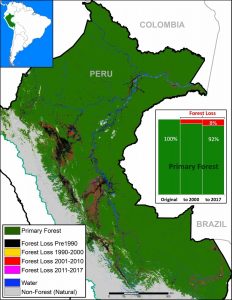

In previous reports, we have documented that oil palm is one of the deforestation drivers in the Peruvian Amazon (MAAP #41, #48). However, the full extent of this sector’s deforestation impact is not well known.

A newly published study assessed the deforestation impacts and risks posed by oil palm expansion in the Peruvian Amazon. Here, we review some of the key findings.

We first present a Base Map of oil palm in the Peruvian Amazon, highlighting the plantations that have caused recent deforestation. We then show two zooms of the most important oil palm areas, located in the central and northern Peruvian Amazon, respectively.

In summary, we document over 86,600 hectares (214,000 acres) of oil palm, of which we have confirmed the deforestation of at least 31,500 hectares for new plantations (equivalent to nearly 59,000 American football fields).

In other words, yes oil palm does cause Amazon deforestation, but not nearly as much as Asia.

Loading...

Loading...