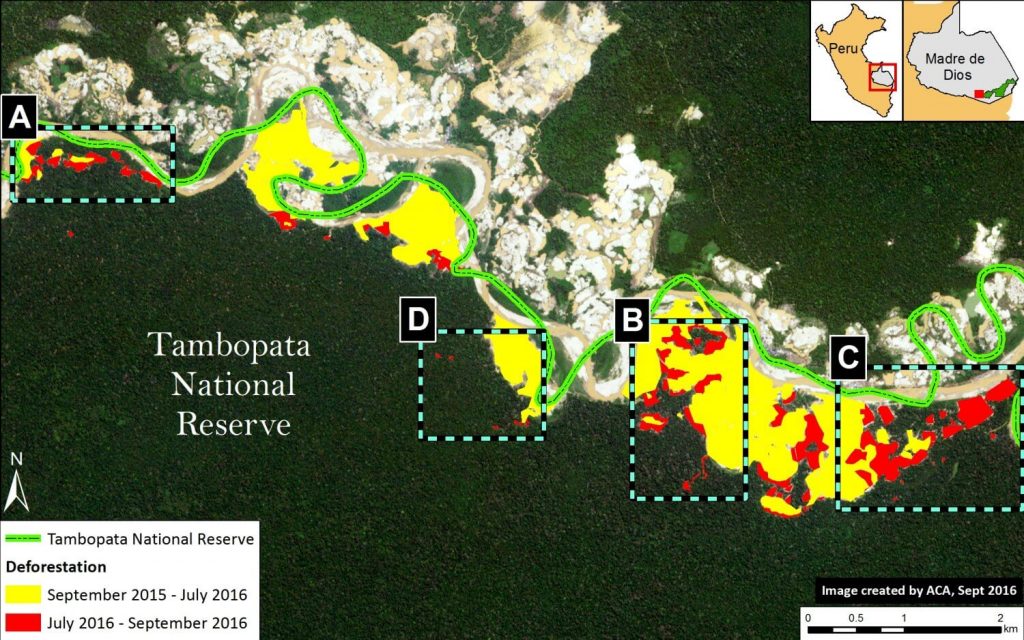

In previous articles, we documented the illegal gold mining invasion of Tambopata National Reserve (Madre de Dios region in the southern Peruvian Amazon) in November 2015 and the subsequent deforestation of 350 hectares as of July 2016. Here, we report that the mining deforestation in the Reserve now exceeds 450 hectares (1,110 acres) as of September 2016. Image 46a illustrates the extent of the invasion, with red indicating the most recent deforestation fronts. Insets A-D indicate the location of the high-resolution zooms below.

Uncategorized

MAAP #45: Threats To El Sira Communal Reserve in Central Peruvian Amazon

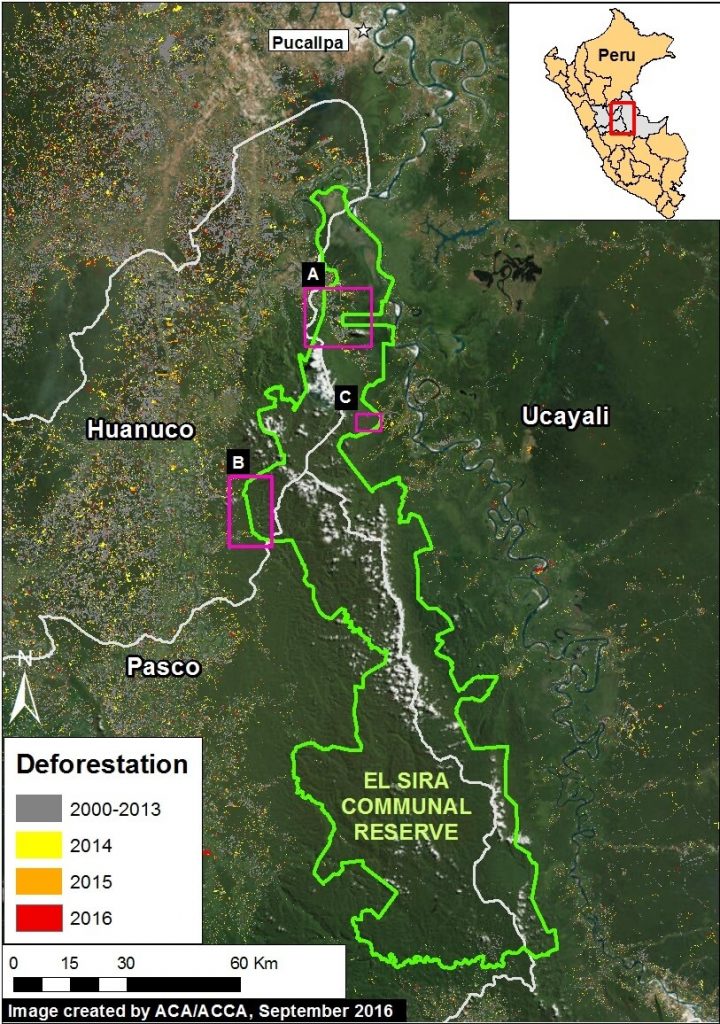

El Sira Communal Reserve, located in the central Peruvian Amazon (regions of Pasco, Huánuco and Ucayali), aims to protect the biological diversity of the El Sira Mountain Range in benefit of the native communities of the area (Ashaninka, Yanesha, and Shipibo-Conibo indigenous groups).

This report presents an initial threat assessment for this large national protected area, which covers more than 615,000 hectares (1.5 million acres).

We identified 3 threatened sectors of the Reserve, as indicated in Image 45a (see Insets A-C).

We found that the principal drivers of deforestation in these three sectors are agriculture & cattle pasture (Insets A and C) and illegal gold mining (Inset B).

It is important to note that the deforestation for agriculture & cattle pasture continues to rapidly increase – 1,600 hectares (3,950 acres) since 2013 – while the deforestation for gold mining has been limited due to regular interventions by the Peruvian government.

Below, we show high-resolution satellite images of the recent deforestation in all three threatened sectors. Click each image to enlarge.

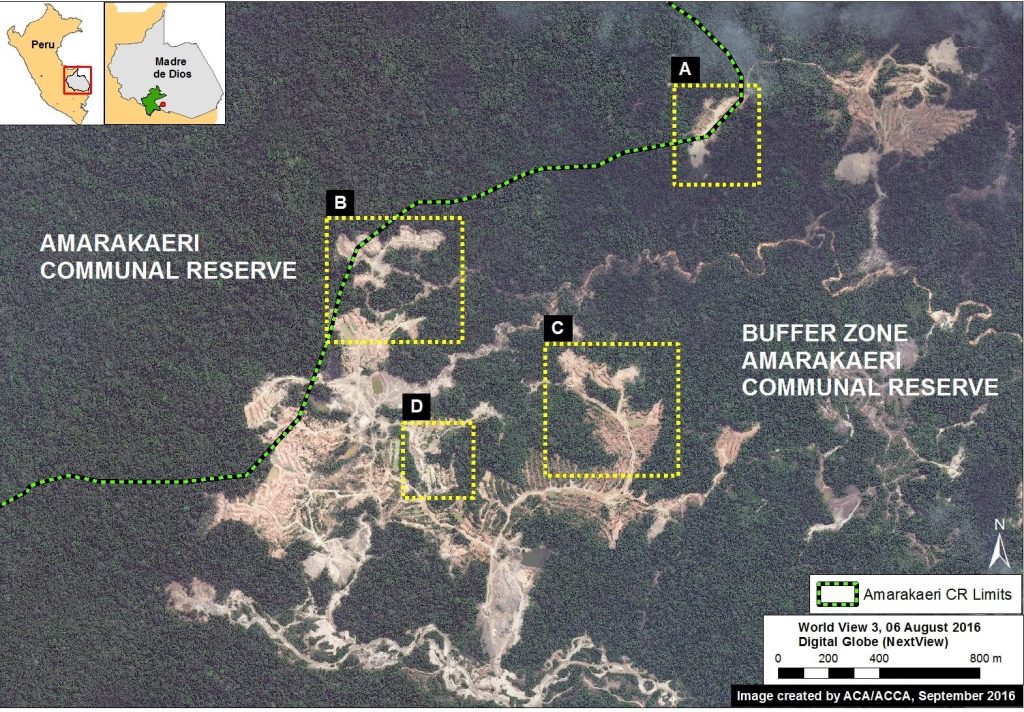

MAAP# 44: Potential Recuperation of Illegal Gold Mining Area in Amarakaeri Communal Reserve

In the previous MAAP #6, published in June 2015, we documented the deforestation of 11 hectares in the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve due to a recent illegal gold mining invasion. The Reserve, located in the Madre de Dios region of the southern Peruvian Amazon, is an important protected area that is co-managed by indigenous communities and Peru’s National Protected Areas Service (known as SERNANP). In the following weeks, the Peruvian government, led by SERNANP, cracked down on the illegal mining activities and effectively halted the deforestation within that part of the Reserve.

Here, we present high-resolution satellite images that show an initial vegetation regrowth in the invaded area. This finding may represent good news regarding the Amazon’s resilience to recover from destructive mining if it is stopped at an early stage. However, many questions and caveats remain regarding the nature of the regrowth and the long-term recovery potential of the degraded land, please see the Additional Information section below for more details.

