In 2019, the Peruvian government launched Operation Mercury to confront the illegal gold mining crisis in the southern Amazonian area known as La Pampa (Madre de Dios region).As a result, deforestation decreased 90% in this critical area (MAAP# 130).

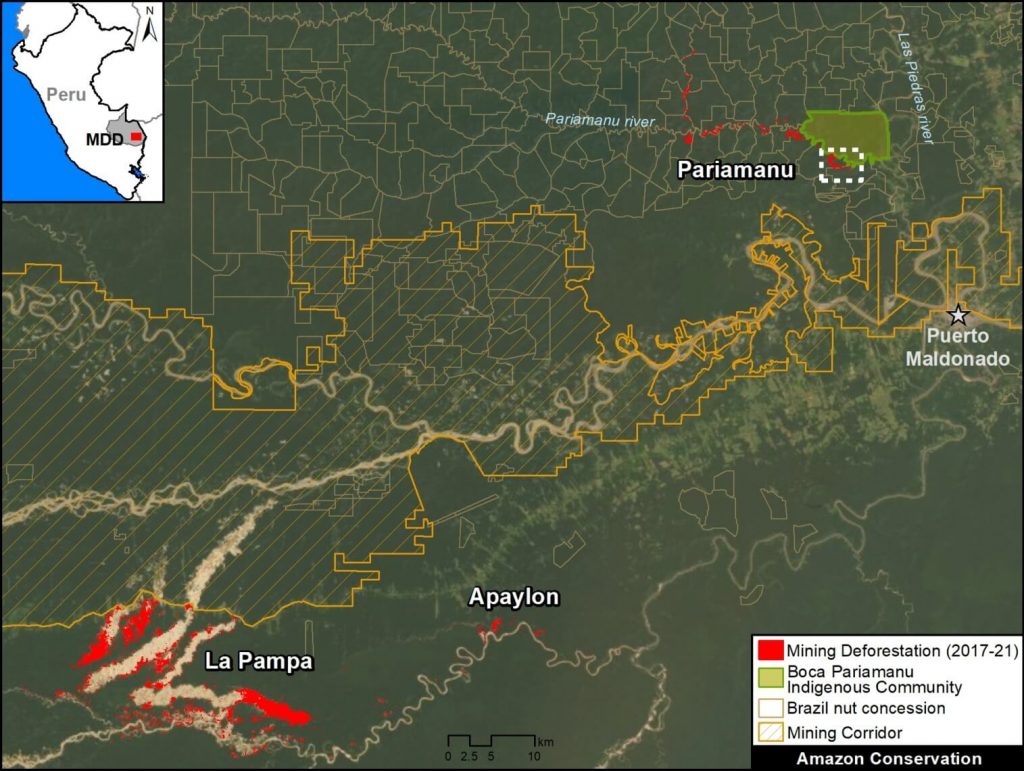

Some illegal gold mining, however, has moved to several new hotspots (Image 1), although at much lower levels.

