The rainforest is a highly diverse and complex ecosystem, of which only a very small percentage is known. Because the impact of different disturbances within it is not fully understood, protecting its integrity should be the end goal. However, the threats affecting this ecosystem are only increasing over time, including deforestation and mercury pollution caused by mining.

Mercury can be found in many forms, and while these are naturally available in the environment, a great amount results from its use in human activities like gold mining. Furthermore, although not all of its forms are toxic, methylmercury, the most bioavailable and toxic, bio-accumulates within the food chain, affecting a wide range of species. Bioaccumulation of this neurotoxin in birds has been seen to affect the fitness, coordination, reproduction and survival of species. Its effects include lethargy, loss of appetite, aberrant parenting behavior and reduced motivation to forage. Unfortunately, mercury’s persistence in the atmosphere and ability to travel great distances has allowed it to contaminate areas far from the original source.

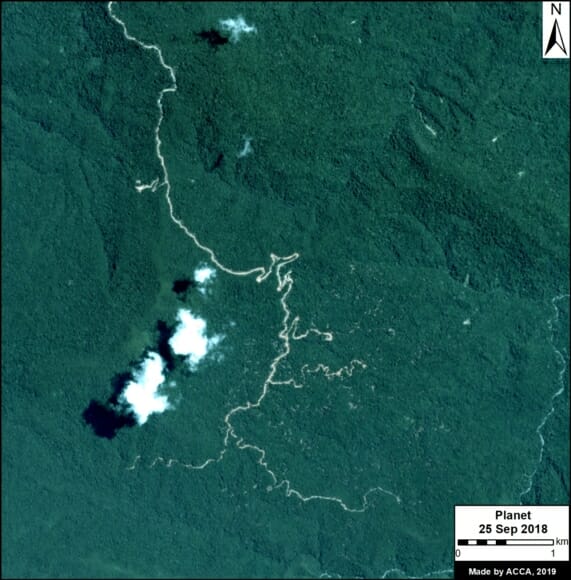

Roadside Hawk (Rupornis magnirostris) and a boat carrying oil for mining share the same ecosystem. PC: Patrick Newcombe

Aquatic systems are most efficient at converting mercury to methylmercury, increasing the risk of aquatic species. Because of this, much of the attention and studies of mercury contamination in birds has been focused on species associated with bodies of water. Conversely, terrestrial habitats and their wildlife have received little attention. Variations in soil moisture are expected to increase the bioavailability of mercury; increasing the risk of the long, wide, and complex food webs found in tropical systems.

Because birds are often near or in the top of food chains, they are highly prone to accumulating mercury in their bodies. However, this fact does also make them very good bio-indicators of environmental mercury contamination. They are common, conspicuous, and sampling of feathers and eggshells can confidently detect levels of heavy metals in a non-invasive manner. Particularly in tropical rainforests, more work needs to be done to assess the impact of mercury on birds.

The increasing threat mercury pollution poses to the tropics is drawing more and more attention to this region. As a short-term measure, it is necessary to replace current gold mining techniques, with already existing mercury-free methods. By moving away from this metal, we will ensure healthy human and wildlife communities and more crucially a healthy ecosystem.

Further readings:

Egwumah F.A, Egwumah P.O & Edet, D.I. (2017). Paramount roles of wild birds as bioindicators of contamination. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2(1):194‒200. DOI: 10.15406/ijawb.2017.02.00041

Appel, Peter & Jøsson, J.B.. (2010). Borax – an alternative to mercury for gold extraction by small-scale miners: Introducing the method in Tanzania. Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland Bulletin. 87-90.

Jessica Pisconte holds a degree in biology from the Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga de Ica, Peru. Her interest in avian conservation was born in the Paracas National Reserve, after which she joined a wide range of research projects to learn about the importance of birds in coastal, mountain and Amazonian ecosystems. She is currently working as a park ranger in the Tambopata National Reserve in Peru’s Madre de Dios region. As the threats due to illegal mining increased in this region, seriously affecting the environment, Jessica was motivated to research key areas to understand its impact. Los Amigos will be her starting point to study the effects on birds of mercury from gold mining. Through this project, Jessica seeks to contribute to the conservation of and knowledge regarding birds in the Peruvian Amazon.