Image 44a shows the base map of the area invaded by illegal gold mining in the southeast sector of Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. Insets A–D indicate the areas featured in the high-resolution zooms below.

MAAP #43: Early Warning Deforestation Alerts in The Peruvian Amazon, Part 2

In the previous MAAP #40, we emphasized the power of combining early warning forest loss GLAD alerts with analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery as part of a comprehensive near real-time deforestation monitoring system for the Peruvian Amazon.

In the current MAAP, we present 3 new examples of this system across different regions of Peru. Click on the images below to enlarge.

Example 1: Illegal Gold Mining in buffer zone of Bahuaja Sonene National Park (Madre de Dios)

Example 2: Logging Road in buffer zone of Cordillera Azul National Park (Ucayali/Loreto)

Example 3: Deforestation in Permanent Production Forest (Ucayali)

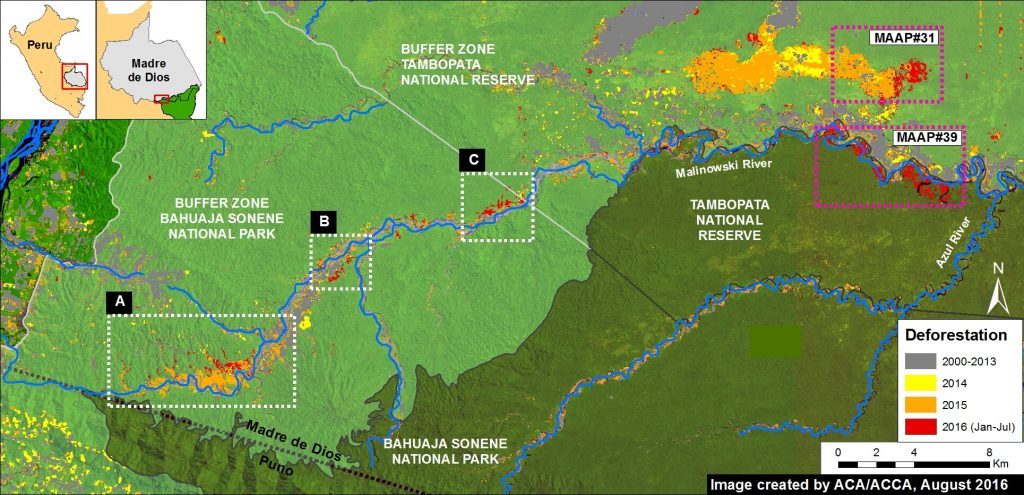

Example 1: Illegal Gold Mining in buffer zone of Bahuaja Sonene National Park (Madre de Dios)

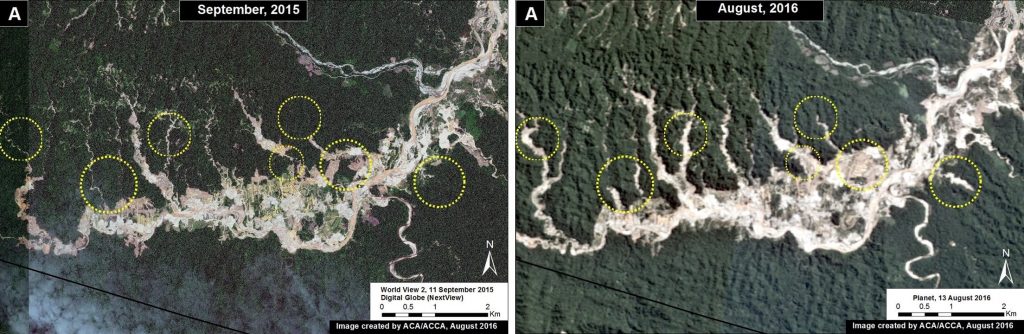

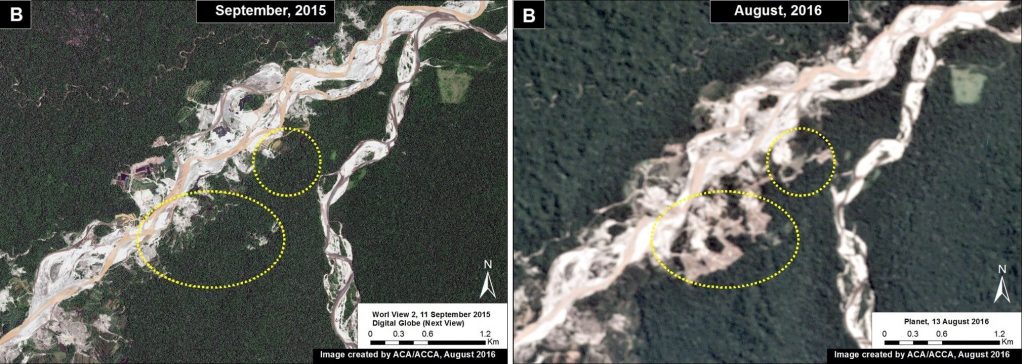

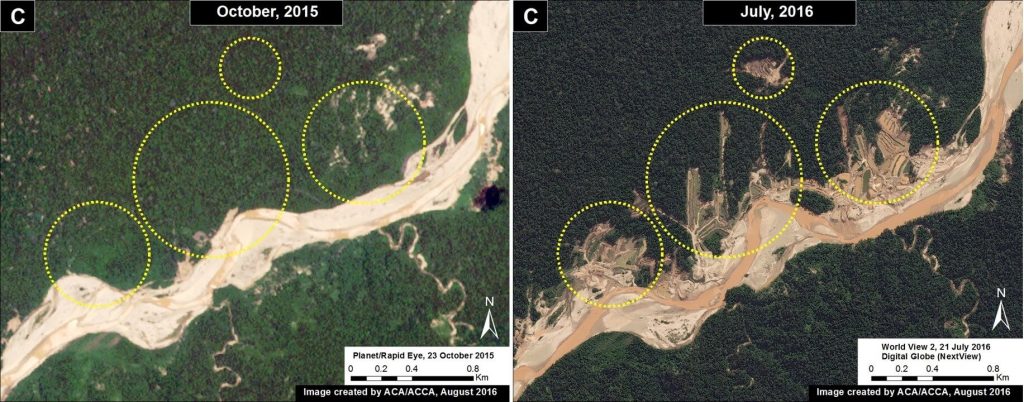

In the previous MAAP #5, we discussed illegal gold mining deforestation along the upper Malinowski River, located in the buffer zone of the Bahuaja Sonene National Park. As seen in Image 43a, the upper Malinowski is just upstream of the areas invaded by illegal gold mining in Tambopata National Reserve and its buffer zone (see MAAP #39 and #31, respectively). In MAAP #5, we documented the deforestation of more than 850 hectares between 2013 and 2015 along the upper Malinowski. Here, we show that gold mining deforestation continues in 2016, with an additional loss of 238 hectares (806 acres). Insets A-C correspond to the areas featured in the high-resolution zooms below.

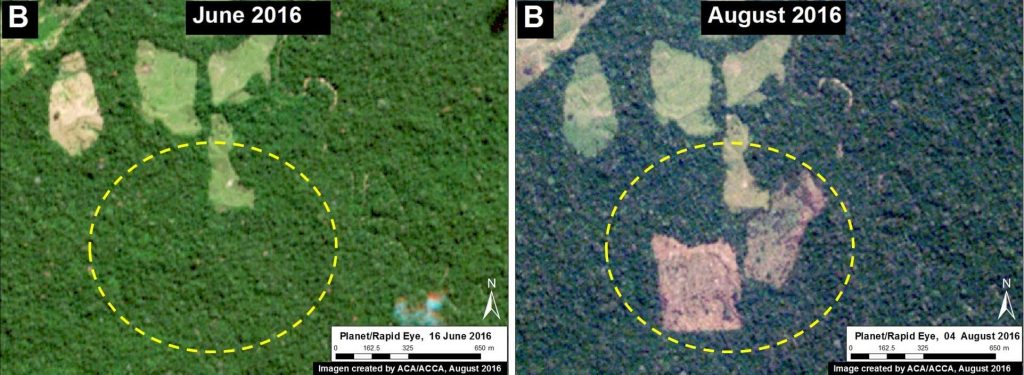

The following Images 43b-d show, in high-resolution, the rapid expansion of gold mining deforestation between August/September 2015 (left panel) and July/August 2016 (right panel). The yellow circles indicate the main areas of deforestation between the images.

