Drone types- helicopter and fixed-wing (plane)

For the past three years, the organization Amazon Conservation has been working to establish a sustainable, local-based drones program for environmental monitoring in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region).

This program is based on two types of drones, multi-rotor (helicopter style) and fixed-wing (airplane style).

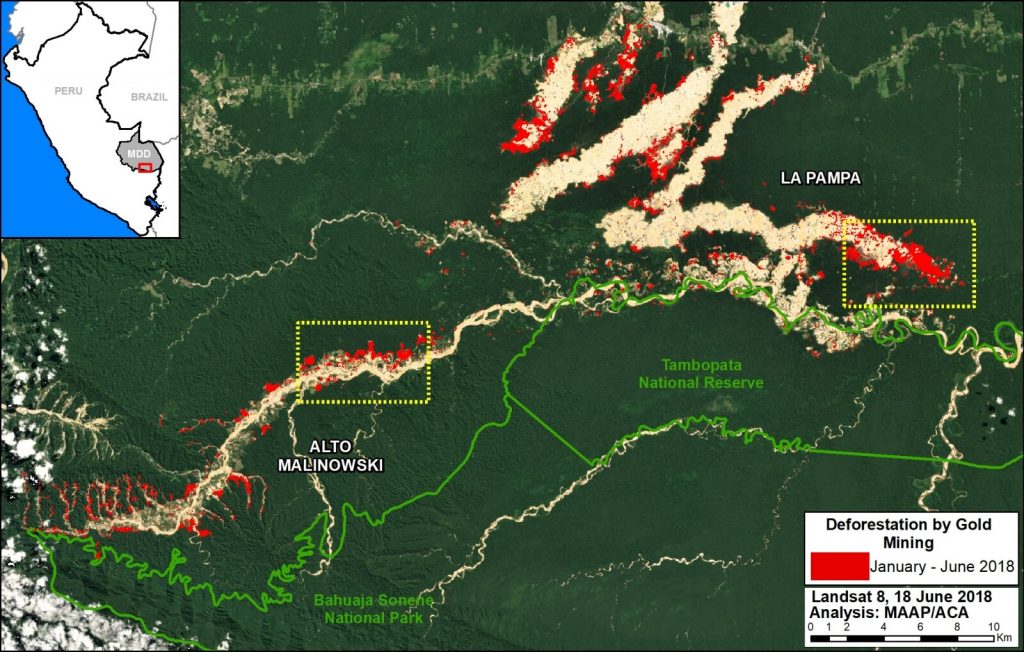

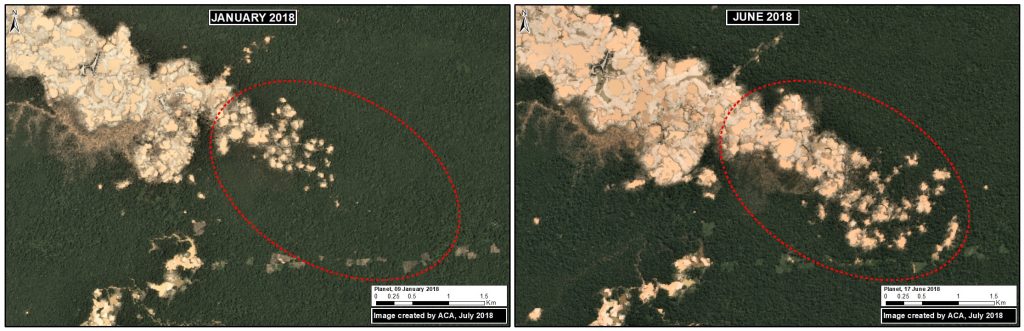

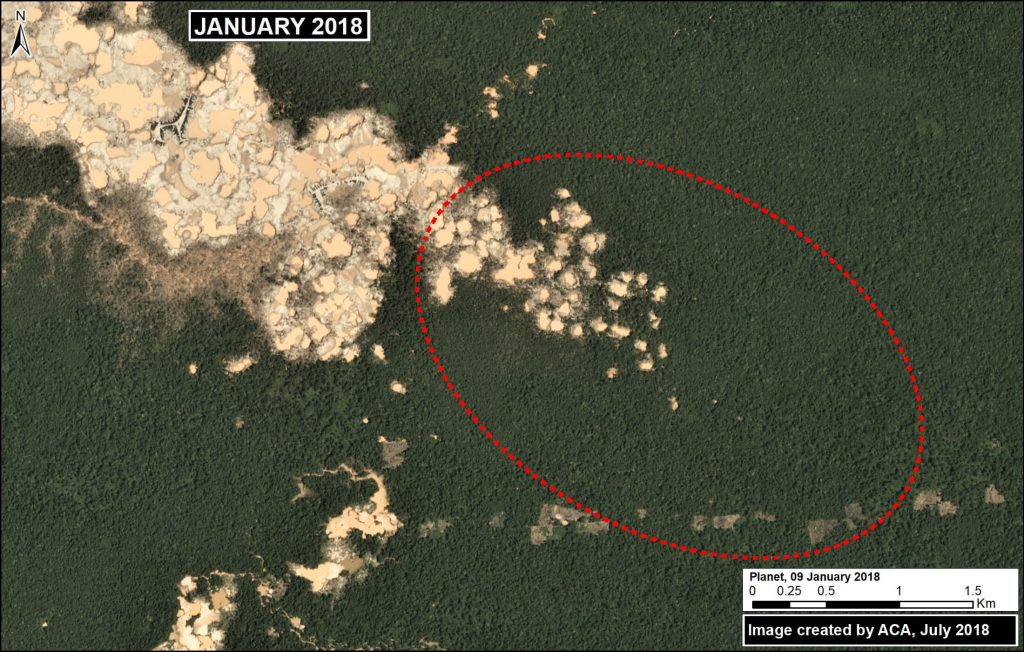

One of the main objectives is to improve the near real-time monitoring of deforestation and illegal logging.