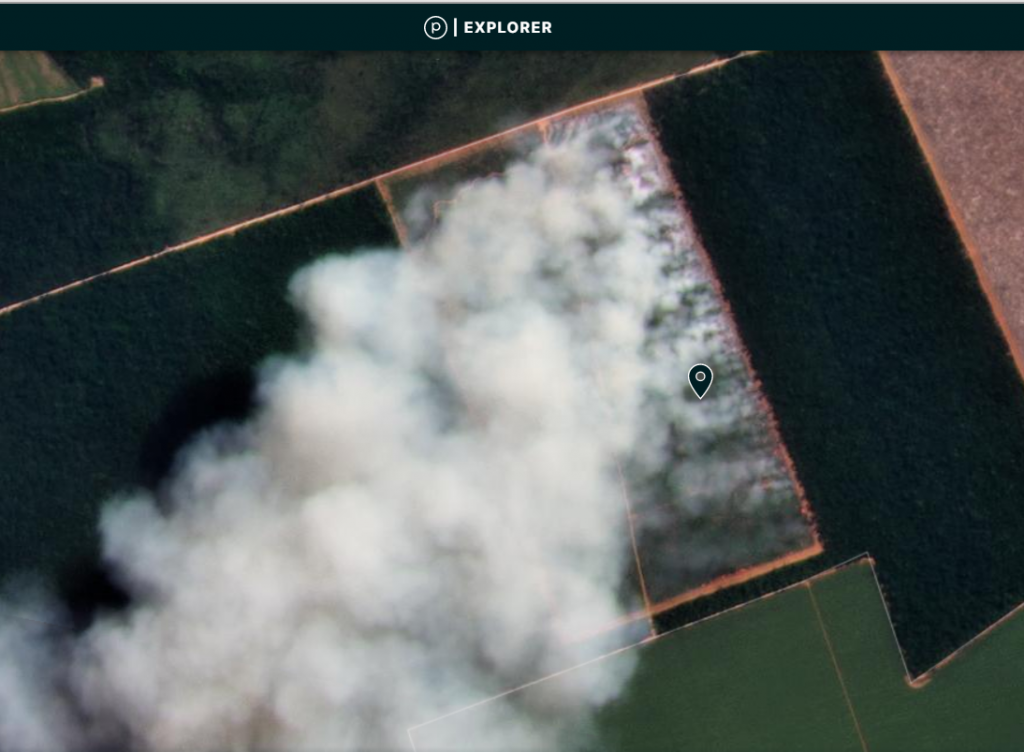

Image 1. Very high-resolution image of the recent gold mining deforestation (10 hectares) in the new hotspot around the Pariamanu river. Data: Planet (Skysat)

The most emblematic hotspot is located along the Pariamanu River, northeast of La Pampa in the Madre de Dios region (see Base Map, below).

We have documented the gold mining deforestation of 204 hectares (504 acres) in the Pariamanu area from 2017 to the present

This mining activity is clearly illegal because it is located within Brazil-nut forestry concessions, and is outside the permitted mining zone (commonly called the “mining corridor”).

Fortunately, a series of timely actions by the Peruvian Government has minimized the irreversible damage along the Pariamanu (see below).

The objective of this report is to present Pariamanu as an emblematic case that links technology with the rapid response action of public entities to address illegal activity in the Amazon.

It also represents a concrete case of strategic collaboration between civil society and the government to try and achieve zero illegal deforestation (and avoided deforestation).

Pariamanu

Base Map

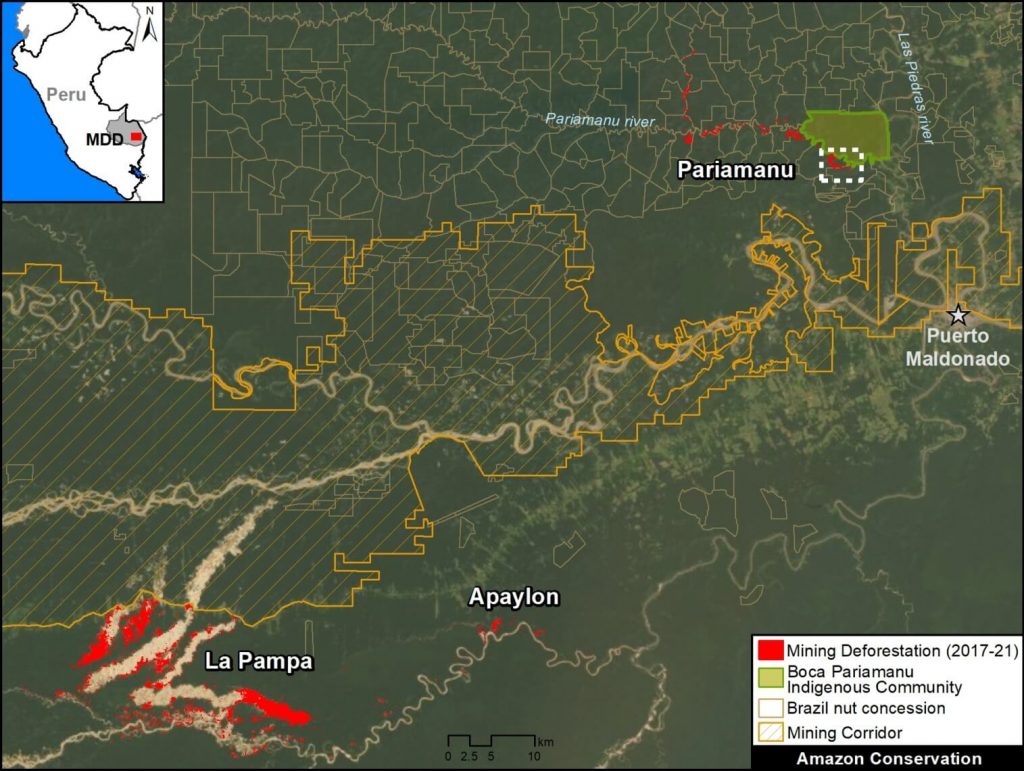

Base Map. Illegal gold mining deforestation along the Pariamanu river, in the context of La Pampa. Data: MAAP.

The Base Map shows the location of illegal gold mining along the Pariamanu River, in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region).

For context, La Pampa (the previous epicenter of illegal mining) and the regional capitol city of Puerto Maldonado are inlcuded. We also show another new illegal mining hotspot next to La Pampa, known as Apaylon.

In total, we have documented the deforestation of 204 hectares (504 acres) of primary forest caused by illegal gold mining in Pariamanu since 2017, indicated in red.

