This International Women’s Day, we’re highlighting a powerful woman who has helped advance the protection of the Amazon for many years within various roles at Amazon Conservation. Amy Rosenthal, who has worked directly with the organization and now helps guide the institutional vision as one of our board members, is a longtime environmental advocate and has experienced firsthand the changes and challenges within the field of environmental protection.

This International Women’s Day, we’re highlighting a powerful woman who has helped advance the protection of the Amazon for many years within various roles at Amazon Conservation. Amy Rosenthal, who has worked directly with the organization and now helps guide the institutional vision as one of our board members, is a longtime environmental advocate and has experienced firsthand the changes and challenges within the field of environmental protection.

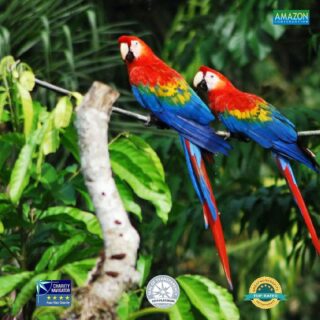

Amy’s interest in environmental conservation dates back to middle school, when she was doing science projects on the rainforest. She remembers showing her class, “old-school slides of pictures of the Amazon — the ones where you pop them into a round carousel.” Many years later, she finally had the opportunity to visit the Amazon in 2000. “To this day, I love the smell, the tastes, the colors, the element of surprise and wonder that’s with you everywhere in the Amazon. And I admire the people who know this place better than I ever will. They are the stewards and storytellers of the most magical place on our planet.”

During that trip, she remembers the majority of her mentors were men, as well as the researchers she worked with. “Things have changed a lot for women in fieldwork and conservation…As time went on, more of my colleagues were women, and I began to encounter more female mentors. Today, you’re more likely to run across women leaders in international fora and in our partner organizations and local community allies.” She believes that this change is due to a variety of drivers. “Early women leaders helped pave the way for others, as I found in my mentors; male mentors, like our founder, Adrian Forsyth, opened doors. More women were admitted to the sciences for their educational advancement, particularly in the fields of conservation science.” Additionally, Amy commends how the work of conservation has changed, to becoming deeply transdisciplinary, requiring project management and team-building, in addition to field biology. “All of these shifts seem to have brought in more women, which is wonderful to see and be a part of!”

Amy Rosenthal on a visit to our biological stations in 2007

Though there are more women now than ever working in the environmental field statistically, there is still progress to be made. In 2014, Dorceta E. Taylor published a report on the state of diversity in environmental organizations, finding that out of the 300 environmental institutions surveyed, men are still more likely than women to occupy the most powerful positions in environmental organizations. Additionally, there is still a low percentage of minorities on the boards of environmental organizations. Amy stresses the importance of diversity noting that, “Boards that have members from the same profession, socioeconomic background, or ethnicity are vulnerable to making poor decisions because they don’t reflect the diversity of thought, knowledge, and experience that the most important and difficult decisions require. An ideal board, which we’re working towards, would have members who can represent the worldviews, experiences, and local knowledge of the communities that Amazon Conservation works with. With that wisdom incorporated into our decision-making, we’ll be an even stronger board and the organization will have more meaningful, salient, and legitimate impact where we know the planet’s forests need it most.”

Photo by Amy Rosenthal

This all leads back to developing an efficient, effective, and holistic approach to strategically protecting the Amazon, which is a crucial wellspring for the world and for the local communities who live there. As one of the five great forests with significant biocultural diversity, there are still many species to discover that play a critical role in how ecosystems function. Amy notes that, “Fortunately, the world is more focused on protecting biodiversity and safeguarding our climate today than ever before…At the same time, there’s finally a recognition of the indispensable role Indigenous and local communities play in stewarding their lands, opening doors for direct support and nesting of traditional management and knowledge. And today’s technology gets us closer to real-time global biodiversity monitoring and conservation than ever before.” She concludes that, “Amazon Conservation is a pathbreaking leader in many of these spheres, informing policies, harnessing hi-tech solutions, and partnering with Indigenous organizations to ensure durable, holistic and equitable conservation of the Amazon. I am proud and honored to be a part of it!”

This year, Earth Day celebrates all the incredible resources that this beautiful planet provides us. We are taking Earth Day a few steps furtherand celebrating the greatest wild forest on the planet for the entire month of April! We encourage everyone to start taking action for nature and the Amazon this April, but we hope this will be just the start as our planet needs real impactful and urgent action each and every day.

This year, Earth Day celebrates all the incredible resources that this beautiful planet provides us. We are taking Earth Day a few steps furtherand celebrating the greatest wild forest on the planet for the entire month of April! We encourage everyone to start taking action for nature and the Amazon this April, but we hope this will be just the start as our planet needs real impactful and urgent action each and every day.

This International Women’s Day, we’re highlighting a powerful woman who has helped advance the protection of the Amazon for many years within various roles at Amazon Conservation. Amy Rosenthal, who has worked directly with the organization and now helps guide the institutional vision as one of our

This International Women’s Day, we’re highlighting a powerful woman who has helped advance the protection of the Amazon for many years within various roles at Amazon Conservation. Amy Rosenthal, who has worked directly with the organization and now helps guide the institutional vision as one of our

Loading...

Loading...