This past Wednesday saw the fourth installment of the AmazonTEC virtual conference, Technology, Climate and the Future of the Amazon, where participants discovered how climate and carbon affect the greatest rainforest on the planet. Ahead of the UN Climate Conference (COP26), our panel of environmental experts focused on three relevant areas: climate and carbon, their effect on species, and impact on local peoples. Speakers revealed whether the Amazon was moving from carbon sink to a carbon source, how protected areas and indigenous territories are key measures for combating climate change, and the climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience measures that could be created to create a stronger Amazon. Watch the full English language sesion here.

This past Wednesday saw the fourth installment of the AmazonTEC virtual conference, Technology, Climate and the Future of the Amazon, where participants discovered how climate and carbon affect the greatest rainforest on the planet. Ahead of the UN Climate Conference (COP26), our panel of environmental experts focused on three relevant areas: climate and carbon, their effect on species, and impact on local peoples. Speakers revealed whether the Amazon was moving from carbon sink to a carbon source, how protected areas and indigenous territories are key measures for combating climate change, and the climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience measures that could be created to create a stronger Amazon. Watch the full English language sesion here.

Renowned Brazilian scientist and meteorologist Carlos Nobre opened the session with cautionary warnings against the “tipping point” of the Amazon, where so much of the rainforest is deforested that the Amazon can no longer generate its own rainfall and subsequently turns into a savanna. Nobre has done extensive research around this concept as well as coined the term, warning that, “The risk [of reaching the tipping point] is very serious because we are already seeing this in areas of the Amazon, mostly in the southeastern Brazilian Amazon. Many studies are showing that in this region the forests have already become a carbon source [due to the extensive deforestation].”

Manuel Pulgar Vidal, who moderated the session, added that, “When we think about climate, we are talking about the big challenges that we have in front of us…We have to continue developing our actions to adapt and be well adapted to the new reality of the Amazon. We have some nature-based solutions despite political resistance.” He then introduced the first panel presentations, which were about what science and technology are saying about carbon and climate in the Amazon.

Climate And Carbon

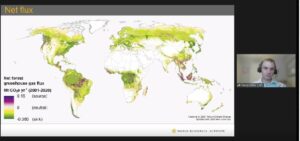

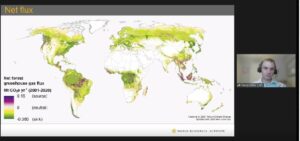

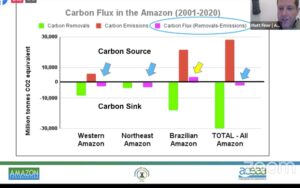

During the first section, “Climate and Carbon”, David Gibbs, a GIS Research Associate in Global Forest Watch at World Resources Institute, presented a global overview on carbon flux, which describes the exchange of carbon between different carbon reservoirs. The carbon flux maps he showed were created by researchers around the world and will be updated over time. “We have already updated our map once, we will update it again to include

During the first section, “Climate and Carbon”, David Gibbs, a GIS Research Associate in Global Forest Watch at World Resources Institute, presented a global overview on carbon flux, which describes the exchange of carbon between different carbon reservoirs. The carbon flux maps he showed were created by researchers around the world and will be updated over time. “We have already updated our map once, we will update it again to include  emissions. This is a living model, a living map.” He also noted the importance of global forests as carbon sinks, pointing out, “According to these maps, forests are net carbon sinks. They capture about twice as much carbon globally than they emit.”

emissions. This is a living model, a living map.” He also noted the importance of global forests as carbon sinks, pointing out, “According to these maps, forests are net carbon sinks. They capture about twice as much carbon globally than they emit.”

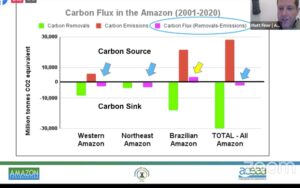

Matt Finer, our Director of the Monitoring of the Amazon Project, zoomed into the Amazon to present a regional perspective. “A bit of a shocking finding is that the Brazilian Amazon has flipped to becoming a carbon source, but the good news is that the Amazon as a whole is a carbon sink.” He emphasized that this is due to protected areas and indigenous territories in the Andean Amazon region, saying that, “They are very strong carbon sinks…all of the areas outside of these designations are a strong carbon source.”

