Long, daily hikes in the forest always reveal remarkable events in nature, which could be easily overlooked if not for our curiosity for nature and its complexity. The Los Amigos Bird Observatory (LABO) is currently studying the ecology of the 11 sympatric tinamou that cohabit the forest at our Los Amigos birding lodge.

Uncategorized

Global Big Day is just around the corner! Let’s break a record!

Global Big Day is May 5, and our teams of birders are ready to break records at our lodges in Peru! Besides being birding’s biggest day worldwide, for us, it represents a unique opportunity to raise awareness about the astounding bird diversity found in Peru and at our birding lodges, and the importance of their conservation.

Bird Migration in the Amazon basin

The migration of animals is one of the most studied phenomena by scientists, and one of the most anticipated events by nature lovers. This annual phenomenon, which is affected by many factors such as age, sex, resistance, and survival skills, involves animals leaving habitats in winter and reaching the ideal and warmest places for feeding and reproduction. Birds — with their ability to fly, a highly developed nervous system and a physiology that responds quickly to changes – use the changing seasons to their advantage, some traveling thousands of miles in search of habitats with the greatest amount of resources. The birds that arrive in South America from other regions are called neotropical migrants and studying exactly how and why these species move is one of the biggest challenges for researchers to understand.

Neotropical migrants nest in temperate zones of the continent and during the winter they move towards or within the Amazon, and are called either boreal migrants (coming from the north) or austral (coming from the south). Knowing this crucial detail is key for implementing future conservation efforts, as it tells us which habitats need to be protected for birds to be able to migrate.

Amazon Conservation directly protects nearly 10,000 acres of forest at Wayqecha and Villa Carmen, two of its three birding lodges located on the eastern slope of the Peruvian Andes. The pristine cloud forest and premontane forest habitats found there are threatened by agricultural expansion, illegal logging, and climate change. There are currently 32 species of migratory birds found at our lodges, with Villa Carmen topping the list with a whopping 26 species, including 11 boreal migrants (such as Barn Swallow, Olive-sided Flycatcher, Western Wood-Pewee, Sulphur Bellied Flycatcher, and even an Upland Sandpiper, which travels over 6,000 miles every year to reach South America) and 15 austral species. Wayqecha has 6 boreal species, including the Blackburnian Warbler during the months of September to April, who trades the coniferous forests of the northern hemisphere for the cloud forests of South America, traveling over 5,000 miles, and only at night. You can also see the Golden-winged Warbler, Swainson’s Thrush and Broad-winged Hawk.

Amazon Conservation directly protects nearly 10,000 acres of forest at Wayqecha and Villa Carmen, two of its three birding lodges located on the eastern slope of the Peruvian Andes. The pristine cloud forest and premontane forest habitats found there are threatened by agricultural expansion, illegal logging, and climate change. There are currently 32 species of migratory birds found at our lodges, with Villa Carmen topping the list with a whopping 26 species, including 11 boreal migrants (such as Barn Swallow, Olive-sided Flycatcher, Western Wood-Pewee, Sulphur Bellied Flycatcher, and even an Upland Sandpiper, which travels over 6,000 miles every year to reach South America) and 15 austral species. Wayqecha has 6 boreal species, including the Blackburnian Warbler during the months of September to April, who trades the coniferous forests of the northern hemisphere for the cloud forests of South America, traveling over 5,000 miles, and only at night. You can also see the Golden-winged Warbler, Swainson’s Thrush and Broad-winged Hawk.

Extensive trails at each lodge take you deep into the forest, making it possible to observe these friendly “guests.” By conserving these forests, we are protecting bird diversity not only in the Amazon, but across continents.

– Javier Farfán, Biologist, and Science Coordinator at Wayqecha Cloud Forest Birding Lodge

– Javier Farfán, Biologist, and Science Coordinator at Wayqecha Cloud Forest Birding Lodge

The Biggest “Big Day” for Los Amigos Bird Observatory

The Global Big Day (GBD) is getting closer, and besides being the birding’s biggest day worldwide, where thousands of birders get together to celebrate birds for 24 hours straight, it is also a means to improve human’s commitment to conserving these species. For us, it represents a unique opportunity to admire and spread awareness of the importance of maintaining the astounding bird diversity found at Los Amigos. Birding is one of the most exciting experiences for anyone who has a passion for birds, but is particularly challenging throughout the densely foliated and dark forest typical of lowland Amazonia, where bird vocalization is key to identify species. We here at Los Amigos are incredibly excited about our upcoming GBD, and did not want to miss this opportunity to share some of our previous experience of Los Amigos Big Days!

On May 9 of 2015, Peru beat the world record and conquered the precious first place of birds with 1188 species registered, followed by Brazil, and Colombia. This not only reaffirmed Peru’s unique avian diversity but also revealed Peru’s potential for birdwatching as an important ecotourism activity. On that day, Peru as a country was not the only area making history on avian records; Los Amigos itself was positioned in nothing less than the fifth place at the global level, with 308 bird species! In July of that same year, Sean Williams, an avian researcher, did his own Big Day after a friaje, a massive cold front that comes from the Antartic winds and hits the Amazon. After several field seasons spent at Los Amigos, Sean was able not only to become highly familiar with the avifauna by recognizing the songs, and even locations and nests of rare birds. July 23rd became one Sean’s biggest big days, and after an exhaustive 19 hours and 11 miles of complete immersion into the calls and colorful flying displays across forest strata, Sean registered 345 species! Sean’s Big Day is imprinted in his memory, highlighting his eternal passion for the Amazon and its birds.