Note that this deforestation is located within Brazil nut forestry concessions and outside the “mining corridor,” thus clearly indicating its illegality.

Satellite Video: Illegal Gold Mining Deforestation in Pariamanu

We present a satellite image video showing an example of illegal gold mining in the Pariamanu area. These images show the deforestation of 71 hectares (175 acres) between 2016 (first image) and 2021 (last image), in the area indicated by the white inset box in the Base Map above. Note that each image is from July of each year (2016-20), with the exception of 2021 which shows January and March.

Satellite image video. Data: Planet.

Planet link: https://www.planet.com/stories/illegal-gold-mining-in-southern-peruvian-amazon-pa-6DfO4KuGg

MAAP Reports & Government Action

Operativo en Pariamanu, septiembre del 2020. Foto: FEMA Madre de Dios.

The first MAAP report about Pariamanu was published in November 2016, where we described “the start of mining in a new area” (MAAP #50). We found the mining-caused deforestation of 69 hectares (170 acres) on the banks of the Pariamanu river.

In January 2020, we published the second MAAP report about Pariamanu, documenting that the mining deforestation increased to 99 hectares (245 acres) (MAAP # 115). In this report, we warned that there were indications that some miners displaced by Operation Mercury (in February 2019) have moved to this area.

In response to this situation, the Peruvian Government, led by the Special Prosecutor for Environmental Matters (known as FEMA), carried out a series of field operations in 2020 (May, August and September, respectively), as an extension of Operation Mercury focused on cracking down on the illegal mining in Pariamanu.

The operations were effective in destroying mining equipment and sending a strong message that the government was engaged in this area.

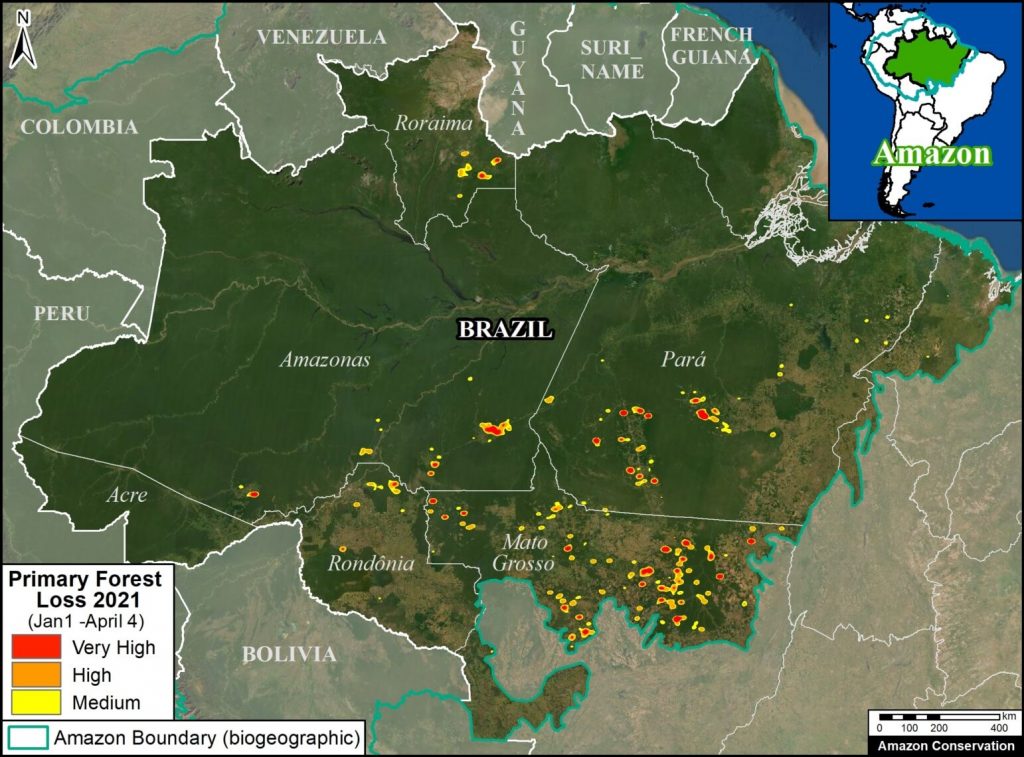

However, we found that gold mining deforestation continued in several small areas between October 2020 and March 2021 (see Image 2), reaching the new total of 204 hectares (504 acres).

Fortunately, the government continues to respond effectively. Most recently (March 19, 2021), FEMA and the Peruvian Coast Guard carried out a new operation in Pariamanu, finding an illegal mining camp and equipment.

