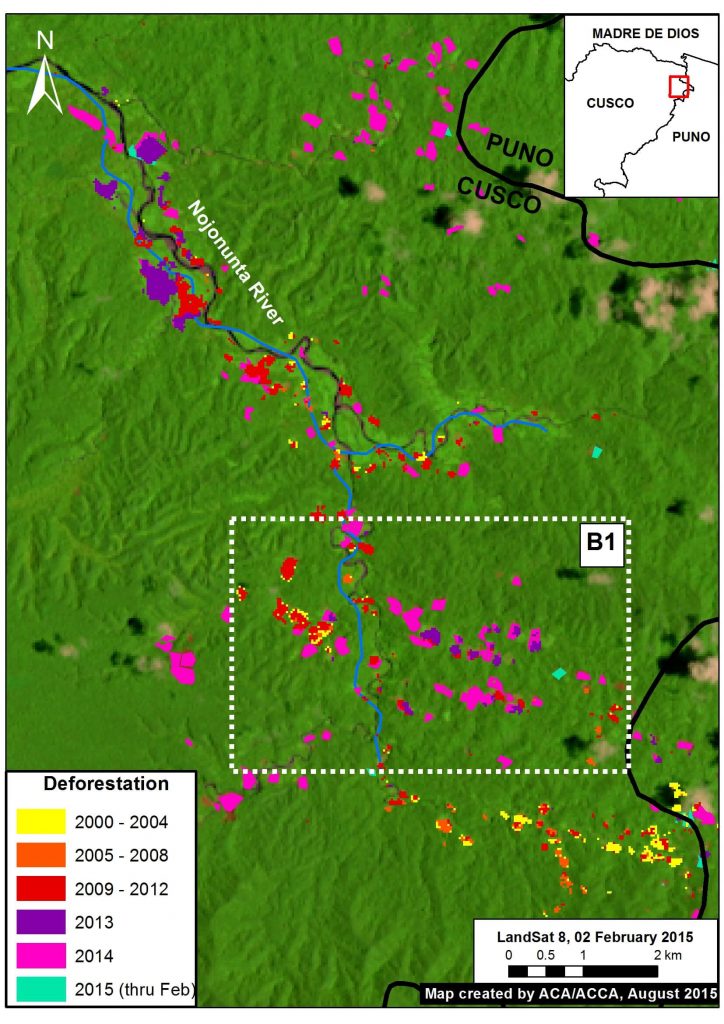

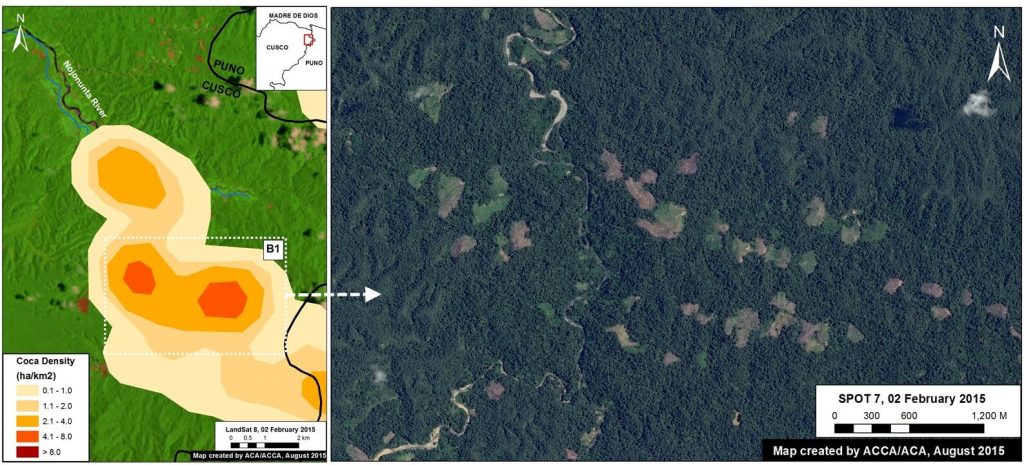

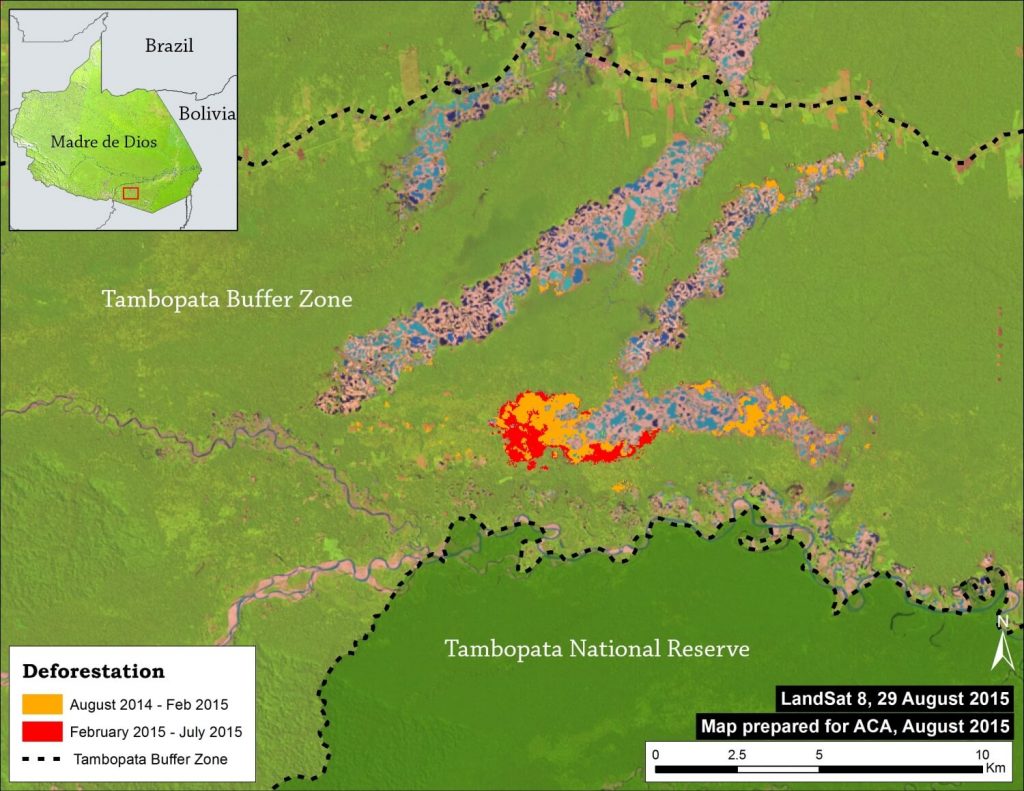