On May 9 of 2015, Peru beat the world record and conquered the precious first place of birds with 1188 species registered, followed by Brazil, and Colombia. This not only reaffirmed Peru’s unique avian diversity but also revealed Peru’s potential for birdwatching as an important ecotourism activity. On that day, Peru as a country was not the only area making history on avian records; Los Amigos itself was positioned in nothing less than the fifth place at the global level, with 308 bird species! In July of that same year, Sean Williams, an avian researcher, did his own Big Day after a friaje, a massive cold front that comes from the Antartic winds and hits the Amazon. After several field seasons spent at Los Amigos, Sean was able not only to become highly familiar with the avifauna by recognizing the songs, and even locations and nests of rare birds. July 23rd became one Sean’s biggest big days, and after an exhaustive 19 hours and 11 miles of complete immersion into the calls and colorful flying displays across forest strata, Sean registered 345 species! Sean’s Big Day is imprinted in his memory, highlighting his eternal passion for the Amazon and its birds.

Undoubtedly, Los Amigos avifauna is vast, and besides just walking miles and miles during a Big Day, it is important to create a strategic plan to experience it. Last summer, Alex Wiebe, a young ornithologist but incredibly knowledgeable about Neotropical avifauna, came last year to Los Amigos, and did his big day registering 250 bird species throughout the day, covering all the different types of habitats. In doing so, endemics and charismatic birds such as the Rufous-fronted anthrush, Ihering’s antwren, Long-crested pygmy tyrant, Black-faced cotinga, Peruvian recurvebill, Manu parrotlet, Pavonine quetzal, Blue-headed macaws, Rufous-vented ground cuckoo, Spangled and Plum-throated cotinga can be just a few of the names marked on your checklist.

Undoubtedly, Los Amigos avifauna is vast, and besides just walking miles and miles during a Big Day, it is important to create a strategic plan to experience it. Last summer, Alex Wiebe, a young ornithologist but incredibly knowledgeable about Neotropical avifauna, came last year to Los Amigos, and did his big day registering 250 bird species throughout the day, covering all the different types of habitats. In doing so, endemics and charismatic birds such as the Rufous-fronted anthrush, Ihering’s antwren, Long-crested pygmy tyrant, Black-faced cotinga, Peruvian recurvebill, Manu parrotlet, Pavonine quetzal, Blue-headed macaws, Rufous-vented ground cuckoo, Spangled and Plum-throated cotinga can be just a few of the names marked on your checklist.

This year, Los Amigos Bird Observatory is ready for the GBD with a team led by birding experts that will be searching for the nearly 600 bird species throughout the mosaic landscape of Los Amigos! The team is comprised of: Fernando Angulo, avian researcher of CORBIDI and LABO Advisory member; Alex Wiebe, Franzen Fellow, and student of Cornell University; and Rolin Flores, an indigenous bird guide from the community of Diamante around Manu National Park with vast birding experience in the Manu region. All the memorable Big Days records at Los Amigos have taken our breath away and demonstrated that the efforts of preserving this mesmerizing forest and its surroundings are visible in the wildlife and avifauna thriving in Los Amigos, our home.

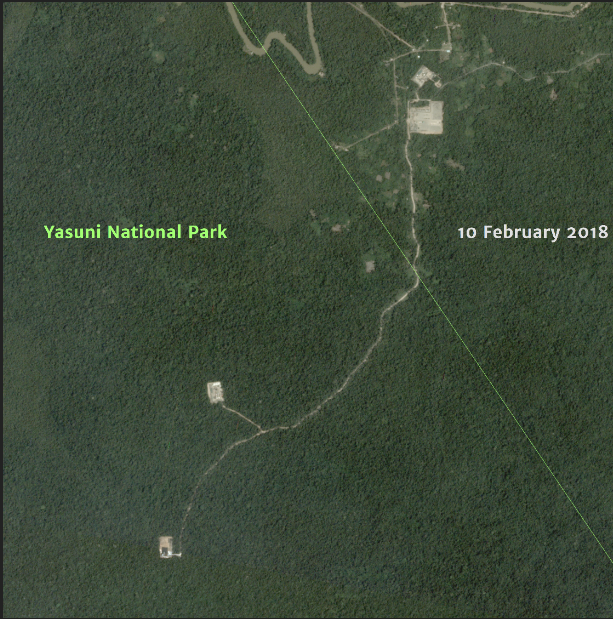

MAAP # 82: Oil-Related Deforestation in Yasuni National Park, Ecuadorian Amazon

Yasuni National Park, located in the heart of the Ecuadorian Amazon, is arguably the most biodiverse area in the world.

It is also the ancestral territory of the Waorani, and their relatives in voluntary isolation.

However, underneath the park are large oil fields, setting up the constant conflict looming over Yasuni. In fact, in a recent referendum, Ecuadorian voters approved limiting the oil extraction area within Yasuni National Park to 300 hectares (740 acres).

Here, we analyze high-resolution satellite imagery to estimate both direct and indirect oil-related deforestation within Yasuní National Park.

For direct impact, we document the deforestation of 169 hectares (418 acres) within the park for oil-related infrastructure.

For indirect impact, we document the deforestation of 248 hectares (613 acres) due to colonization along an oil access road.

The total direct and indirect deforestation due to oil extraction is 417 hectares (1,030 acres).

Thus, one could argue that the oil-related deforestation has already exceeded the 300 hectares (740 acres) approved by the voters.

We illustrate these results in a Story Map.

MAAP #82: Oil-related Deforestation in Yasuni National Park, Ecuadorian Amazon

https://maaproject.org/yasuni_eng/

Birds of Prey: Neotropical monkeys’ most fearsome predators

Jaguars are without a doubt the top predators in Amazonia, but organisms flying above the canopy certainly have a big advantage and unique predation skills that make them respectable predators when compared to wild cats. Raptors are considered the major predators of new world primates, such as crested eagles (Morphnus guianensis) predation on infant tamarins (Leontocebus mystax & L. fuscicollis) and also squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus); black-hawk eagles are also known to attack howler monkeys; and the largest and powerful harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) predation on saki, capuchin and night monkeys. Current ecological knowledge of Neotropical raptors is scarce, thus filling in the gaps of information on this particular group of birds will allow us to understand their ecology and general biology, whether it is through anecdotal incidents or observations in the field.

