Peru’s intense 2016 fire season continues, most recently hitting the northern part of the country.

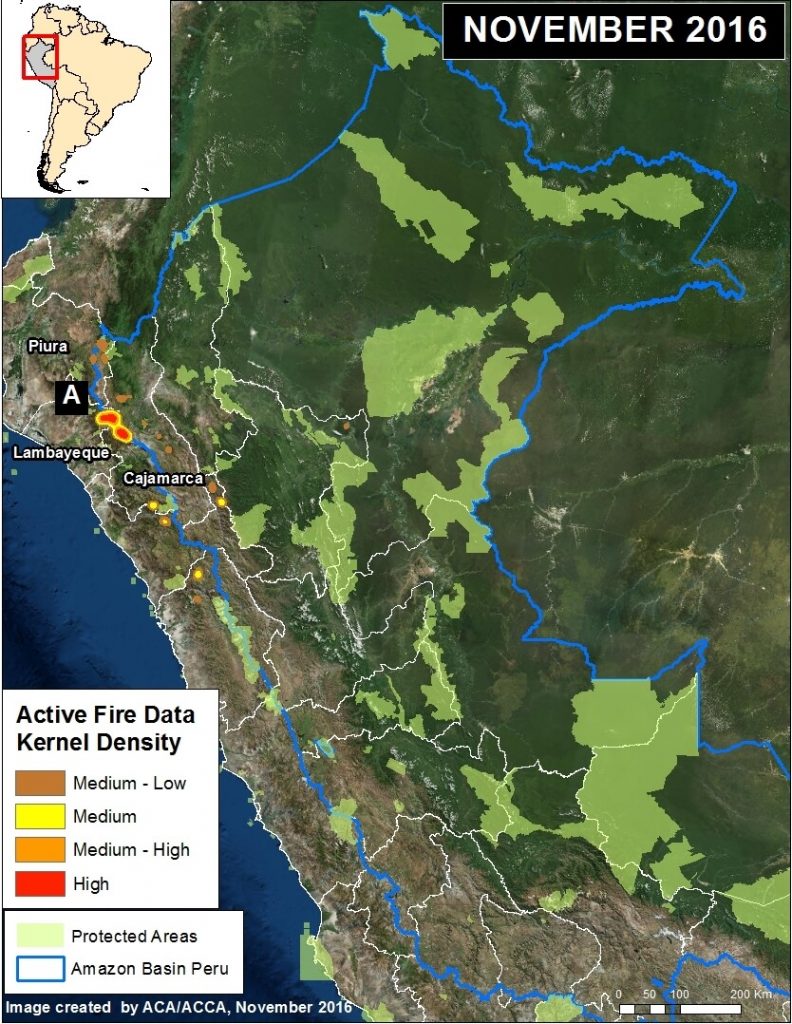

As seen in this map on the left, during November 2016 the highest concentration of fire alerts (as detected by the VIIRS satellite sensor) were concentrated in the headwaters of the northern Amazon basin (departments of Cajamarca, Piura, and Lambayeque).

It appears that the primary cause of these fires is poor agricultural burning practices during a time of intense drought. These conditions allowed fires to escape into protected areas, including 6 national-level protected areas and 1 municipal protected area.

Until additional cloud-free satellite images are available it is difficult to quantify the total burned area. However, by analyzing the currently available imagery, we estimate 1,980 acres burned in 3 of the protected areas (Laquipampa Wildlife Refuge, Chicuate-Chinguelas PCA, and Cachiaco-San Pablo PCA). The Peruvian protected areas agency, SERNANP, estimates an additional 1,000 acres burned in the Pagaibamba Protected Forest. In addition, by analyzing fire alert data, we estimate that an additional 890 acres affected in the other 3 protected areas (Cutervo National Park, Tabaconas Namballe National Sanctuary, and Huaricancha PCA. See below for details.

Moreover, the Peruvian civil society organization SPDA is highlighting that one of the main problems is the lack of fire-related planning by the Peruvian government, which since 2001 has not fulfilled its mandate to create a National System of Fire Prevention and Control.

Loading...

Loading...