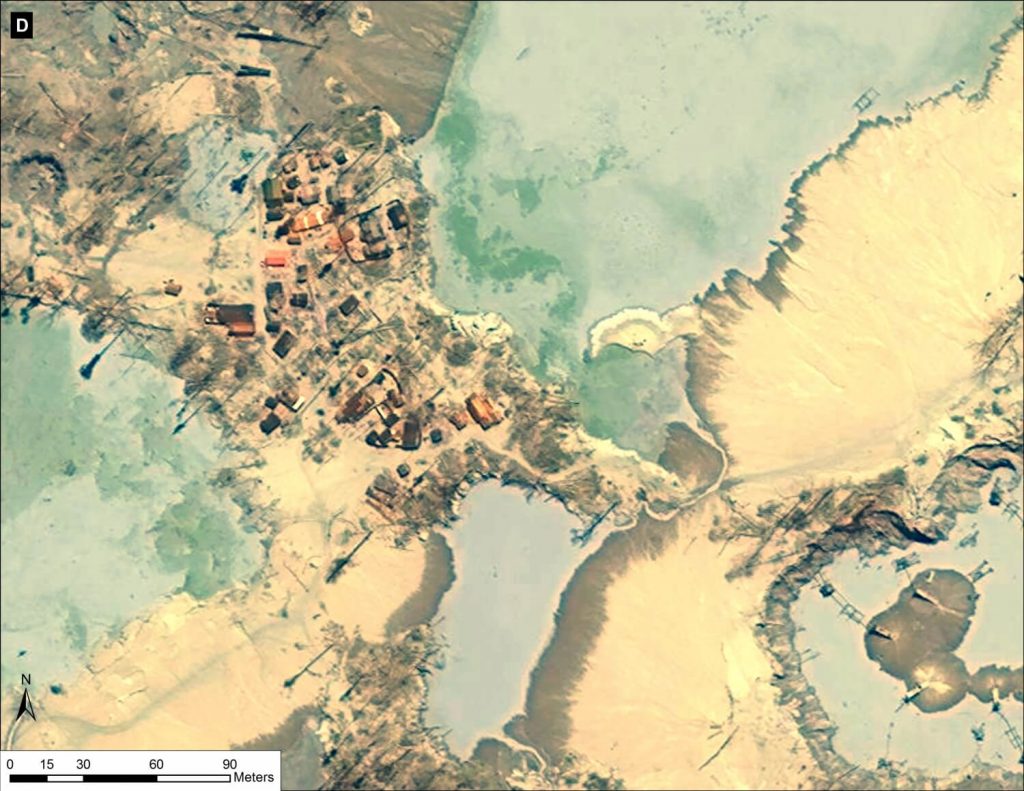

In Figure 15c, we show the expansion of this logging road from 2012 to 2015, totaling approximately 75 km of new road construction during these three years.