Photo by Marc Fasol

The black-and-white hawk eagle (Spizaetus melanoleucus) is one of the 55 birds of prey found at Los Amigos. Compared to other well-known raptors such as the mighty harpy eagle or the crested eagle, the black-and-white hawk eagle is a small size bird (body mass: 780-1191 g; wingspan: 110-135 cm), feeding mainly on terrestrial and arboreal birds such as tinamous and guans, and some documents report small mammals and reptiles in their diet. However, successful predation on primates by this species was not described until 2014, when a group of researchers witnessed and described the mortal attack of the Rylands’ bald-faced saki monkey (Pithecia rylandsi) at Los Amigos.

This fatal event was recorded on 23 July, 2014, during a long-term project assessing the anti-predation behavior and alarm calling of P. rylandsi at Los Amigos. While conducting the usual primate behavior monitoring, one of the research assistants heard a large bird flapping, followed by alarming calls of a group of sakis, which are whistle-like calls emitted when they detect an eagle’s presence. Upon the researcher’s return after a couple of hours, he heard wing’s flapping in the same location. After following the motion event, the researcher found out the black-and-white hawk eagle feeding on an adult saki’s carcass on the ground. The black-and-white hawk quickly flew away after detecting the researcher approaching. Most of the saki’s flesh, muscles and skin were removed, with fur scattered beside and along a 16.4 m path away from the carcass. Several puncture holes were noted on the body and skull, while the stomach lay untouched next to the body despite most of the soft tissue having been removed. Although the observers didn’t visually witness the attack, the described observations together with the physical injuries documented on the saki most likely indicate that it was the black-and-white hawk-eagle as its predator.

Black-and-white hawk eagles utilize the “soar and stoop” hunting tactic, compared to the “perch and wait” strategy used by large raptors, consisting of searching for preys above the canopy and forest edges and, upon prey detection, diving rapidly into the forest to attack them. This report suggested that smaller and lesser-known raptors, like the black-and-white hawk eagle, should also be considered important predators of Neotropical primates, principally those that occupy the mid to upper canopy given their hunting strategy. Identifying and providing evidence of predation events like this is key to learn more about less prominent raptors, so keep your eyes and ears open while walking in the forest!

For more references:

Adams, D., Williams, S. 2017. Fatal attack on a Ryland’s bald-faced saki monkey (Pithecia rylandsi) by a black-and-white hawk eagle (Spizaetus melanoleucus). Primates 58: 361-365.

Robinson, S. 1994. Habitat selection and foraging ecology of raptors in Amazonian Peru. Biotropica 26(4): 443-458.

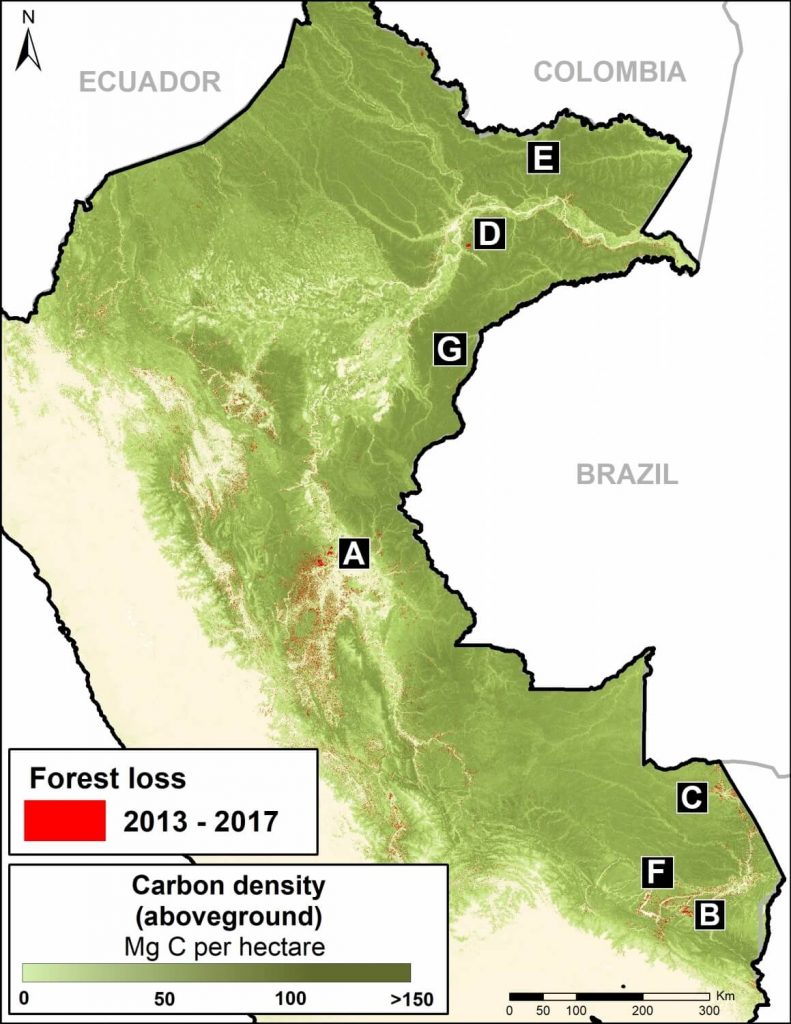

MAAP #81: Carbon loss from deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon

When tropical forests are cleared, the enormous amount of carbon stored in the trees is released to the atmosphere, making it a major source of global greenhouse gas emissions (CO2) that drive climate change.

