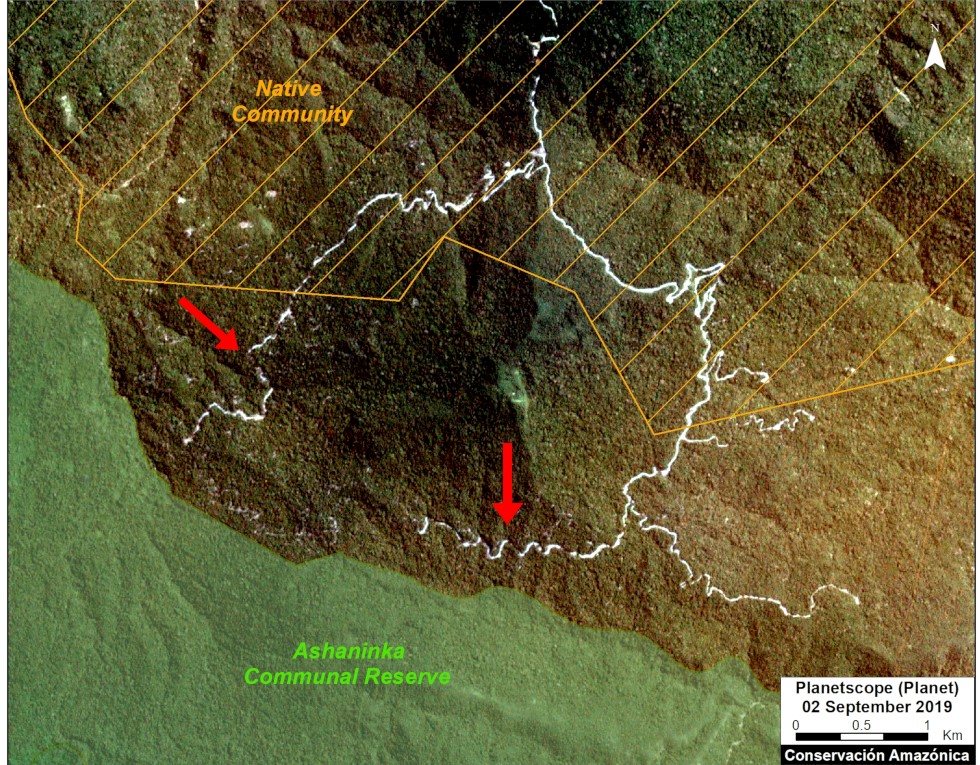

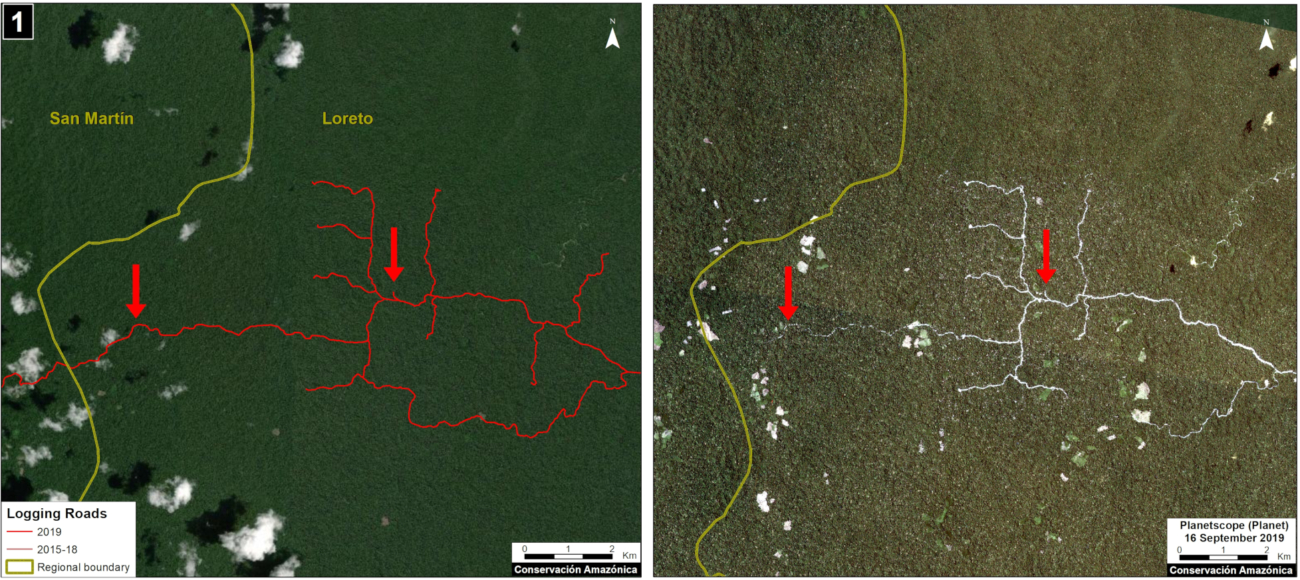

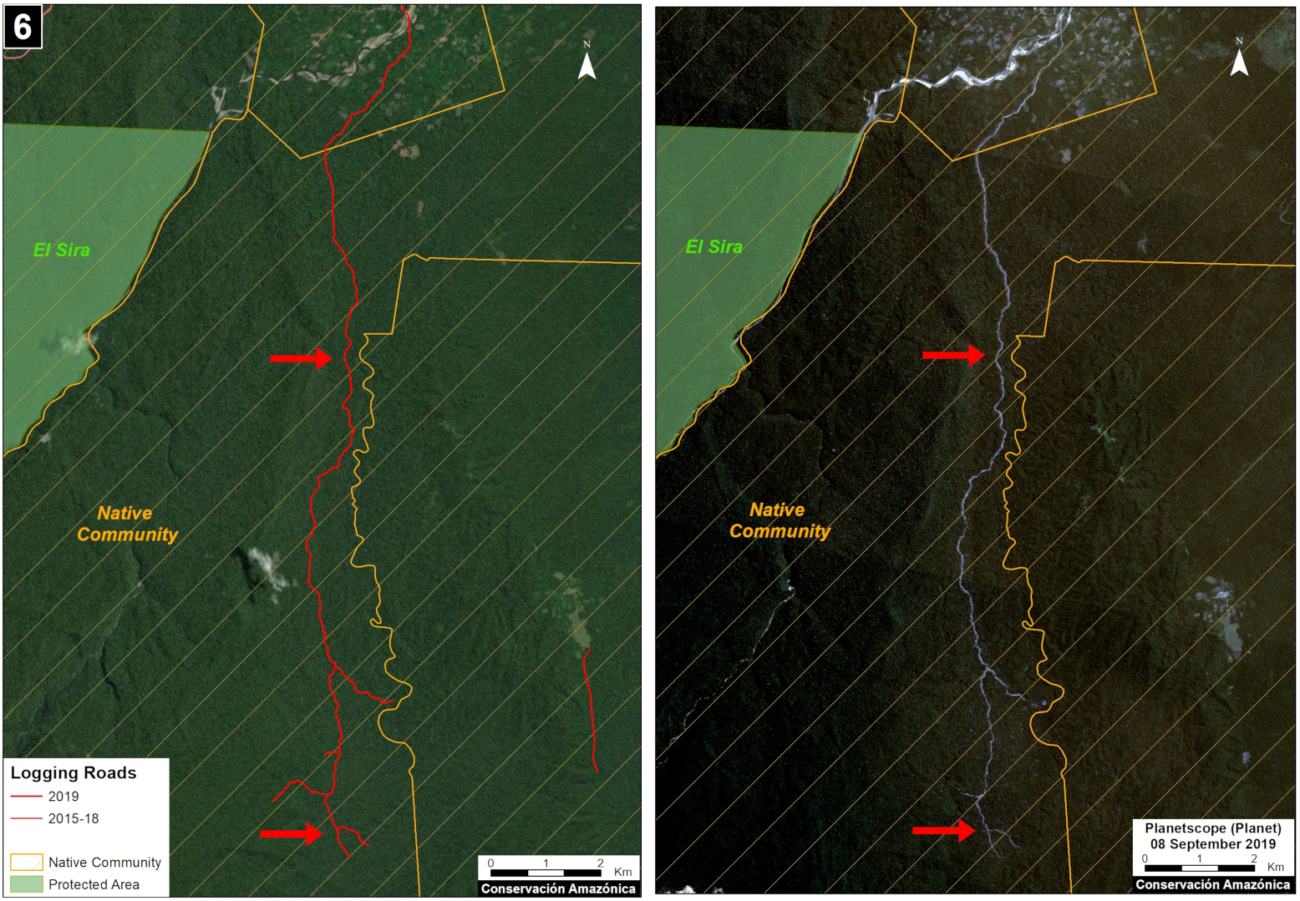

Image 1. Example of a 2019 logging road with signs of illegality. Data: Planet.

In the Peruvian Amazon, the widespread illegal logging is difficult to detect with satellites because it is selective for high-value species (not clearcutting).

It is possible, however, to detect the associated logging roads.