Carbon Data

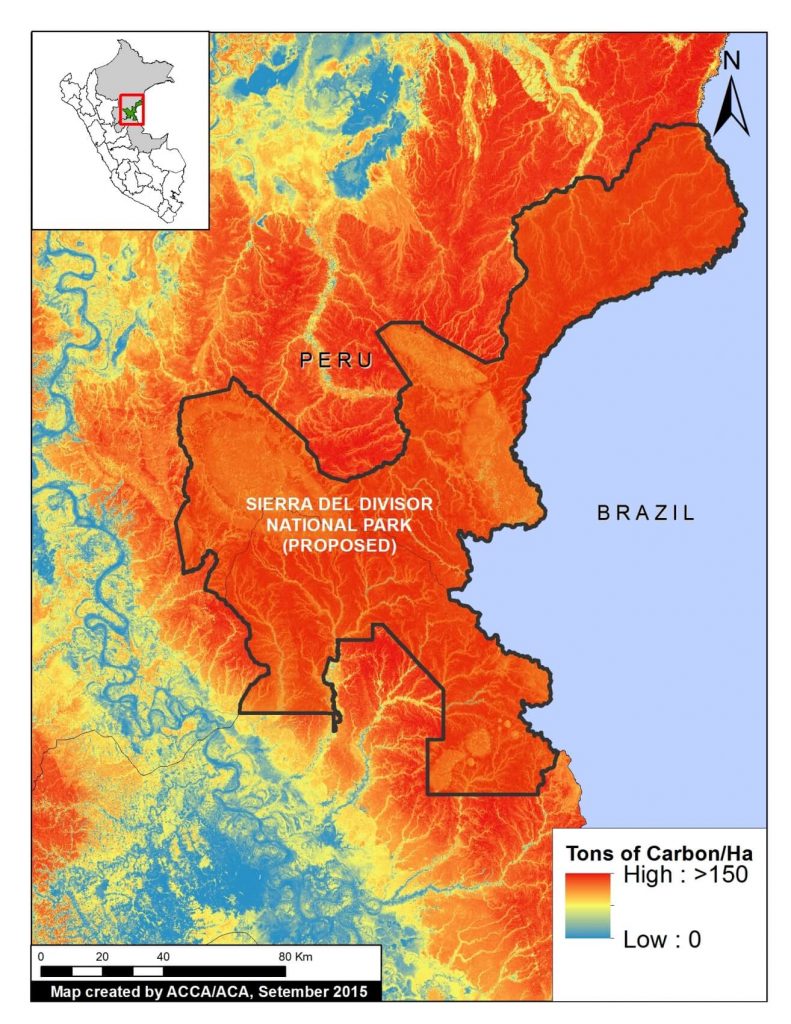

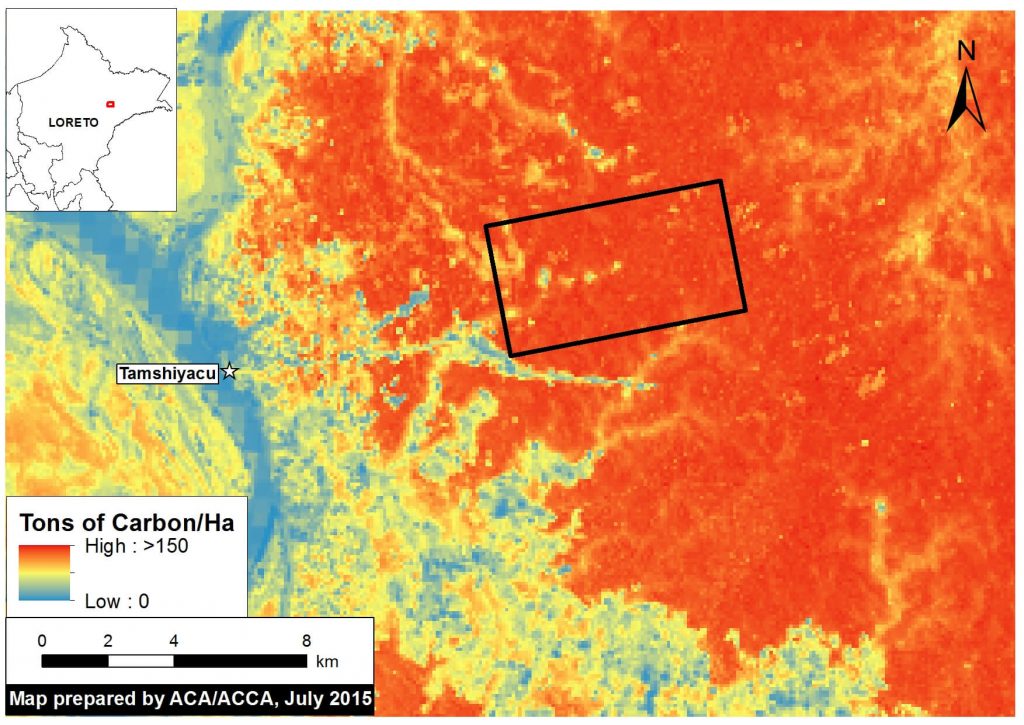

Dr. Greg Asner (from the Carnegie Institution for Science) and colleagues recently produced a high-resolution carbon map of Peru (Asner et al. 2014 a,b).

According to this data, the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone has the second largest carbon stock among all Peruvian protected areas (behind only Alto Purus National Park).