In fact, a recent study revealed that deforestation and degradation are turning tropical forests into a new net carbon source for the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change.1

The Amazon is the world’s largest tropical forest, and Peru is a key piece of that. Researchers (led by Greg Asner at the Carnegie Institution for Science) recently published the first high-resolution estimate of aboveground carbon in the Peruvian Amazon, documenting 6.83 billion metric tons.2

Here, we analyze this same dataset to estimate the total carbon emissions from deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon between 2013 and 2017. We estimate the loss of 59 million metric tons of carbon during these last five years, the equivalent of around 4% of annual United States fossil fuel emissions.3

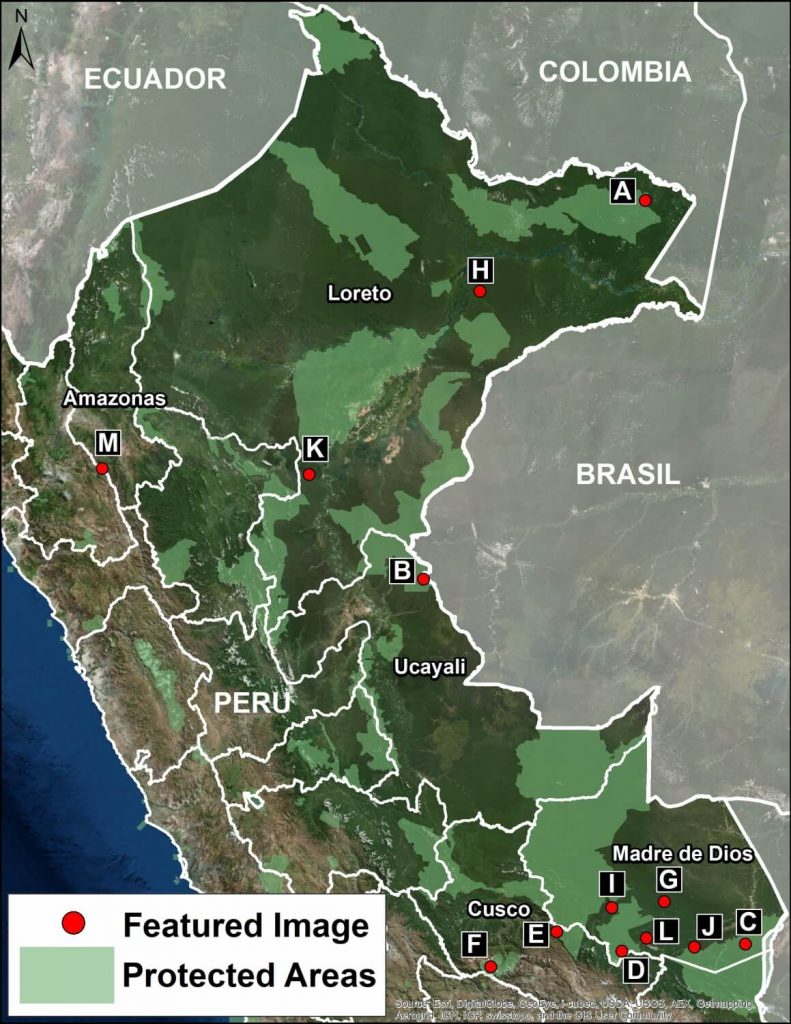

We present a series of zoom images to show how carbon loss happened in several key areas impacted by the major deforestation drivers: gold mining, large-scale oil palm and cacao plantations, and smaller-scale agriculture. The labels A-G correspond to the zooms below.

We also show how protected areas are protecting hundreds of millions of metric tons of carbon in some of the most important areas in the country.

On the positive side, having this detailed information may provide added incentives to slow deforestation and degradation as part of critical climate change strategies.