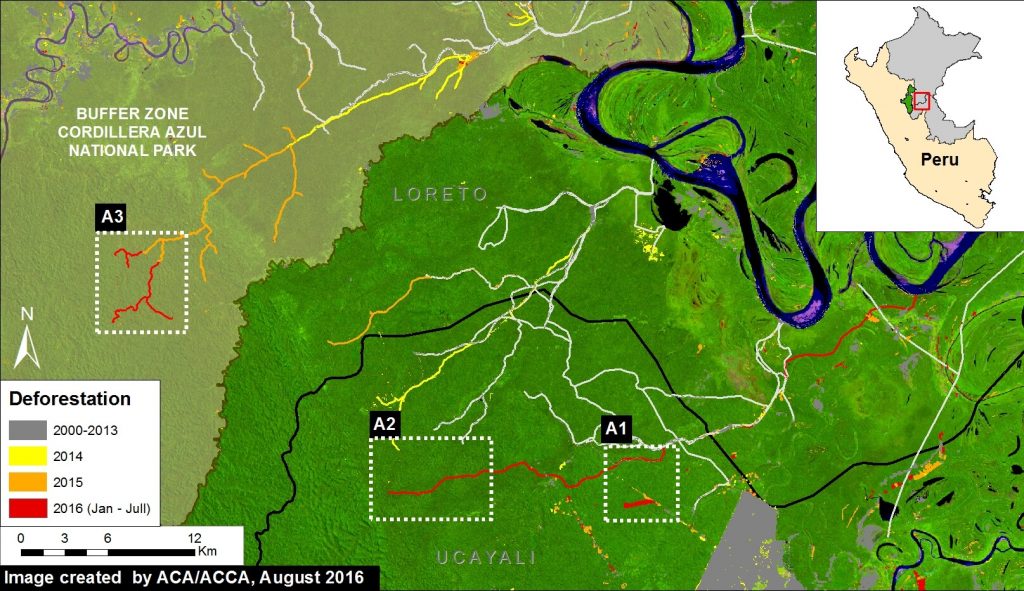

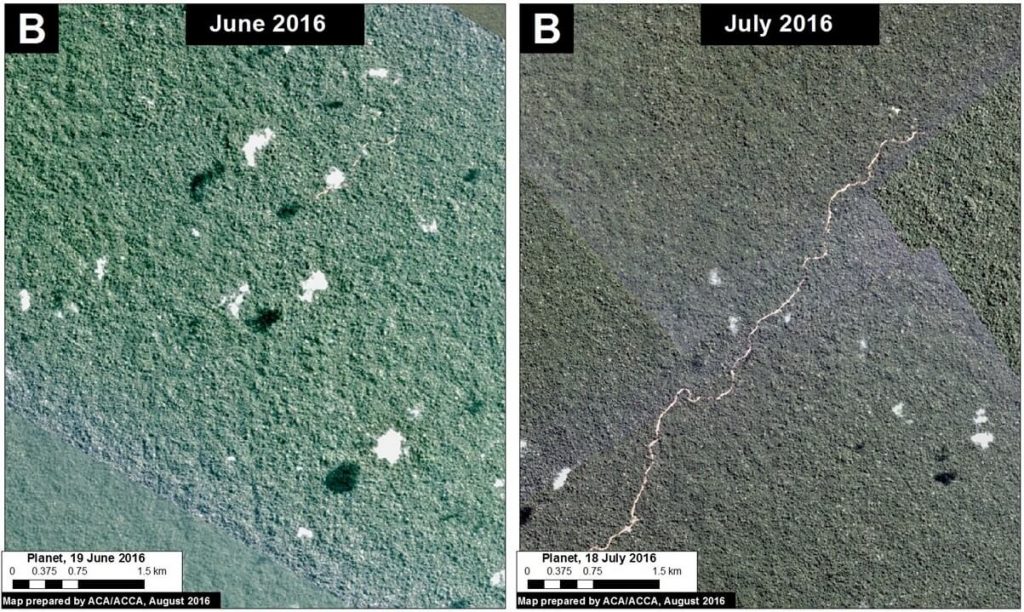

Example 2: Logging Road in buffer zone of Cordillera Azul National Park (Ucayali/Loreto)

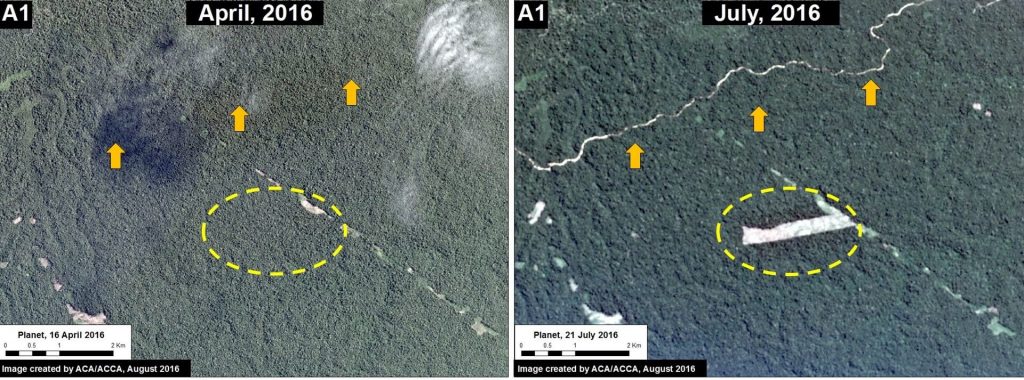

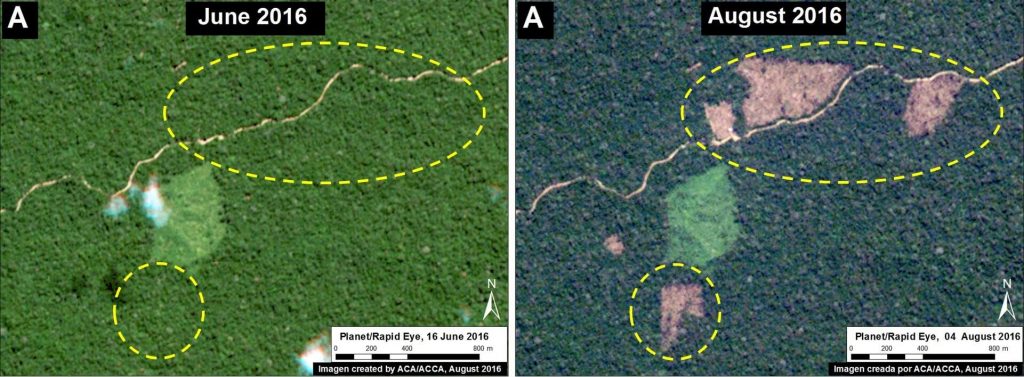

In the previous MAAP #18, we discussed the proliferation of logging roads in the central Peruvian Amazon in 2015. Here, we show the expansion of two of these logging roads in 2016. (see Image 43e). Red indicates construction during 2016 (47 km). Insets A1-A3 correspond to the areas featured in the high-resolution zooms below. Note that the northern road (Inset A3) is within the buffer zone of Cordillera Azul National Park. Evidence suggests that this road is not legal because it extends out of the permited area (see MAAP #18 for more details).

The following images show, in high-resolution, the rapid construction of these logging roads. Image 43f shows the construction of part of the southern road (Inset A1), and the deforestation for a nearby agricultural parcel, between April (left panel) and July (right panel) 2016. Image 43g shows the construction of 1.8 km in just three days along this same road (Inset A2) between July 21 (left panel) and July 24 (right panel) 2016.

Image 43h shows the construction of 13 km on the northern road between November 2015 (left panel) and July 2016 (right panel) within the buffer zone of the Cordillera Azul National Park.

Example 3: Deforestation in Permanent Production Forest (Ucayali)