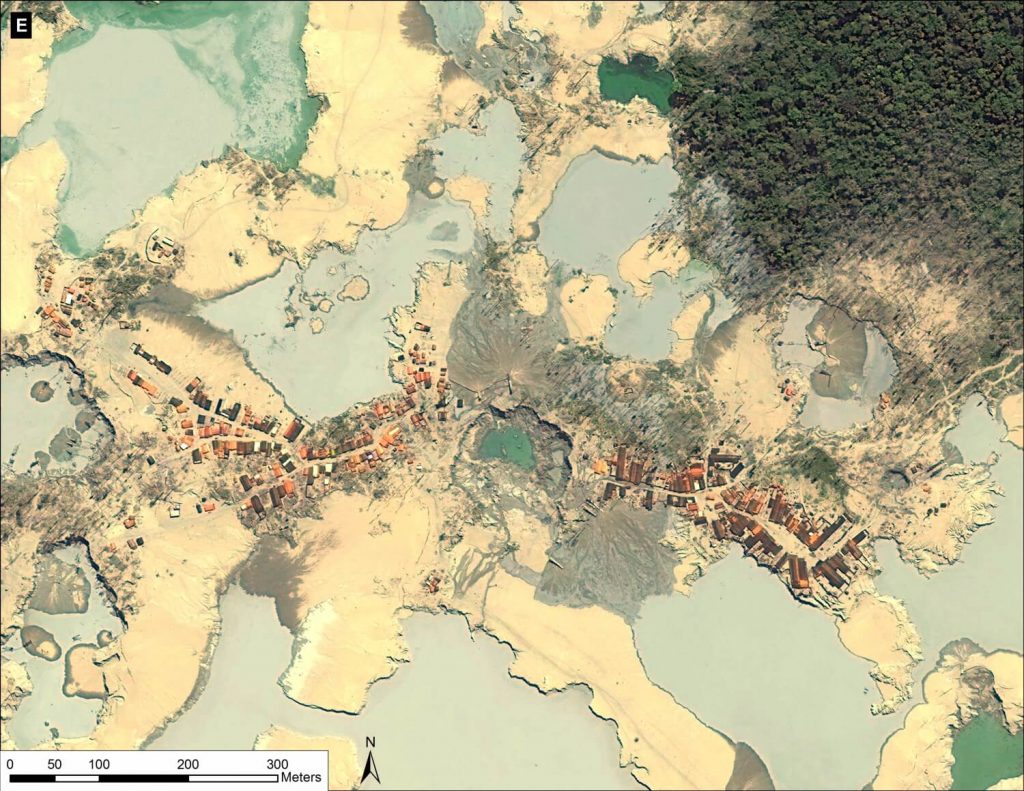

As seen in Image 15d, much of the proposed national park area contains high to very high carbon levels. Using this data, we calculated that the proposed Sierra del Divisor National Park contains approximately 165 million metric tons of above-ground carbon.

SERNANP Response

In response to this article, SERNANP (the Peruvian protected areas agency) issued this statement:

The deforestation alert in the northwest sector parallel to the Sierra del Divisor Reserved Zone is caused by the improvement of an alleged older road that runs along the natural protected area, which is being operateded by a neighboring forest concessionaire. We denounced this before the Special Prosecutor for Environmental Matters in Loreto in 2012, as we considered it irregular and a threat to the protected area.

[La deforestación que se advierte en el sector noroeste paralelo a la Zona Reservada Sierra del Divisor se origina por el mejoramiento de una supuesta carretera antigua que viene ejecutando un concesionario forestal colindante con el área natural protegida, la cual denunciamos ante la Fiscalía Especializada de Materia Ambiental – Loreto en el año 2012, por considerarla irregular y constituirse en una amenaza a este espacio protegido.] This past August, the Special Prosecutor scheduled an inspection, which was conducted jointly with the Public Prosecutor of the Ministry of the Environment. We have been making every effort to ensure that the Special Prosecutor performs the corresponding actions according to law, such as requiring OSINFOR to supervise the forest concessionaire due to the irregular events that we denounced. [Recién en agosto último la Fiscalía programó la inspección fiscal, que se realizó conjuntamente con la Procuraduría Pública del Ministerio del Ambiente, en la cual venimos realizando todos los esfuerzos para que la Fiscalía Especializada realice las actuaciones que corresponde de acuerdo a Ley, así como requerir al OSINFOR supervise al concesionario forestal, por los hechos irregulares que denunciamos.] Lima, 17 de setiembre del 2015References

Asner GP, Knapp DE, Martin RE, Tupayachi R, Anderson CB, et al. (2014 a) Targeted carbon conservation at national scales with high-resolution monitoring. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(47), E5016-E5022.

Asner GP, Knapp DE, Martin RE, Tupayachi R, Anderson CB, et al. (2014 b) The high-resolution carbon geography of Peru. Berkeley, CA: Minuteman Press.

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S (2015) Sierra del Divisor – New logging road crosses northern section of Reserve Zone MAAP: Image #15. Link: https://maaproject.org/2015/09/image15-sierra-divisor/

Loading...

Loading...