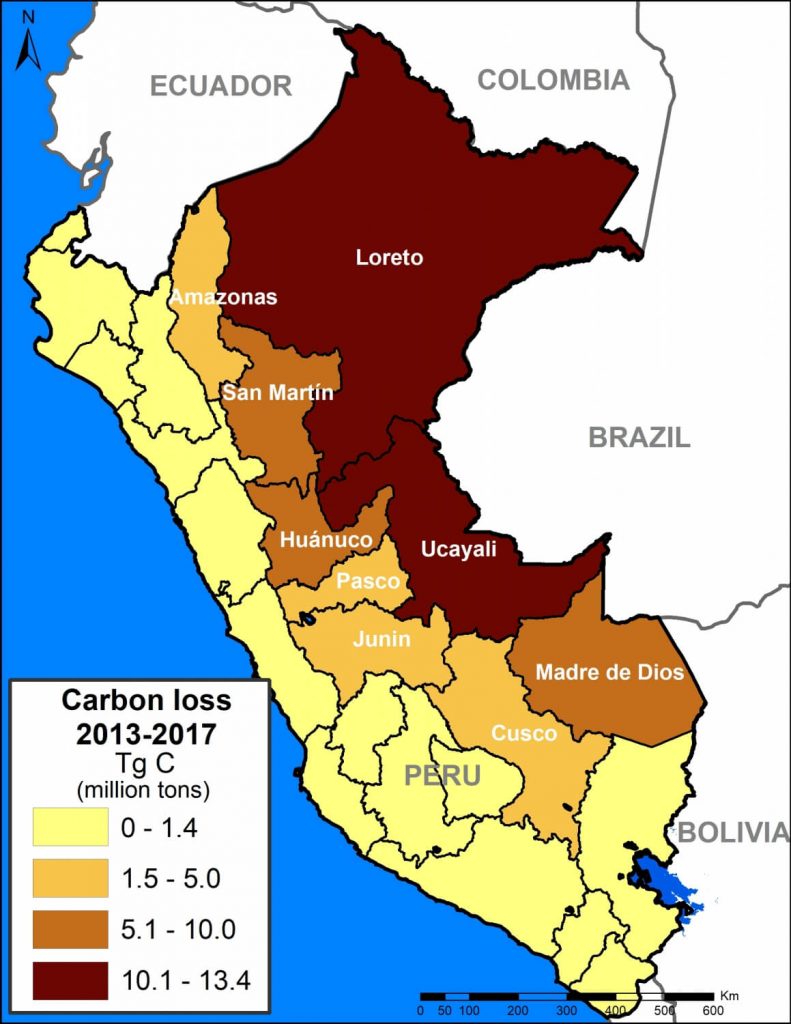

Major Findings

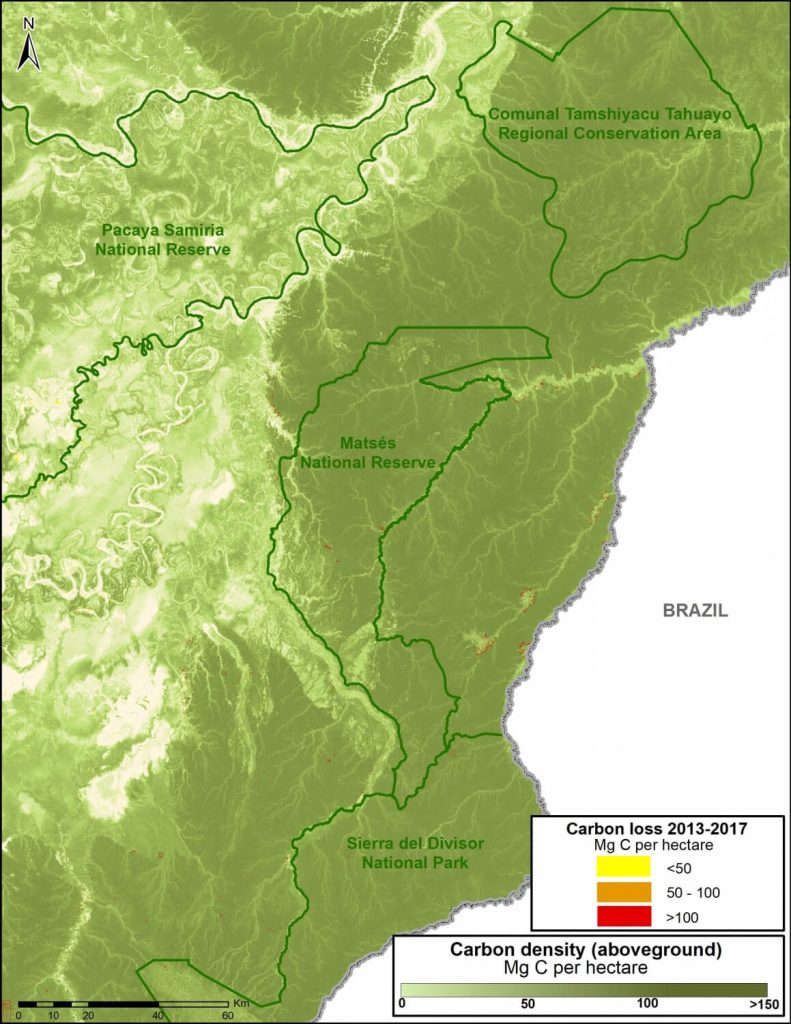

The base map (see above) shows, in shades of green, carbon densities across Peru. It also shows, in red, the forest loss layer from 2013 to 2017.

We calculated the estimated amount of carbon emissions from forest loss during these five years: 59.029 teragrams, or 59 million metric tons.

The regions with the most carbon loss are 1) Loreto (13.4 million metric tons), 2) Ucayali (13.2 million), 3) Huánuco (7.3 million), 4) Madre de Dios (7 million), and 5) San Martin (6.9 million).

These values include some natural forest loss. Overall, however, they should be considered underestimates because they do not include forest degradation (for example, selective logging).

A recent study revealed that degradation may account for 70% of emissions, thus total carbon emissions from forests in the Peruvian Amazon may be closer to 200 million metric tons.

Next, we show a series of zoom images to show how carbon loss happened in several key areas. We also show how protected areas and conservation concessions are protecting the most important carbon reserves.

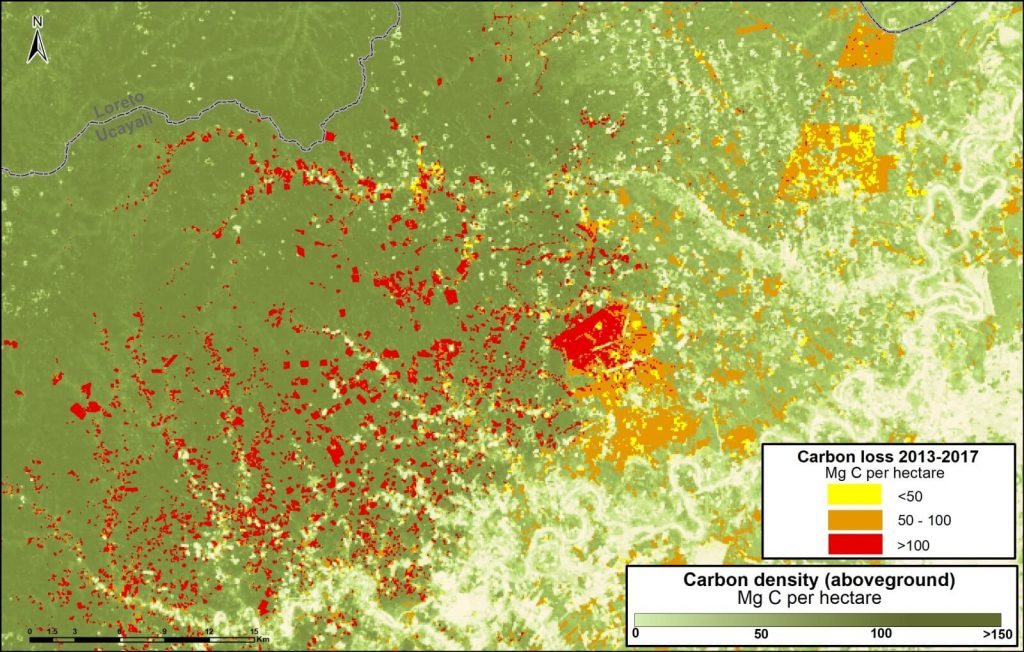

Zoom A: Central Peruvian Amazon

Image A shows the loss of 2.8 million metric tons of carbon in a section of the central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali region). On the east side of image, note the loss due to two large-scale oil palm plantations (649,000 metric tons); on the west side, note small-scale agriculture penetrating deeper into high carbon density forest.