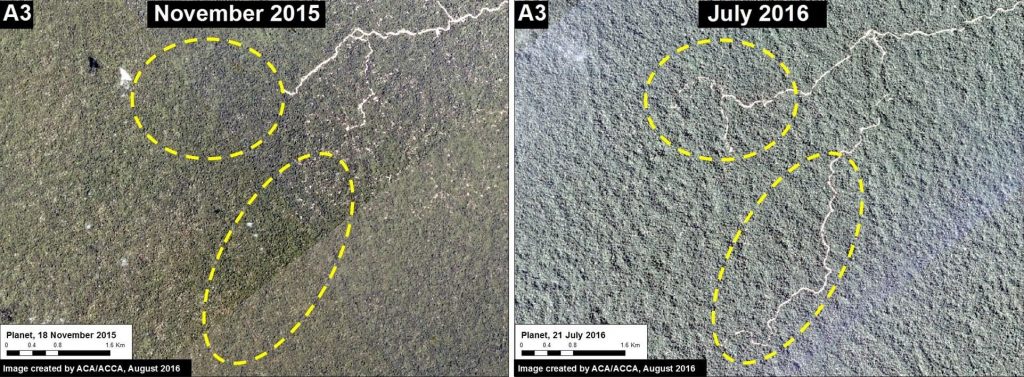

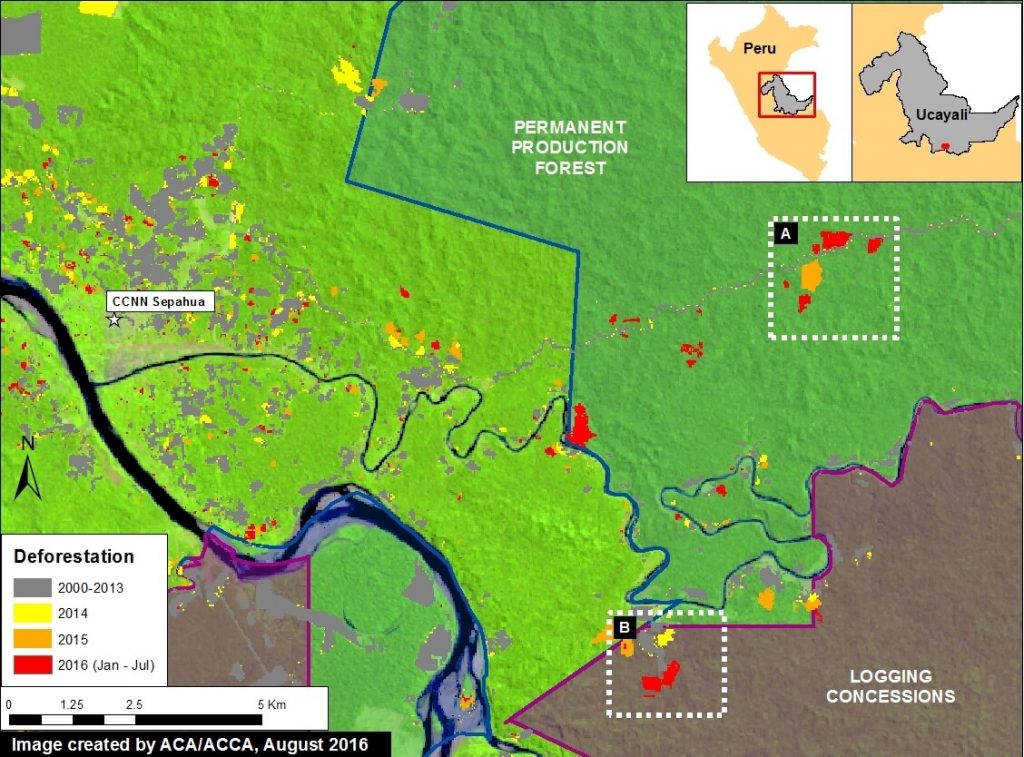

Image 43i shows recent deforestation of 136 hectares (336 acres) in 2016 in southern Ucayali region within areas classified as Permanent Production Forest and Foresty Concession. These types of areas are generally zoned for sustainable forestry uses, not clear-cutting, thus we question the legality of the deforestation. Tables A-B correspond to the areas featured in the high-resolution zooms, below.

Image 43j shows deforestation within a section of Permanent Production Forest, and Image 43k shows deforestation within a section of Forestry Concession.

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S, Goldthwait E (2016) Early Warning Deforestation Alerts in the Peruvian Amazon, Part 2. MAAP: 43.

MAAP #42: Papaya – New Deforestation Driver in Peruvian Amazon

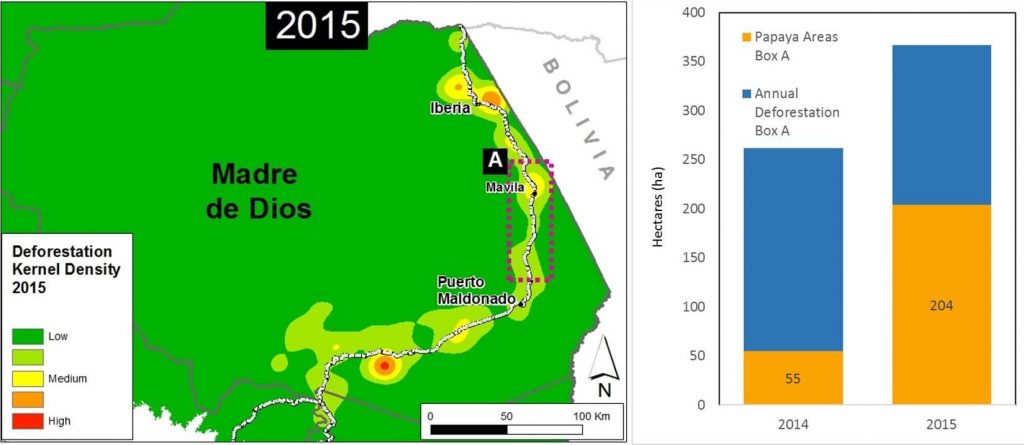

In the previous MAAP #26, we published a preliminary map of Deforestation Hotspots in the Peruvian Amazon for 2015. Subsequently in 2016, we have been compiling information to improve understanding on the potential causes (drivers) of deforestation in the identified hotspots. In this article, we focus on a medium-intensity hotspot located along the newly paved Interoceanic Highway in the eastern part of the Madre de Dios region (see Inset A in Image 42a).

The analysis in this article is based on field work carried out by the Peruvian Ministry of Environment, in collaboration with Terra-i. This team has verified the presence of papaya plantations in the area indicated by Inset A and shared their photos and coordinates with MAAP to allow us to search for and analyze relevant satellite imagery.

Synthesizing all of the available information, we found that the establishment of papaya plantations was an important deforestation driver in the area in 2015. Within the focal area (Inset A), we estimate the deforestation of 204 hectares (504 acres) for papaya plantations in 2015, a major increase relative to 2014 (see bar graph in Image 42a).

All of the papaya deforestation is small (< 5 hectares) or medium (5-50 hectares) scale. According to the analysis presented in MAAP #32, these two scales represented 99% of the deforestation events in Peru in 2015. Approximately 90% of the observed deforestation is within areas zoned for agricultural activity. Therefore, the legality of the deforestation in not known (i.e. if all the required permits were obtained).

Below, we show satellite images and field photos of 5 examples of the recent deforestation caused by papaya cultivation.

Example #1

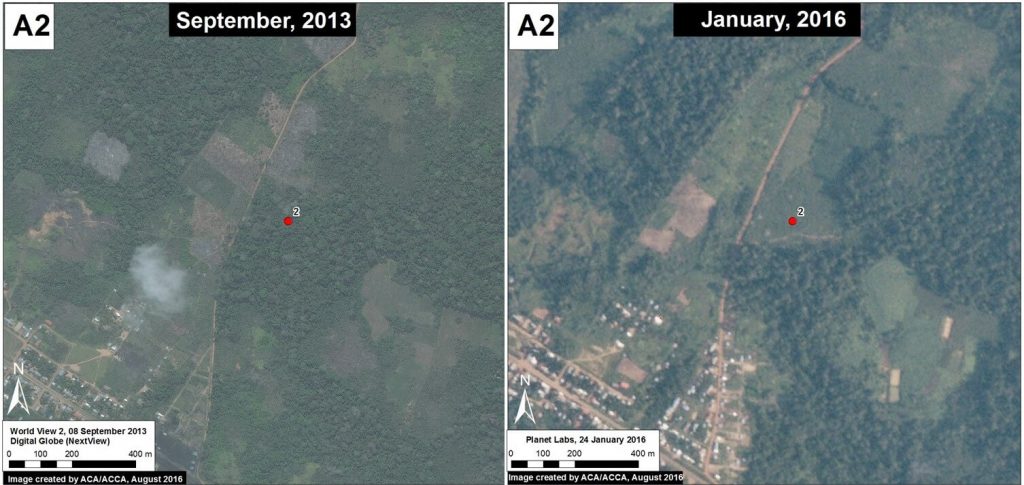

Image 42b shows the deforestation of 12 hectares between September 2013 (left panel) and January 2016 (right panel). The red point indicates the same place in both images. Image 42c is a photo of the new papaya plantation in this area.

Example #2

Image 42d shows the deforestation of 5 hectares between September 2013 (left panel) and January 2016 (right panel). The red point indicates the same place in both images. Image 42e is a photo of the new papaya plantation in this area.

Example #3

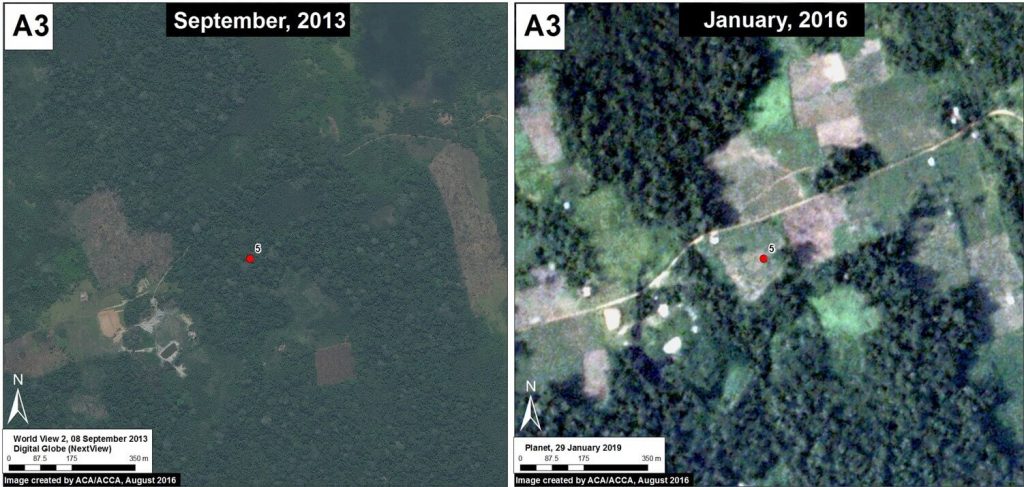

Image 42f shows the deforestation of 5 hectares between September 2013 (left panel) and January 2016 (right panel). The red point indicates the same place in both images. Image 42g is a photo of the new papaya plantation in this area.