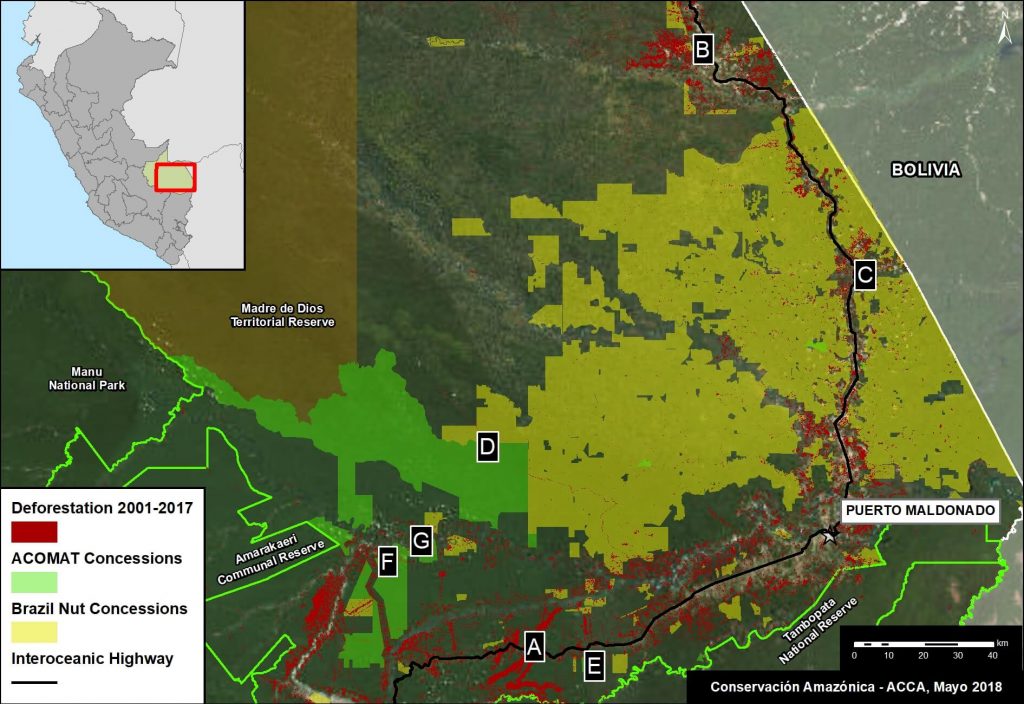

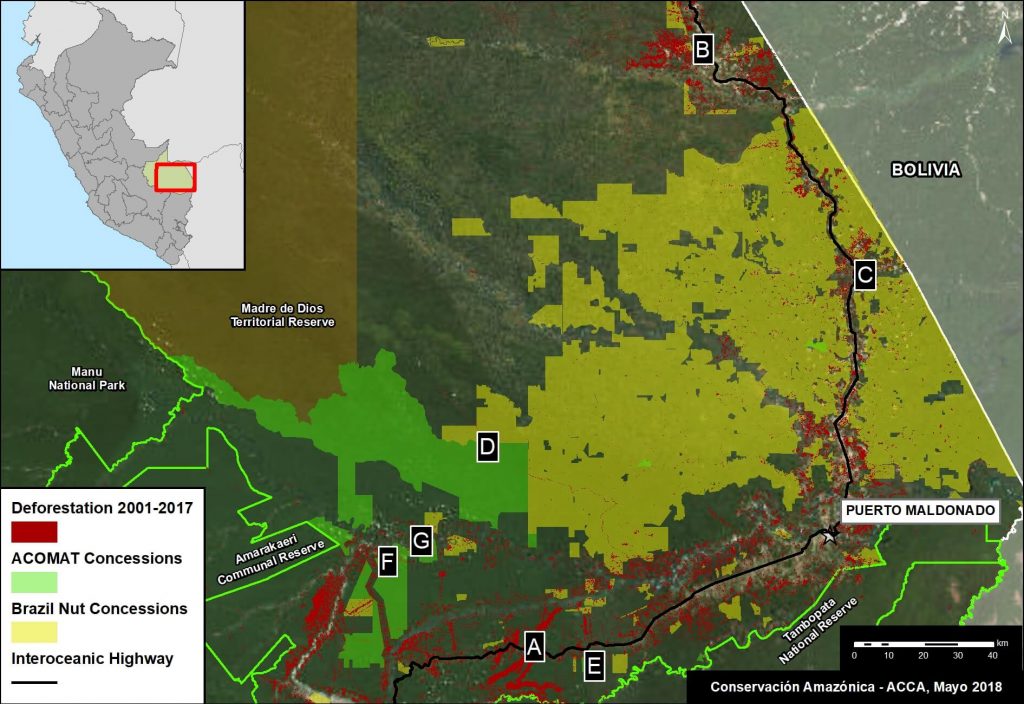

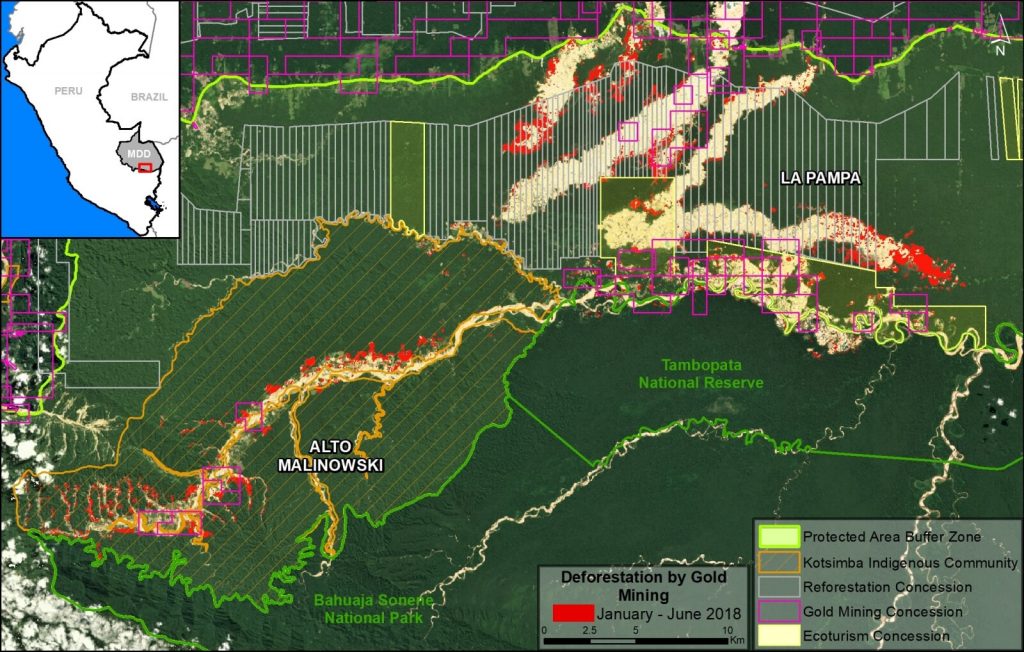

The monitoring is currently focused on three priority areas: 1) Brazil nut concessions, 2) forestry concessions of the local association ACOMAT, and 3) along the Interoceanic Highway (see Base Map).

Below, we show a series of drone images that we have used to identify the drivers of recent deforestation events. These drivers include gold mining, agriculture, illegal logging, cattle pasture, and natural forest loss.

Base Map. Priority areas of the Amazon Conservation drones initiative.

Interoceanic Highway

In March 2018, in collaboration with the organization ProPurús, we realized drone flights along the Interoceanic Highway in an effort to demonstrate the possible threats of building a new road along the border with Brazil (see MAAP #76). The following images show the two main threats to the area: gold mining and small/medium-scale agriculture (<50 hectares).

Image A. Drone image- gold mining.

B. Drone image- Deforestation from agriculture (corn)

Brazil Nut Concessions

In 2018, Amazon Conservation launched a new project, funded by Google Challenge, to develop a monitoring program for Brazil nut concessions covering a million hectares (2.47 million acres) in southern Peru. For example, the following image shows the invasion of a papaya plantation that caused the recent deforestation of five acres inside a concession.