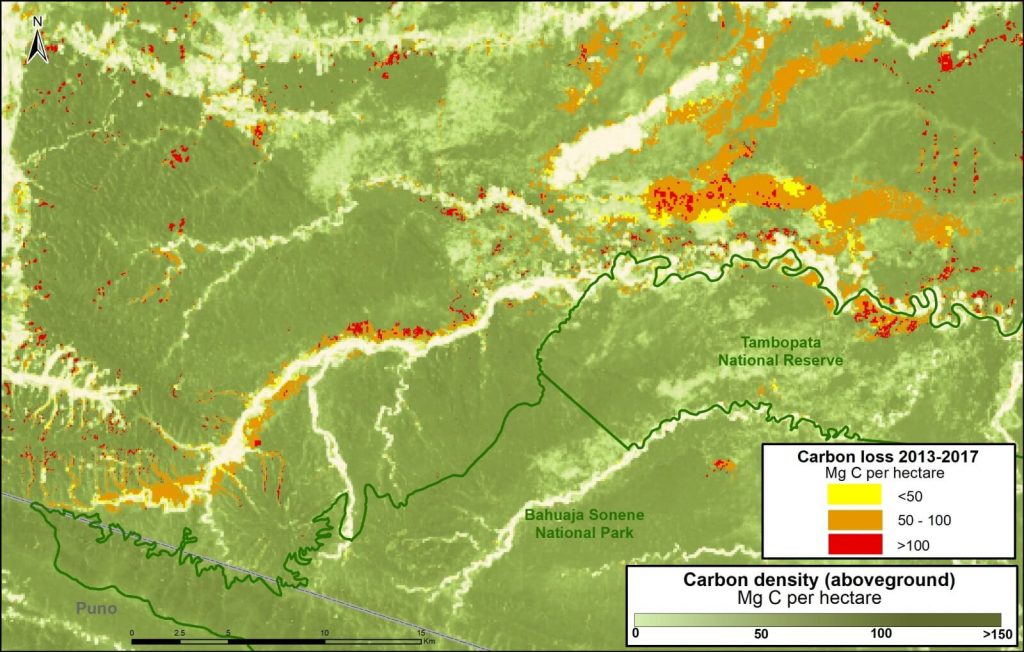

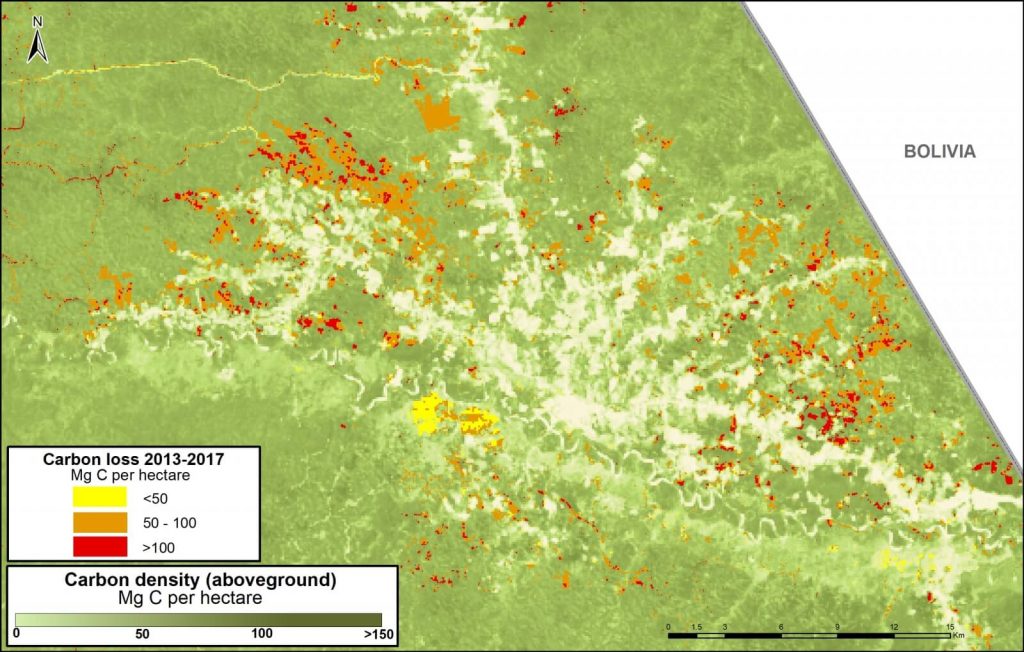

Zoom B: Southern Peruvian Amazon (gold mining)

Image B shows the loss of 756 thousand metric tons of carbon due to gold mining in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region). On the east side of image is the sector known as La Pampa; west side is Upper Malinowski.

Zoom C: Southern Peruvian Amazon (agriculture)

Image C shows the loss of 876 thousand metric tons of carbon in the southern Peruvian Amazon around the town of Iberia (Madre de Dios region). Note the expanding carbon loss along both sides of the Interoceanic Highway that crosses the image.