Example #4

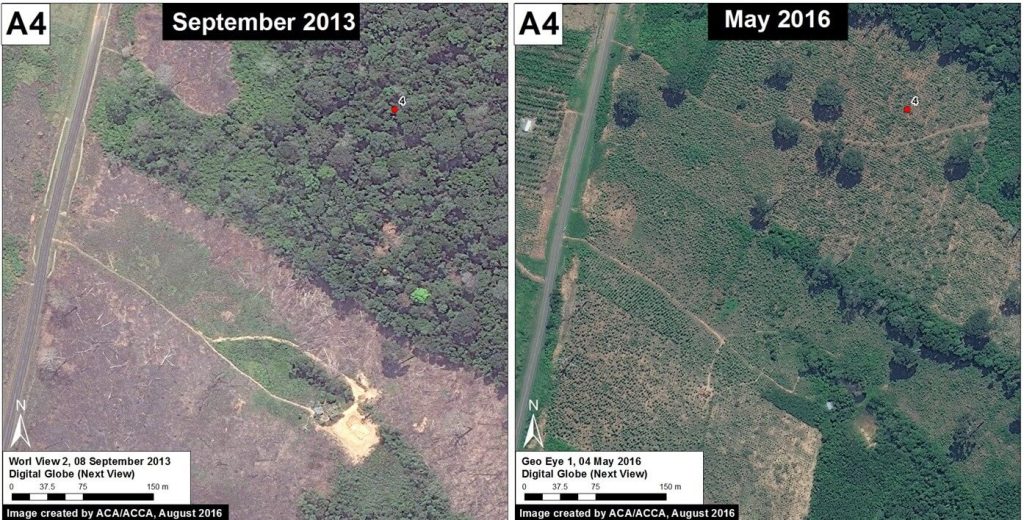

Image 42h shows the deforestation of 12 hectares between September 2013 (left panel) and May 2016 (right panel). The red point indicates the same place in both images. Image 42i is a photo of the new papaya plantation in this area.

Example #5

Image 42j shows the deforestation of 9 hectares between April 2015 (left panel) and May 2016 (right panel). The yellow boxes indicate the same place in both images. Image 42k is a photo of the new papaya plantation in this area.

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S, Carrasco F (2016) Papaya – Potential New Driver of Deforestation in Madre de Dios. MAAP: 42.

MAAP #41: Confirming Large-Scale Oil Palm Deforestation in The Peruvian Amazon

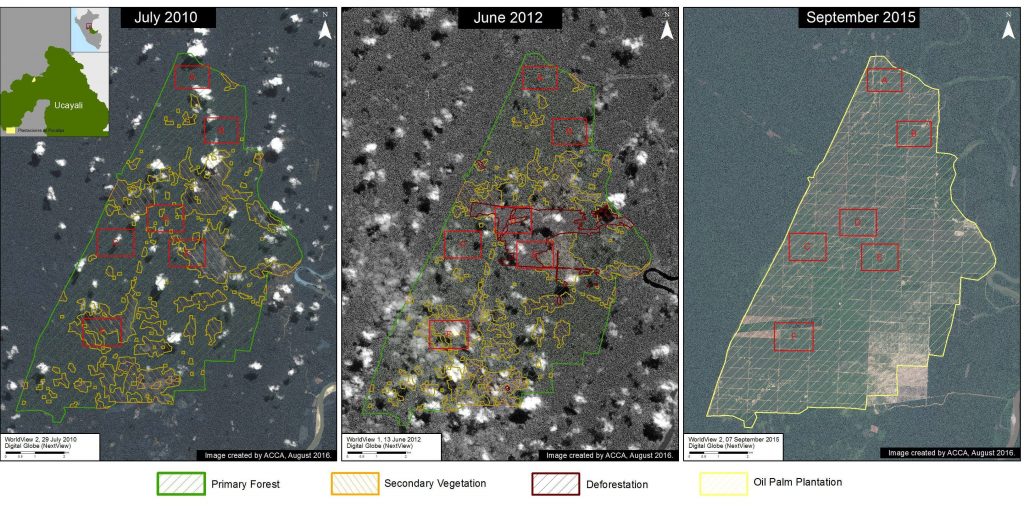

In the previous MAAP #4, we documented the deforestation of 6,464 hectares (15,970 acres) between 2011 and 2015 associated with a large-scale oil palm project in the central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali region) operated by the company Plantaciones de Pucallpa. In addition, we found that the majority of this deforestation occurred in primary forests,1 although there was also clearing of secondary vegetation.

In December 2015, the Native Community of Santa Clara de Uchunya presented an official complaint to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) against Plantaciones de Pucallpa, a member of the roundtable. An important component of the complaint centers on the deforestation described above, however the company has repeatedly denied causing it.