C. Drone image- Invasion of papaya in Brazil nut concession.

ACOMAT Forestry Concessions

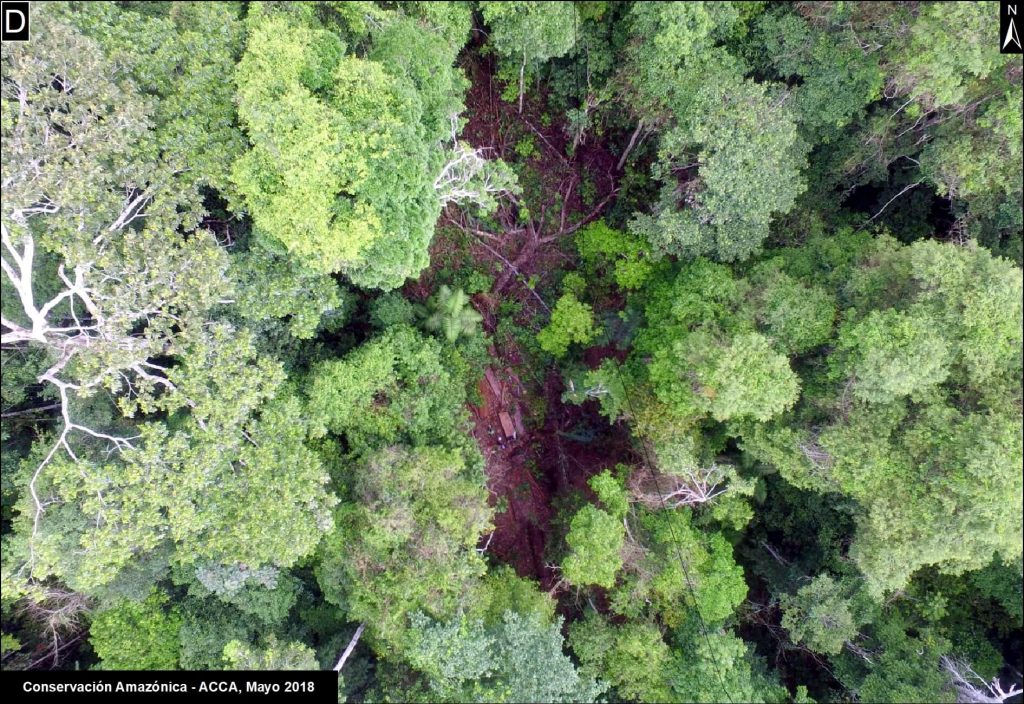

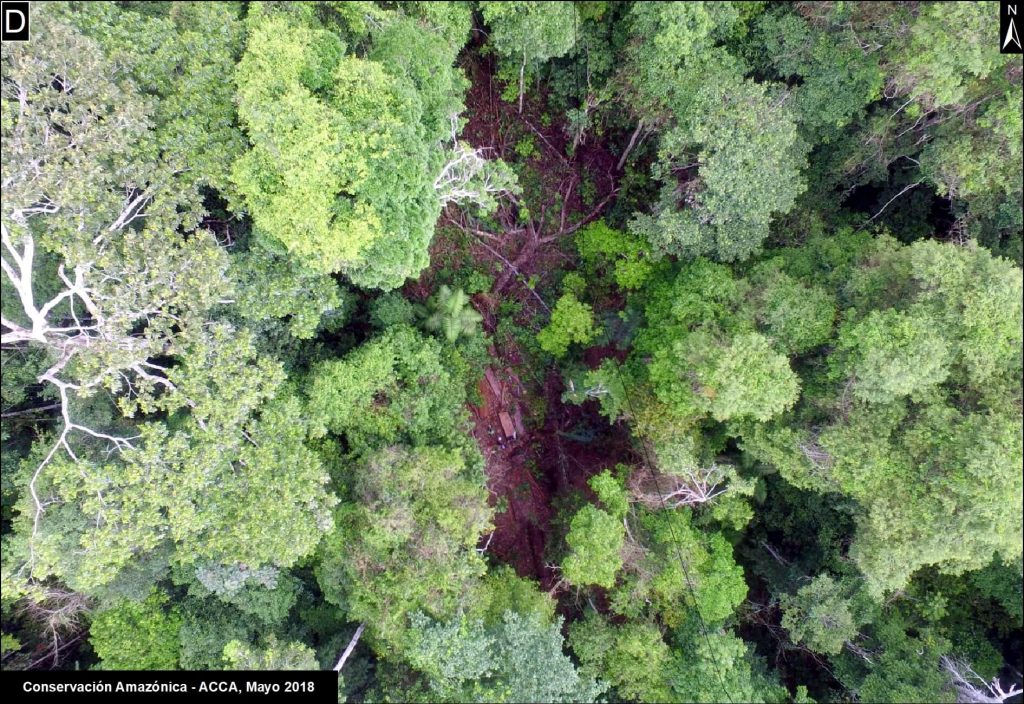

Since 2017, Amazon Conservation has been working on a project, financed by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), to improve the monitoring of forest concessions of the local association ACOMAT (Association of Timber and Non-Timber Forest Concessionaires of the Provinces from Manu and Tambopata). The following images show examples of forest loss and degradation due to illegal logging, cattle grazing, natural loss (windstorm), and gold mining.

D. Drone image- illegal logging.

E. Drone image- cattle pasture.

F. Drone image- natural forest loss from windstorm.

G. Drone image- gold mining.

Citation

Garcia R, Novoa S, Castañeda C, Rengifo P, Jimenez M, Finer M (2018) Using Drones to monitor Deforestation and Illegal Logging. MAAP: 90.

Loading...

Loading...