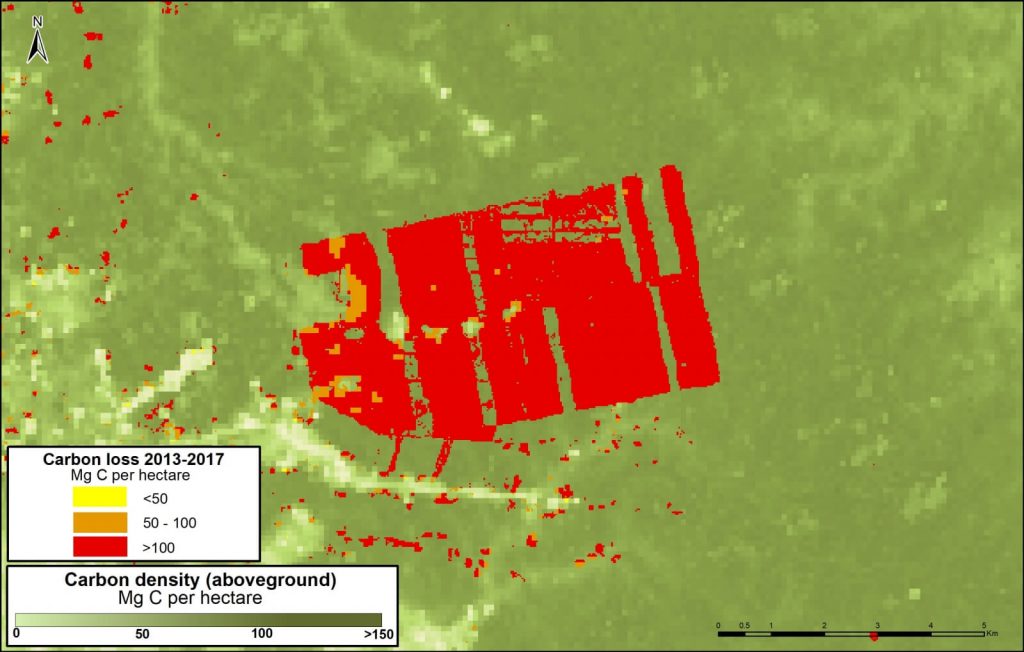

Zoom D: United Cacao

Image D shows the loss of 291 thousand metric tons of carbon for a large-scale cacao project (United Cacao) in the northern Peruvian Amazon (Loreto region). Note that nearly all the forest clearing occurred in high carbon density forest. This is another line of evidence that the company cleared primary forest, contrary to their claims that the area was already degraded.

Zoom E: Yaguas National Park

Image E shows how three protected areas, including the new Yaguas National Park, are effectively safeguarding 202 million metric tons of carbon in the northeastern Peruvian Amazon. This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

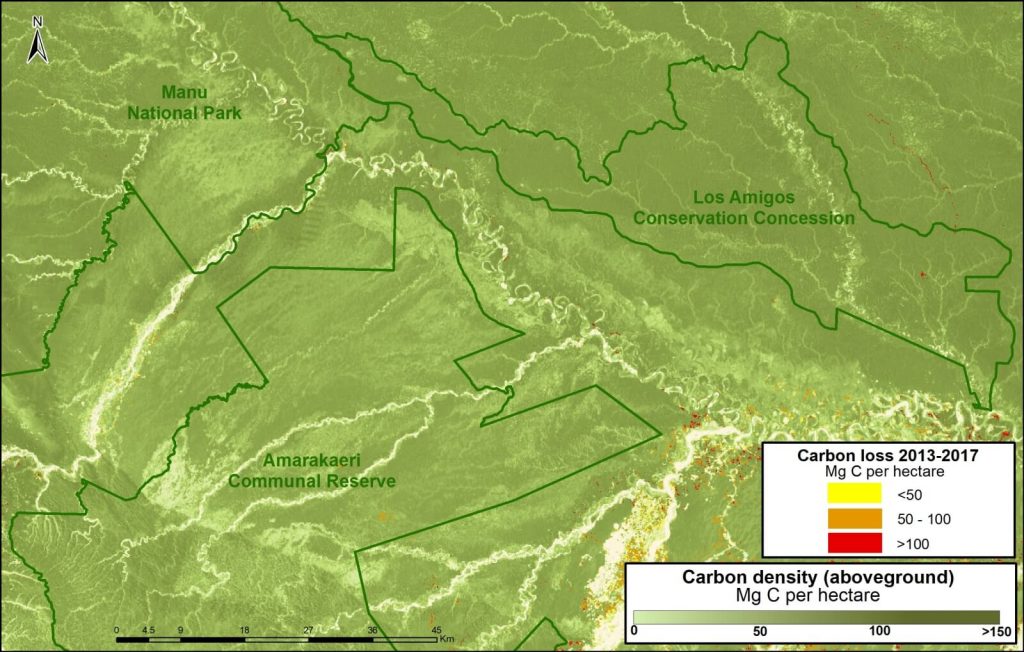

Zoom F: Los Amigos Conservation Concession

Image F shows how Los Amigos, the world’s first conservation concession, is effectively safeguarding 15 million metric tons of carbon in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Two surrounding protected areas, Manu National Park and Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, safeguard an additional 194 million metric tons. This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

Zoom G: Sierra del Divisor National Park

Image G shows how three protected areas, including the new Sierra del Divisor National Park, are effectively safeguarding 270 million metric tons of carbon in the eastern Peruvian Amazon.

This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

Methodology

Para el análisis se utilizó los datos de carbono sobre el suelo generados por Asner et al 2014, y los datos de pérdida de bosques identificados por el Programa Nacional de Conservación de Bosques (PNBC-MINAM) de los años 2013 al 2016 así como las alertas tempranas del año 2017. Primero uniformizamos los datos de pérdida de bosque 2013-2016 con las alertas tempranas del año 2017 para evitar superposición y tener un solo dato 2013-2017. Posteriormente, extraemos los datos de carbono de las áreas de pérdida de bosque del 2013-2017, este proceso permitió obtener la densidad de carbono (por hectárea) en relación al área de la pérdida de bosque para finalmente estimar el total de stocks de carbono perdido entre el año 2013 al 2017.

References

1 Baccini A, Walker W, Carvalho L, Farina M, Sulla-Menashe D, Houghton RA (2017) Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science. 13;358(6360):230-4.