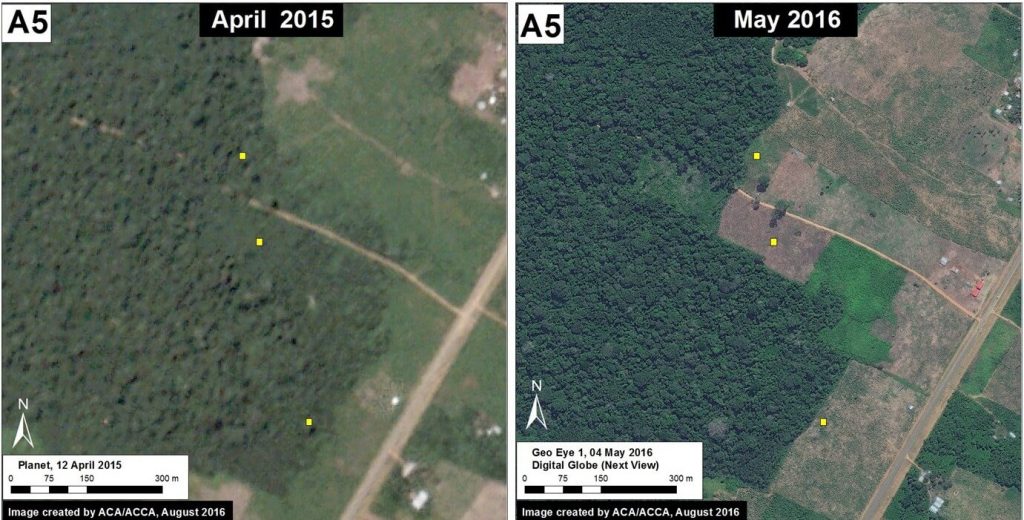

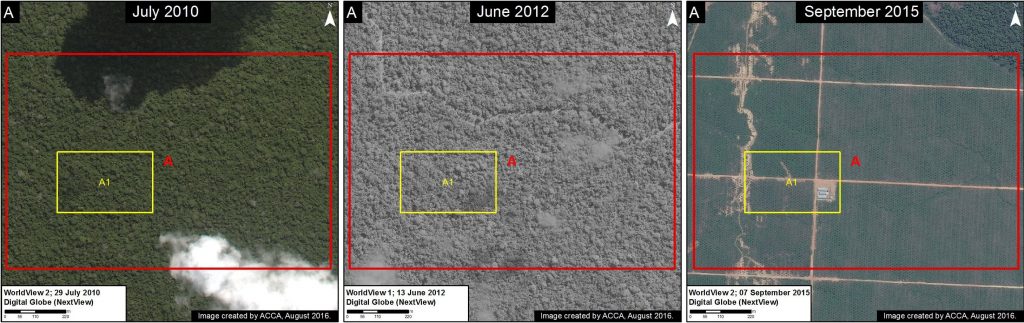

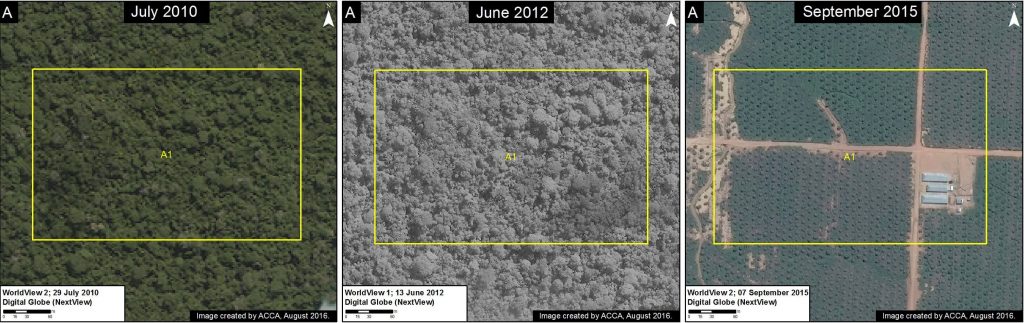

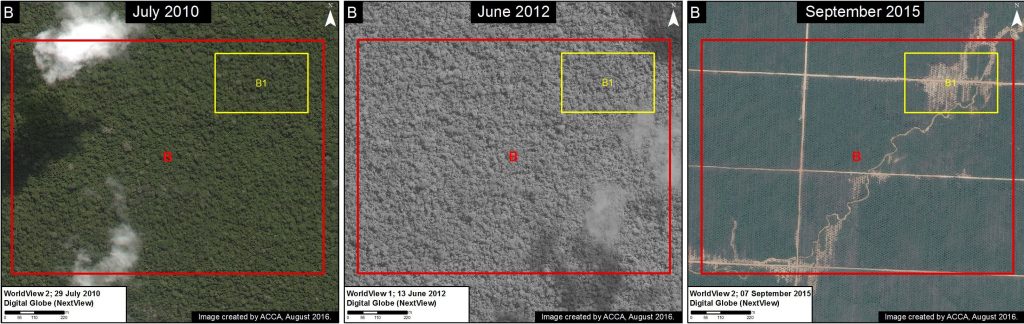

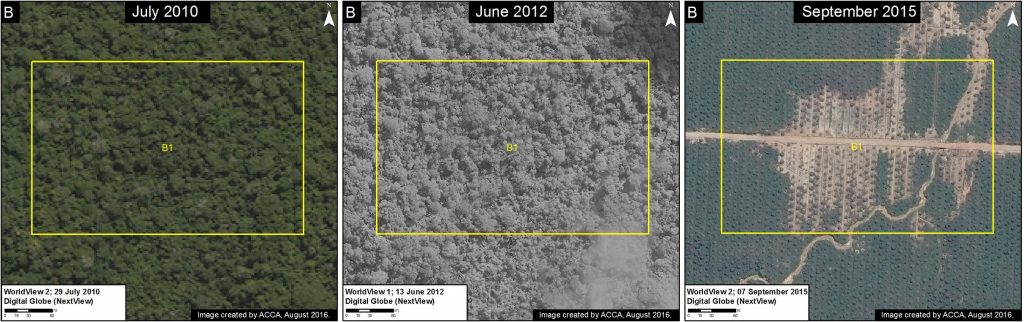

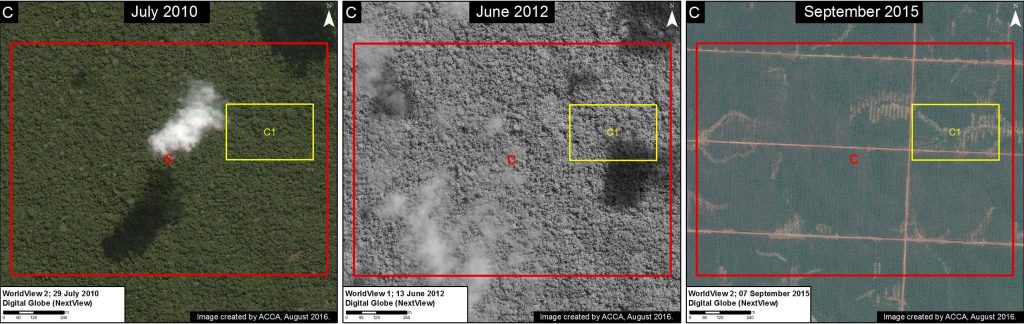

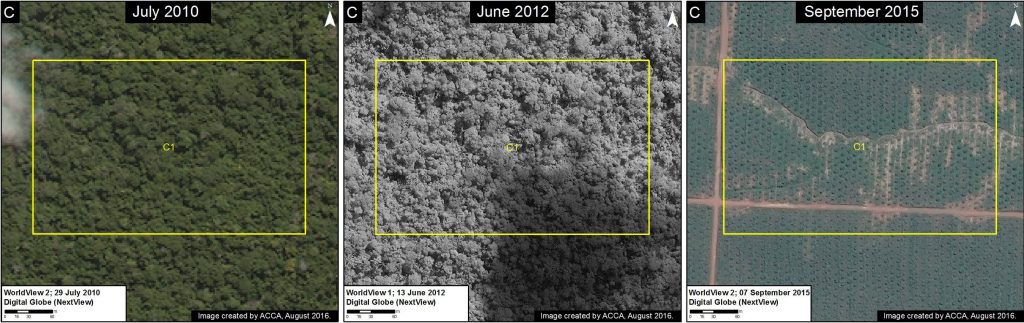

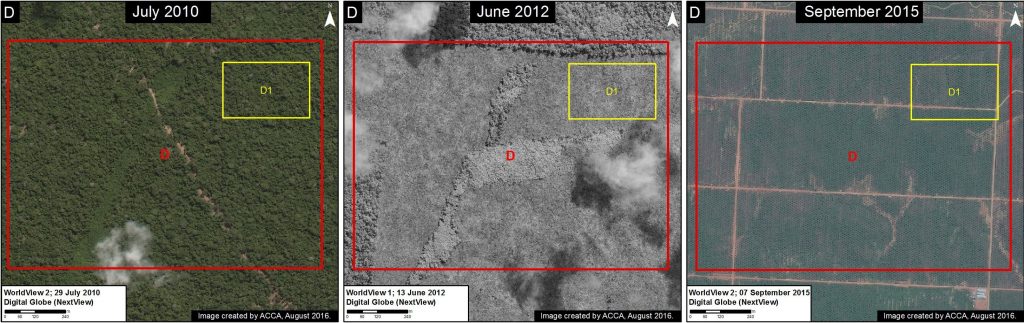

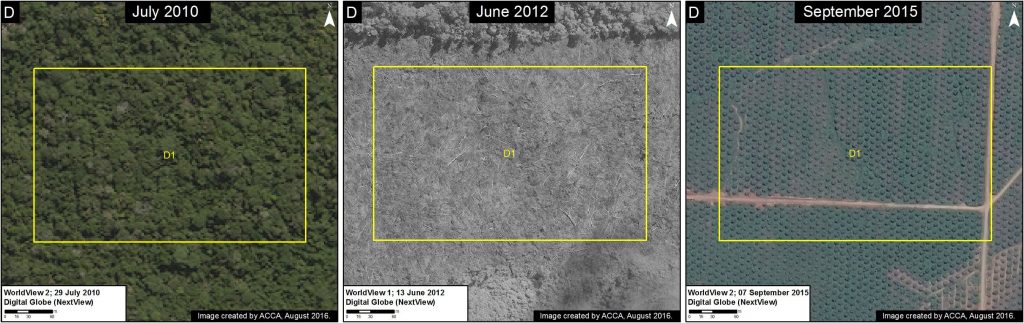

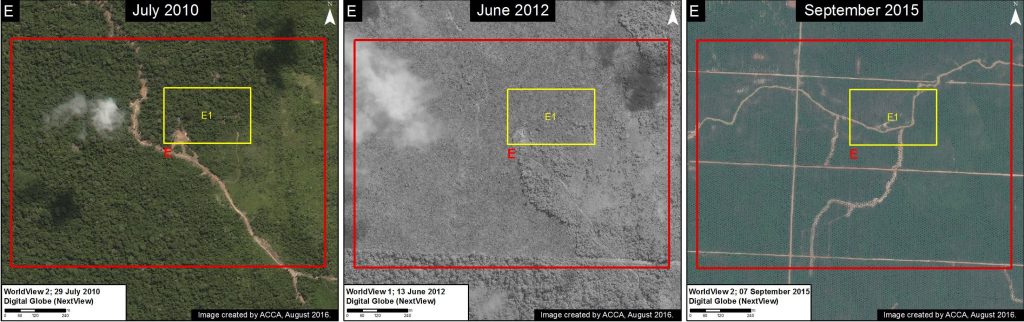

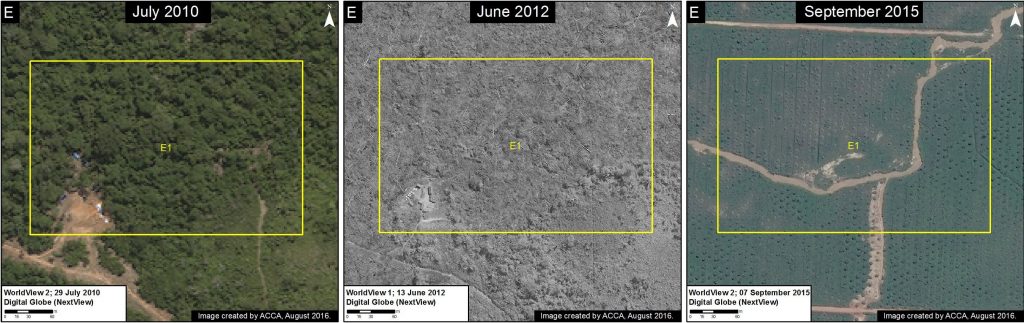

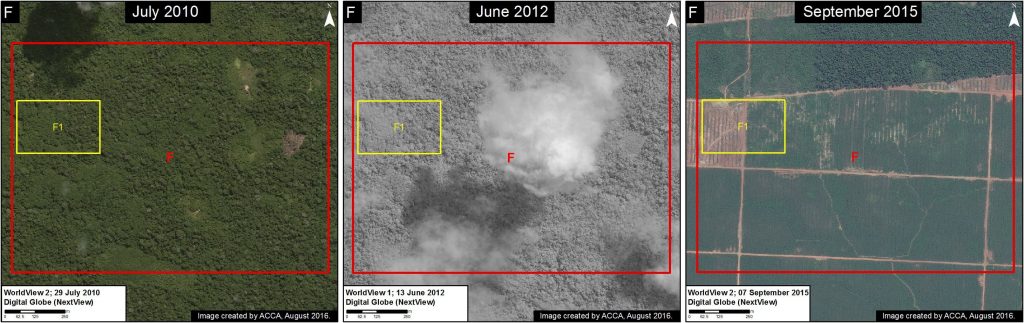

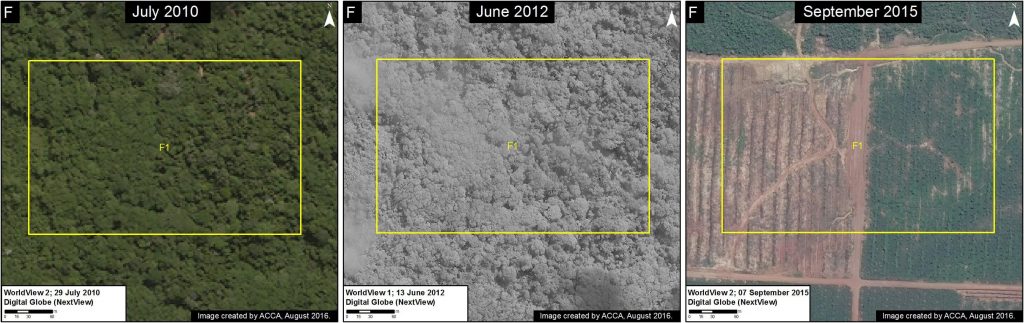

To better understand the deforestation in question, we compare three high-resolution satellite images: 1) July 2010, the most recent high-resolution, color image prior to the start of large-scale deforestation in May 2012; 2) June 2012, a black and white image from the time period when large-scale deforestation began; 3) September 2015, color image showing the established oil palm plantation.