Climate Impact on Species

Climate Impact on Species

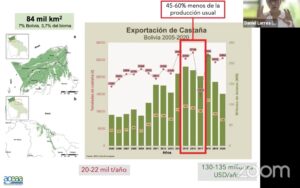

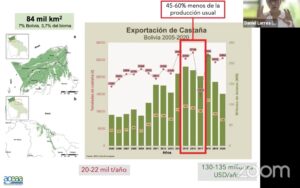

The second section focused on the climate impact on ecosystems, species and people. Daniel Larrea, Science and Technology Program Coordinator at Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA focused on the Brazil nut tree as a key method for conservation. “We have to take into account climate change and its effects and impacts on key forest products like Brazil nuts, which in turn impact local communities. I would like to share a quote…’Before being free it’s necessary to be fair,’ and I think that is something we can apply to nature.”

Climate, Carbon and Local People

The final two panelists presented about the relationship between climate, carbon and local people. Marcos Terán, the Executive Director of Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA explained that Brazil nuts are key to the conservation of Amazonian forests in Bolivia due to the value they give to standing forests. Harvesting naturally growing Brazil nuts provides an economic alternative to local populations that otherwise may choose to deforest the area and turn it into a monoculture. “In terms of Bolivia, we have an increased interest in Brazil nuts, açaí, and other native palms that can be used to strengthen communities’ livelihoods,” he explains. “And when you have a key resource like the Brazil nut, it values standing forest & gives local

The final two panelists presented about the relationship between climate, carbon and local people. Marcos Terán, the Executive Director of Conservación Amazónica – ACEAA explained that Brazil nuts are key to the conservation of Amazonian forests in Bolivia due to the value they give to standing forests. Harvesting naturally growing Brazil nuts provides an economic alternative to local populations that otherwise may choose to deforest the area and turn it into a monoculture. “In terms of Bolivia, we have an increased interest in Brazil nuts, açaí, and other native palms that can be used to strengthen communities’ livelihoods,” he explains. “And when you have a key resource like the Brazil nut, it values standing forest & gives local  populations an alternate way to generate income…Standing forest is worth more than the alternative.”

populations an alternate way to generate income…Standing forest is worth more than the alternative.”

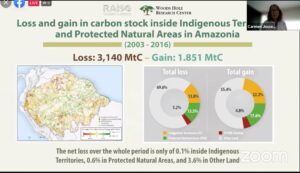

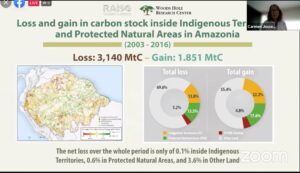

The final presenter was Carmen Josse, the Executive Director of the Ecuadorian nonprofit EcoCiencia, who provided a comprehensive overview of the distribution of carbon stored aboveground inside and outside the nine-nation network of Amazon indigenous territories and protected areas. She noted, “Amazonian indigenous territories & protected areas store over half of the region’s above ground carbon (58%)…The carbon net loss over 2003-2016 in these areas is only 0.1% inside indigenous territories, 0.6% in protected areas & 3.6% in other land.”

Question and Answer Session

Following the presentations was a question and answer session. One audience member asked Matt Finer, “How effective are indigenous territories & protected areas across the Amazon?” He referenced the findings from a recent MAAP report. “I think the data points to two major keys: maintaining and strengthening protected areas and indigenous territories. That’s where the big movement for the future will be to safeguard more land.”

Carlos Nobre was asked, “What type of global climate action is needed to avoid the ‘tipping point’?,” to which he replied, “Basically we are saying there has to be a moratorium, zero deforestation, zero degradation, zero fires in the Amazon. There needs to be a global movement led by the Amazonian countries.”

To view the full question and answer session and watch the entire presentation, click here.

Since she was 7 years old, Juliana has been accompanying her father in patrolling their forest for illegal deforestation as part of a community patrol program. She also spends mornings and evenings from July to October supplying collected rainwater to drinking areas that blue-throated macaws can access during Bolivia’s harsh dry season, when water is scarce. “Blue-throated macaws are wonderful,” she describes, “When I fill the water, they’ll sit and watch me, and when I’m alone sometimes I’ll talk to them…I feel content to help in this way.”

Since she was 7 years old, Juliana has been accompanying her father in patrolling their forest for illegal deforestation as part of a community patrol program. She also spends mornings and evenings from July to October supplying collected rainwater to drinking areas that blue-throated macaws can access during Bolivia’s harsh dry season, when water is scarce. “Blue-throated macaws are wonderful,” she describes, “When I fill the water, they’ll sit and watch me, and when I’m alone sometimes I’ll talk to them…I feel content to help in this way.”

Loading...

Loading...