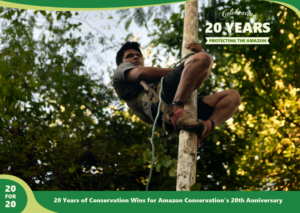

Due to a misstep coming down the tree with a heavy branch of açaí in hand, Omar Espinoza, an açaí harvester, fell from a height of about 40 feet head first. He was gathering fruits to support his family and like many açaí harvesters, was climbing 10-15 açaí trees a day with heights reaching up to 65 feet to bring down bundles of açaí weighing dozens of pounds.

Due to a misstep coming down the tree with a heavy branch of açaí in hand, Omar Espinoza, an açaí harvester, fell from a height of about 40 feet head first. He was gathering fruits to support his family and like many açaí harvesters, was climbing 10-15 açaí trees a day with heights reaching up to 65 feet to bring down bundles of açaí weighing dozens of pounds.

Thanks to one of the features in our newly developed safety harnesses distributed earlier in the year, Omar’s misstep was not fatal and due to the harness’s aptly named “life line”, he was stopped from hitting the ground. Instead Omar just dangled from the harness, his head a few feet above the forest floor. Using the harness he had before this project would have meant a certain fall. Had it not been for this new equipment, he would have faced severe and debilitating injuries or possibly, death.

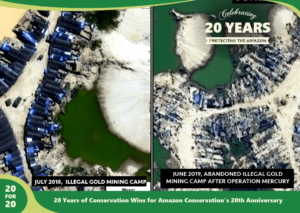

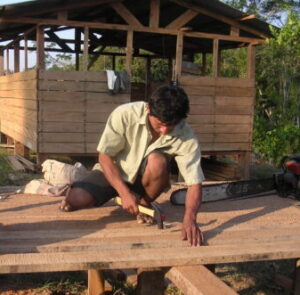

These harnesses are a practical conservation tool because they promote (and improve the safety of) forest-friendly livelihoods such as the sustainable gathering of brazil nuts and acai berries. These activities are safer, more profitable, and encourage conservation of standing forests compared to activities such as gold mining, logging, or agriculture, which results in forest habitats being cleared.

For many years now, we have been working with açaí and Brazil nut harvesters who depend on the Santa Rosa de Abuná conservation area and have helped improve how harvesters locate, gather, and process the forest goods they sustainably harvest. This is a key conservation and community development strategy for providing local people with the incentive to keep forests standing, as many of the globally in-demand fruits and nuts they harvest can only grow in healthy forests – not in large-scale plantations. With this strategy in mind, we help families improve their income by growing their local economies through instituting ecologically sustainable activities that protect the forests they call home.

This story is part of a series commemorating our 20th anniversary protecting the Amazon. We’re celebrating this milestone with a look back at our 20 biggest conservation wins over the past 20 years. Click here to help create more life saving tools that help local harvesters in the Amazon.

Details:

Details:

Loading...

Loading...