Image 41a shows a base map of the project area in July 2010 (left panel), June 2012 (center panel), and September 2015 (right panel). We indicate areas of primary forest and secondary vegetation,2 recently deforested areas, and oil palm plantation. The images show that large-scale deforestation had begun by June 2012, and by 2015 there was a complete transformation of primary forest and secondary vegetation to large-scale oil palm plantation. Insets A-F show the areas detailed in the zooms below. Click on images to enlarge.

[separator] Zoom A: Primary Forest

Images 41b-i show the zooms of the areas (Insets A – D) in which installation of the oil palm plantation replaced primary forest. The images show primary forest in July 2010 (left panel) and June 2012 (center panel) replaced by oil palm plantation in September 2015 (right panel). Note that in Inset D (Images 41h-i), recently cleared trees can seen as the large-scale deforestation was just starting at that time3.

Zoom B: Primary Forest

Zoom C: Primary Forest

Zoom D: Primary Forest

Zoom E: Secondary Vegetation

Images 41j-m show the zooms of the areas (Insets E – F) in which the oil palm plantation replaced secondary vegetation. The images show secondary vegetation in July 2010 (left panel) and June 2012 (center panel) replaced by oil palm plantation in September 2015 (right panel).

Zoom F: Secondary Vegetation

Notes

1 We define primary forest as an area that, from the first available Landsat image (in this case 1990), was characterized by a forest cover of closed and dense canopy. This definition is consistent with the official definition of the new Forest Law: “Forest with original vegetation characterized by the abundance of mature trees with superior or dominant species canopy, which has evolved naturally.”

2 Primary and secondary forest classifications come from the analysis published in MAAP #4

3 Analysis of additional satellite imagery reveals that the large-scale clearing started between May and June 2012.

Citation

Finer M, Cruz C, Novoa S (2016) Confirming Deforestation for Oil Palm by the company Plantations of Pucallpa. MAAP: 41

From the field: Discovering sustainable livelihoods deep in the Amazon

Ryan Thompson, an Environmental Conservation Master’s of Science Candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, recently returned home from spending 10 weeks in the Peruvian Amazon, going to parts of the rainforest where few people have ever set foot.

He took the trip to produce a series of short videos featuring our partners on the ground who are engaged in forest-friendly enterprises such as fish farming and agroforestry, along ACA’s Manu-Tambopata Conservation Corridor (MAT). Our MAT corridor strategy consists of over 500,000 acres of rainforest in one of the most biologically diverse regions in the world, widely recognized as a global conservation priority. Through a variety of conservation tools including protected areas and sustainable livelihoods activities, the MAT corridor helps protect this keystone habitat, which provides critical ecosystem services such as regulating the climate for the Amazon basin, storing globally significant levels of carbon, and protecting the headwaters of the Amazon.

Through his expeditions, Ryan was able to experience living in the deep Amazon without the comforts of the modern world; how ACA and our sister organization Conservacion Amazónica-ACCA are helping local communities with sustainable practices like agroforestry; and even a little about the local folklore from the region. One special experience was meeting with an ACA partner, Nemecio Barrientos, and his family. Nemecio manages a fish farm that produces over 17,000 pounds of fish every year, providing his family with a sustainable source of income and food. “This experience has been a great teacher,” said Ryan of his weeks in the rainforest, “forcing me to learn to adapt and work with what we’ve got.”

Check out more of Ryan’s stories from the field on his blog: http://ryandthompson.me/blog/.

Fourth graders helping to save the Amazon!

An inspiring group of fourth graders are showing that at any age it’s possible to come together to help conserve our rainforest!

A fourth grade classroom from Greenacres Elementary School in Bethesda, Maryland were presented with three project ideas to support conservation and sustainable livelihood programs in the Peruvian Amazon. After deliberating among themselves and taking a vote, they chose to support our camera trap program. Camera traps are an automated digital device that takes a flash photo or a sequence of photos whenever an animal triggers an infrared sensor. They play an increasingly crucial role in conservation by enabling scientists to collect photographic evidence of the presence and abundance of elusive species such as jaguars, and document responses to threats such as deforestation, with little disturbance to wildlife.

The project idea came from a long time ACA supporter, Marcia Brown from the Foundations of Success, when she learned that her son’s class was interested in running a fundraising project for a nonprofit organization. She suggested ACA as a beneficiary and the kids were excited to learn about all the ways we protect the Amazon. You too can follow in their footsteps and become a forest protector by making a donation, volunteering your time, or visiting our biological stations!

A big thank you to our little supporters: Fernando Molina, Peter Andersen, Zachary Bernier, Maddie Card, Elijah Chambers, Joshua Cohen, Amber Combs, Caitlin Crain, Henry Dirckx, Jovi Greene, Ella Halsey, Miles Hansen, Lilly Kaufmann, Gelienda Lancaster, Noah Lantor, Pau Maset, Nathaniel Mintzer, Avital Morris, Alexandros Murshed, Jacob Orenstein, Manu Padmanabha, Linda Robinson, Brooke Rosen, Sammy Sandler, Alexia Sandonas, Raya Schein, Nora-Sheetal Shaughnessy, Jack Solovey, Drew Steinman, Elana and Grace Stephens, Graham Storper, Dilan Suleman, Ike Wicht, and Raphael Wolf.

Two more conservation areas established in Peru

Last month we shared the story of Miguel Paredes de Bellota and his family, who, with the help of ACA and our sister organization Conservación Amazónica (ACCA), were able to establish their own conservation area called Santuario de la Verónica after a six year battle. This month we helped finalize the establishment of two more conservation areas in the region!

Fundo Cadena and Machusmiaca II are the names of the new protected conservation area, both of which are private lands owned by local families who made the commitment to have the areas set aside for conservation purposes. Venecio Cutipa, the owner of Machusmiaca II, was excited to share the motivation behind his decision to create a conservation area: “For more than 30 years I have lived in this forest, and I envision a future where my four children can also enjoy what nature has given me. By working the land in a sustainable way and protecting the forest, I can achieve that future for the benefit and well-being of my children.”

Combined, Fundo Cadena and Machusmiaca II represent 139 hectares (about 343 acres) of land that is now safely protected. We are so proud of all these individuals and their families for striving to protect the rainforest. When it comes to conservation, every acre matters!

MAAP #40: Early Warning Deforestation Alerts in The Peruvian Amazon

GLAD alerts are a powerful new tool to monitor forest loss in the Peruvian Amazon in near real-time. This early warning system, created by the GLAD (Global Land Analysis and Discovery) laboratory at the University of Maryland and supported by Global Forest Watch, was launched in March 2016 as the first Landsat-based (30-meter resolution) forest loss alert system (previous systems were based on lower-resolution imagery). The alerts are updated weekly and can be accessed through Global Forest Watch (Image 40a, left panel) or GeoBosques (Image 40a, right panel), a web portal operated by the Peruvian Ministry of Environment.

In MAAP, we often combine these alerts with analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery (courtesy of the Planet Ambassador Program and Digital Globe NextView service) to better understand patterns and drivers of deforestation in near real-time. In this article, we highlight 3 examples of this type of innovative analysis from across the Peruvian Amazon:

Example 1: Logging Roads in central Peru (Ucayali)

Example 2: Invasion of Ecotourism Concessions in southern Peru (Madre de Dios)

Example 3: Buffer Zone of Cordillera Azul National Park (Loreto)

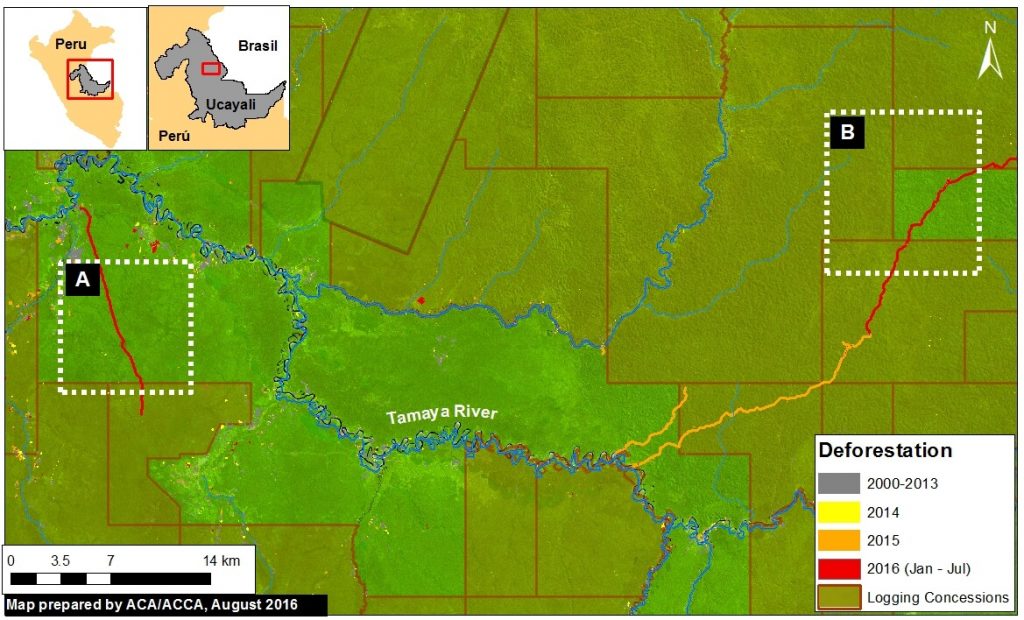

Example 1: Logging Roads in central Peru (Ucayali)