Jessica Pisconte holds a degree in biology from the Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga de Ica, Peru. Her interest in avian conservation was born in the Paracas National Reserve, after which she joined a wide range of research projects to learn about the importance of birds in coastal, mountain and Amazonian ecosystems. She is currently working as a park ranger in the Tambopata National Reserve in Peru’s Madre de Dios region. As the threats due to illegal mining increased in this region, seriously affecting the environment, Jessica was motivated to research key areas to understand its impact. Los Amigos will be her starting point to study the effects on birds of mercury from gold mining. Through this project, Jessica seeks to contribute to the conservation of and knowledge regarding birds in the Peruvian Amazon. Lisset Goméz studied biological sciences at the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos in Lima, Peru. Her interests include ecology, reproductive biology, and conservation of bird communities, and she has been involved in a number of courses and projects around Peru that embrace these topics. Lisset volunteered with the National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP) and at the Wayquecha Biological Station, where she assisted in a project on plant-hummingbird interactions. Through her participation in the Course on Field Techniques and Tropical Ecology at the Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manu National Park, she strengthened her knowledge of the tropical forest and started conducting her own research. As a Franzen Fellow, she will try to understand the habitat requirements of woodpeckers of the genera Campephilus and Celeus. She will address her research question by identifying the woodpecker species’ tree preferences when excavating their nesting cavities.

Lisset Goméz studied biological sciences at the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos in Lima, Peru. Her interests include ecology, reproductive biology, and conservation of bird communities, and she has been involved in a number of courses and projects around Peru that embrace these topics. Lisset volunteered with the National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP) and at the Wayquecha Biological Station, where she assisted in a project on plant-hummingbird interactions. Through her participation in the Course on Field Techniques and Tropical Ecology at the Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manu National Park, she strengthened her knowledge of the tropical forest and started conducting her own research. As a Franzen Fellow, she will try to understand the habitat requirements of woodpeckers of the genera Campephilus and Celeus. She will address her research question by identifying the woodpecker species’ tree preferences when excavating their nesting cavities. Diego Guevara got his biology degree from the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM) in Lima, Peru and holds a master’s degree in applied ecology from the University of East Anglia, UK. He is an associate researcher at the Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) and general coordinator of the UNALM banding station. He has experience in projects related to the impact of human activities on biodiversity, with a special interest in the responses of bird communities and the habitat requirements of endangered species. Additionally, he is interested in studying the ecotoxicology and physiology of birds, which led him to apply to the Franzen Fellowship. His project will focus on the fluvial and bamboo forest bird community, studying the impacts of mining on its bird communities.

Diego Guevara got his biology degree from the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM) in Lima, Peru and holds a master’s degree in applied ecology from the University of East Anglia, UK. He is an associate researcher at the Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) and general coordinator of the UNALM banding station. He has experience in projects related to the impact of human activities on biodiversity, with a special interest in the responses of bird communities and the habitat requirements of endangered species. Additionally, he is interested in studying the ecotoxicology and physiology of birds, which led him to apply to the Franzen Fellowship. His project will focus on the fluvial and bamboo forest bird community, studying the impacts of mining on its bird communities. Patrick Newcombe attends the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., making him the youngest of our fellows. His interest in birds started as a young child, leading to his engagement in bird research. In 2018, with Osa Conservation in Costa Rica, he collected field data on the flocking behavior and diet of the endangered black-cheeked ant tanager (Habia atrimaxillaris). He is currently analyzing weather surveillance radar data to study the flight strategies of migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway as part of a project led by Dr. Kyle Horton from Cornell University. At Los Amigos, his project will focus on Manakin leks around the station, from which he will identify and learn about their habitat use patterns.

Patrick Newcombe attends the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., making him the youngest of our fellows. His interest in birds started as a young child, leading to his engagement in bird research. In 2018, with Osa Conservation in Costa Rica, he collected field data on the flocking behavior and diet of the endangered black-cheeked ant tanager (Habia atrimaxillaris). He is currently analyzing weather surveillance radar data to study the flight strategies of migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway as part of a project led by Dr. Kyle Horton from Cornell University. At Los Amigos, his project will focus on Manakin leks around the station, from which he will identify and learn about their habitat use patterns.

Loading...

Loading...