2 Asner GP et al (2014). The High-Resolution Carbon Geography of Perú. Carnegie Institution for Science.

3 Boden TA, Andres RJ, Marland G (2017) National CO2 Emissions from Fossil-Fuel Burning, Cement Manufacture, and Gas Flaring: 1751-2014. DOI 10.3334/CDIAC/00001_V2017

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2017). Carbon loss from deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 81.

There is no song copyright in the birdcall industry

Even if it is your first time in the Amazon forest or you are lucky enough to live and enjoy a green heaven like it, you will be enchanted by its colors, the moist aroma of rain falling on the low nutrient Amazonian soil, as well as a chorus of melodies displaying harmonic rhythm, from low to high pitch sounds, music that represents breath, words, and life. These last three representations could not better describe the importance of animal vocalization in a tropical rainforest. Among birds, specifically, this is a critical way they communicate among one another in competition for mates and territories.

Hypocnemis peruviana (male) by Joe Tobias

Inability to differentiate vocal signals within and between species could lead to unnecessary territorial aggression, negative impacts on a species reproductive success (i.e. unfit hybrids), and overall fitness. Therefore it is expected that birdsongs are specific for every species, particularly in dense forests like Amazonia, where vocal signals are more valuable and efficient than visual cues. So, is it possible for two sympatric bird species (not closely related) to sing the same songs?

The answer is YES! Research conducted by LABO Advisory group members at Los Amigos in 2008, Professor J. Tobias and N. Seddon, found that two Neotropical antbirds species have almost identical songs, making this the first evidence demonstrating that convergent evolution (i.e. organisms of different lineages evolving similar traits) can occur through social interactions between species.

The studied species were two sympatric Hypocnemis antbirds: H. peruviana and H. subflava, which are highly abundant organisms inhabiting the understory of Los Amigos forest. Hypocnemis antbirds are small monogamous passerine birds, and molecular tests have showed that H. peruviana and H. subflava are non-sister species and were split from a common ancestor ~3.4 million years ago. Even though they have been part of different lineages a long time ago, both species share similar foraging behavior, diet, six standard body morphological measurements. However these species do differ in their plumage color (Figure 1 and 2). Moreover, songs in suboscine passerine birds, such as Hypocnemis, are not learned and instead are genetically determined, however this had been challenged by other studies that suggest that vocal learning does lead to song differences in suboscines. Hypocnemis vocalizations play important roles in intrasexual competition, mate attraction and territory defense. From all the characteristics mentioned above, it is assumed that highly territorial organisms must rely on vocal signals specificity to discriminate between species and individuals.

Hypocnemis subflava (male) by Joe Tobias

Dr. Tobias and Dr. Seddon analyzed 343 songs of 96 sympatric individuals (H. subflava and H. peruviana) through acoustic and playback experiments at Los Amigos, and demonstrated that territorial songs in males are more similar than non-territorial signals between both species, not allowing males to discriminate the territorial signals of individuals of the same and different species. The same pattern was found in females. How could this phenomenon be explained? First, even though H. subflava and H. peruviana are partially segregated by habitat, both species interact regularly at territory boundaries, increasing the likelihood of rivalry for space and food. This latter explanation is supported by the fact that both antbirds are not migratory birds and neither move outside their territory. LABO Advisory members suggested that song convergence must be a consequence of selection forces caused by competition between species, which is supported by several studies showing that song matching (i.e. answering with a similar song) is an aggressive display in territory disputes, within and between species!

For more reference:

1. Tobias, J.A. & Seddon, N. (2009). Signal design and perception in Hypocnemis antbirds: Evidence for convergent evolution via social selection. Evolution 63, 3168-3189.

Want to share this blog post with your friends and family? Give them this link.

MAAP #80: Amazon Beauty, in High-Resolution

MAAP tracks the most urgent deforestation cases in the Andean Amazon, thus it can be a bit depressing. However, it is important to remember why we do it: the Amazon is spectacular.

Here, we present a series of high-resolution satellite images to show the incredible beauty of the Peruvian Amazon, and help remind us all why it is so important to protect.

All the images, obtained from DigitalGlobe, are both recent and very high resolution (less than 0.5 meters). Together, they form an art exhibition, starring the forests, rivers, and mountains of the Peruvian Amazon.

The categories of the images are: “Protected Areas” and “Threatened Areas.”

The Protected Areas include National Parks (Yaguas, Sierra del Divisor, and Manu); National Reserve (Tambopata); Communal Reserve (Amarakaeri); and Regional Conservation Area (Choquequirao).

The Threatened Areas include areas at risk due to gold mining, road construction, hydroelectric dams, and new oil palm and cacao plantations.

Click on each image to enlarge. See the base map for the location of each image (A-M).

MAAP #79: Seeing Through the Clouds: Monitoring Deforestation With Radar

MAAP has repeatedly emphasized the power and importance of Earth observation satellites with optical sensors (such as Landsat, Planet, DigitalGlobe).

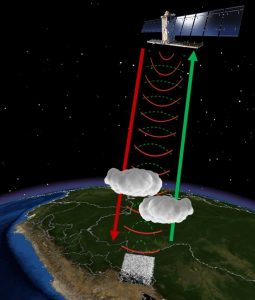

However, they also have a key limitation: clouds block the data about Earth from reaching the sensor, a common problem in rainy regions like the Amazon.

Fortunately, there is another powerful tool with a unique capability: satellites with radar sensors, which emit their own energy that can pass through the clouds (see Image).

Since 2014, the European Space Agency has provided free imagery from its radar satellites, known as Sentinel-1.

In the Peruvian Amazon, for example, Sentinel-1 obtains imagery every 12 days with a resolution of ~20 meters.

Here, we show the power of radar imagery in terms of near real-time deforestation monitoring. We focus on an area with ongoing deforestation due to gold mining in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region).

Loading...

Loading...