In the previous MAAP #18, we documented the proliferation of logging roads in the central Peruvian Amazon during 2015. In recent weeks, we have seen the start of rapid new logging road construction for 2016. Image 40b shows the linear forest loss associated with two new logging roads along the Tamaya river in the remote central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali region). Red indicates the 2016 road construction (35.8 km). Insets A and B indicate the areas shown in the high-resolution zooms below.

The following images show, in high-resolution, the rapid construction of logging roads in 2016. Image 40c shows the construction of 16.1 km between March (left panel) and July (right panel) 2016 in the area indicated by Inset A. Image 40d shows the construction of 19.7 km between June (left panel) and July (right panel) 2016 in the area indicated by Inset B.

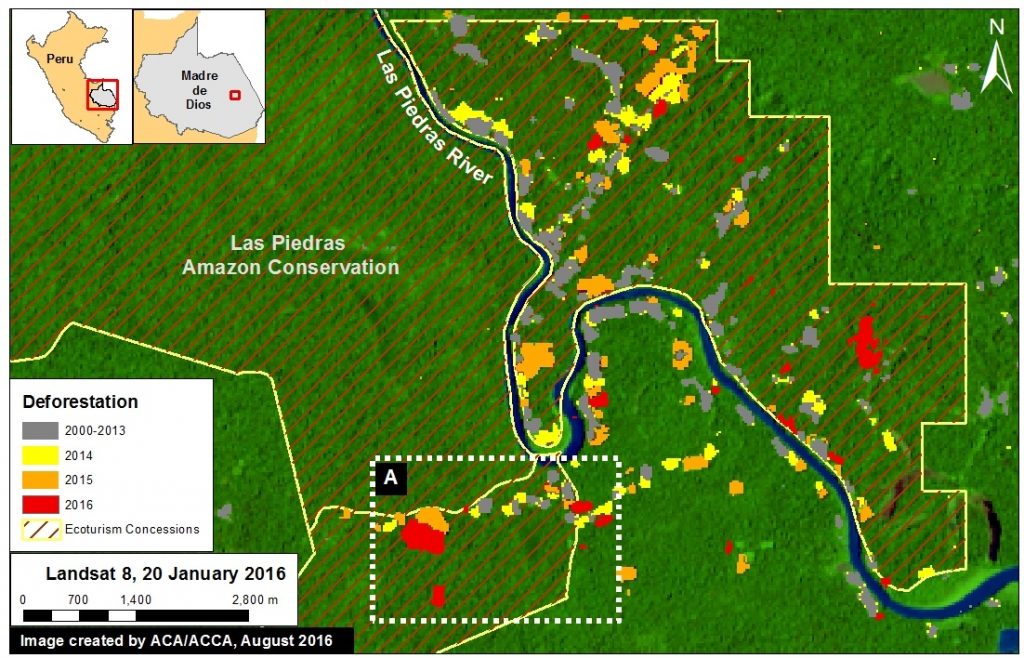

Example 2: Invasion of Ecotourism Concessions in southern Peru (Madre de Dios)

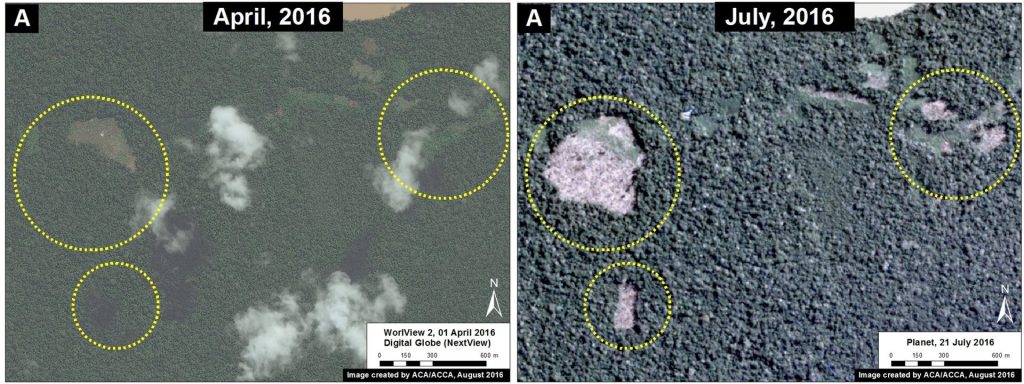

Image 40e shows the recent deforestation within two ecotourism concessions along the Las Piedras River in the Madre de Dios region. Red indicates the 2016 GLAD alerts (67.3 hectares). Note that the Las Piedras Amazon Center (LPAC) Ecotourism Concession represents an effective barrier against deforestation occurring in the surrounding concessions. According to local sources, the main drivers of deforestation in the area are related to the establishment of cacao plantations and cattle pasture (see s MAAP #23). Inset A indicates the areas shown in the high-resolution zoom below.

Image 40f shows high-resolution images of the area indicated by Inset A between April (left panel) and July (right panel) 2016. The yellow circles indicate areas of deforestation between these dates.

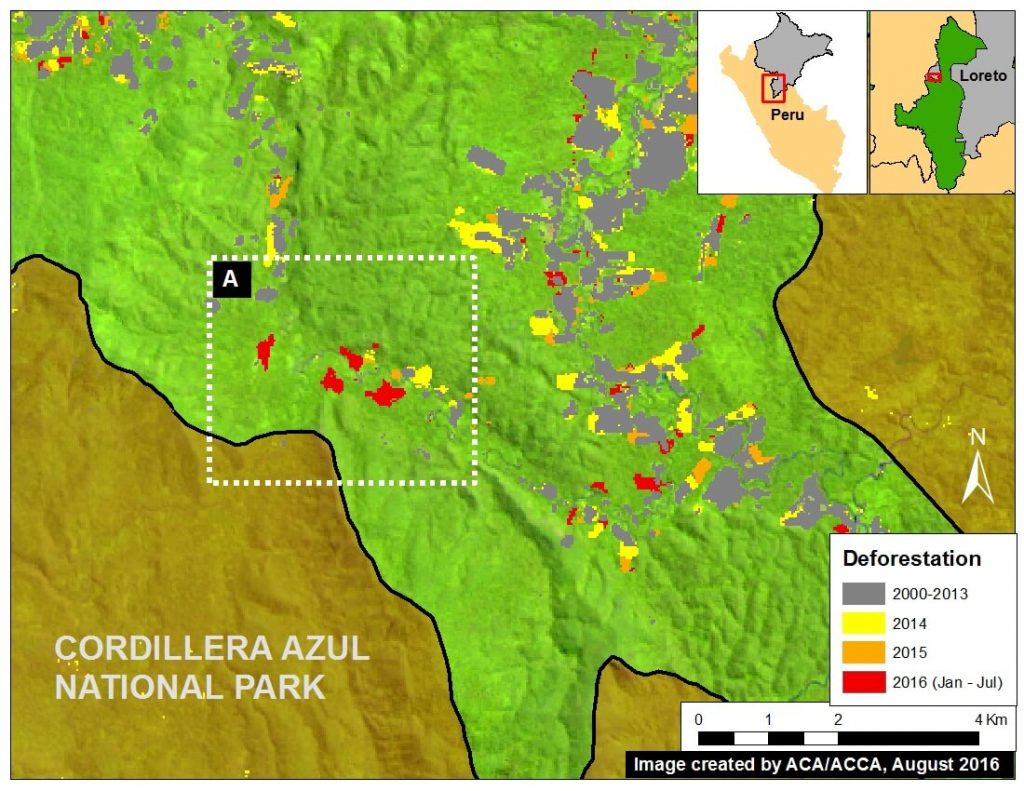

Example 3: Buffer Zone of Cordillera Azul National Park (Loreto)

Image 40g shows the recent deforestation within the western buffer zone of the Cordillera Azul National Park in the Loreto region. Red indicates the 2016 GLAD alerts (87.3 hectares). It is worth noting that this area is classified as Permanent Production Forest, not as an agricultural area.

Image 40h shows high-resolution images of the area indicated by Inset A between December 2015 (left panel), January 2016 (central panel), and July 2016 (right panel). The yellow circles indicate areas that were deforested between these dates. The driver of the deforestation appears to be the establishment of small-scale agricultural plantations.

Citation

Finer M, Novoa S, Goldthwait E (2016) Early Alerts of Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 40.

Loading...

Loading...