As mentioned above, the objective of this section (and this report) is to present Pariamanu as an emblematic case that links technology with the rapid response action of public entities to address illegal activity in the Amazon. It also represents a concrete case of strategic collaboration between civil society and the government to try and achieve zero illegal deforestation (and avoided deforestation).

Image 2. Data: Planet, MAAP.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Novoa (ACCA), G. Palacios (ACA), and A. Felix, K. Nielsen, A. Caceres, I. Canelo, J. Carlos Guerra, O. Liao, y H. Che Piu from USAID’s PREVENT Project, for their helpful comments on this report.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that is working with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This publication is made possible with the support of the American people through USAID. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

This work was also supported by NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation), ICFC (International Conservation Fund of Canada), and EROL Foundation.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2021) New Illegal Gold Mining Hotspot in Peruvian Amazon – Pariamanu. MAAP: 137.

Download PDF of this article

Ruthmery Pillco, who leads field activities for the Community-Based Reforestation to Protect Andean bears project, was recently announced as one of fifteen changemakers worldwide to be selected for National Geographic’s Emerging Explorers award. She joins a global community of National Geographic Explorers that include a diverse array of scientists, educators, storytellers, and conservationists.

Ruthmery Pillco, who leads field activities for the Community-Based Reforestation to Protect Andean bears project, was recently announced as one of fifteen changemakers worldwide to be selected for National Geographic’s Emerging Explorers award. She joins a global community of National Geographic Explorers that include a diverse array of scientists, educators, storytellers, and conservationists.  National Geographic’s Emerging Explorers are selected annually from a global pool of candidates, and come from a variety of fields ranging from anthropology and earth sciences to technology and filmmaking. Aside from Ruthmery’s species conservation work, the projects from this year’s Emerging Explorers’ include ocean exploration, inventing space technologies, and understanding the past through archaeology and anthropology, among others.

National Geographic’s Emerging Explorers are selected annually from a global pool of candidates, and come from a variety of fields ranging from anthropology and earth sciences to technology and filmmaking. Aside from Ruthmery’s species conservation work, the projects from this year’s Emerging Explorers’ include ocean exploration, inventing space technologies, and understanding the past through archaeology and anthropology, among others.

Our real-time satellite monitoring efforts recently discovered that

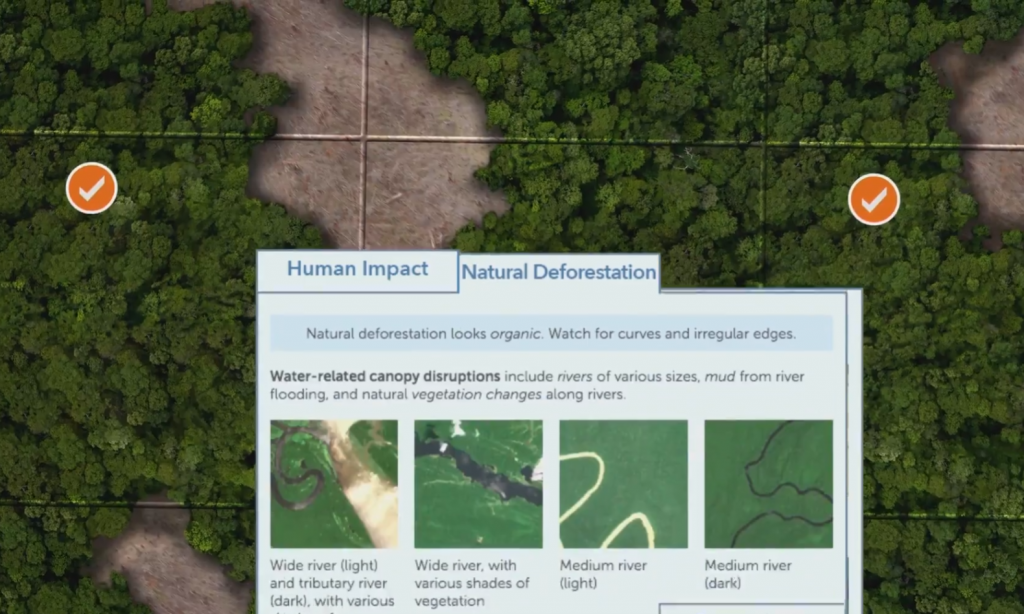

Our real-time satellite monitoring efforts recently discovered that  social innovation project, the company has been using crowd-driven artificial intelligence to help track, and ultimately stop, deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest since last year. So far over 845,000 square kilometers (around 280 million acres) of the rainforest have been analyzed by the general public to date, providing essential data for machine learning.

social innovation project, the company has been using crowd-driven artificial intelligence to help track, and ultimately stop, deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest since last year. So far over 845,000 square kilometers (around 280 million acres) of the rainforest have been analyzed by the general public to date, providing essential data for machine learning.

Loading...

Loading...