In this report, we present a novel technique to identify illegal logging: analyze new logging roads in relation to detailed land use data available from government agencies.

Thus, our new method detects the crime in real-time and preventive action is still possible. This is important because when an intervention against illegal logging normally occurs, stopping a boat or truck with illegal timber, the damage is done.

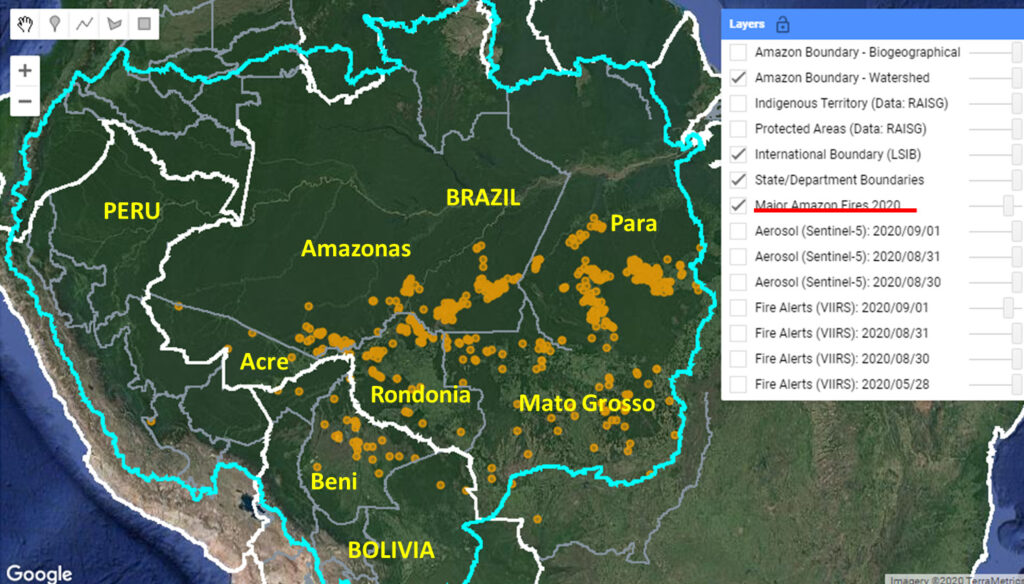

This analysis has two parts. First, we identified the new logging roads built in the Peruvian Amazon during 2019, updating our previous work for 2015-18 (see Base Map).

Second, we analyzed the new logging road data in relation to governmental land use information in order to identify possible illegality.

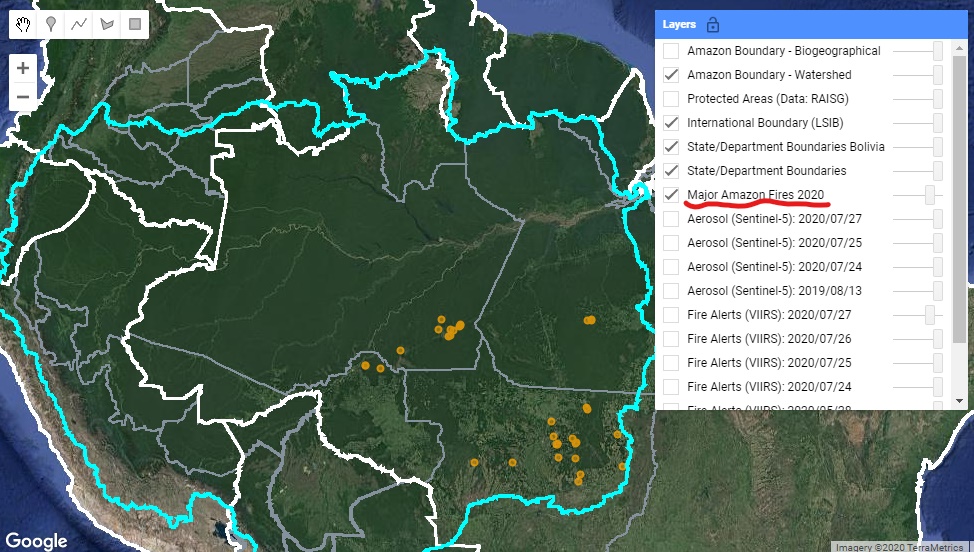

This data is from 2019, but we are now applying this technique in real time during 2020.

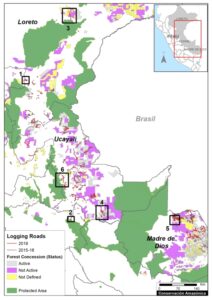

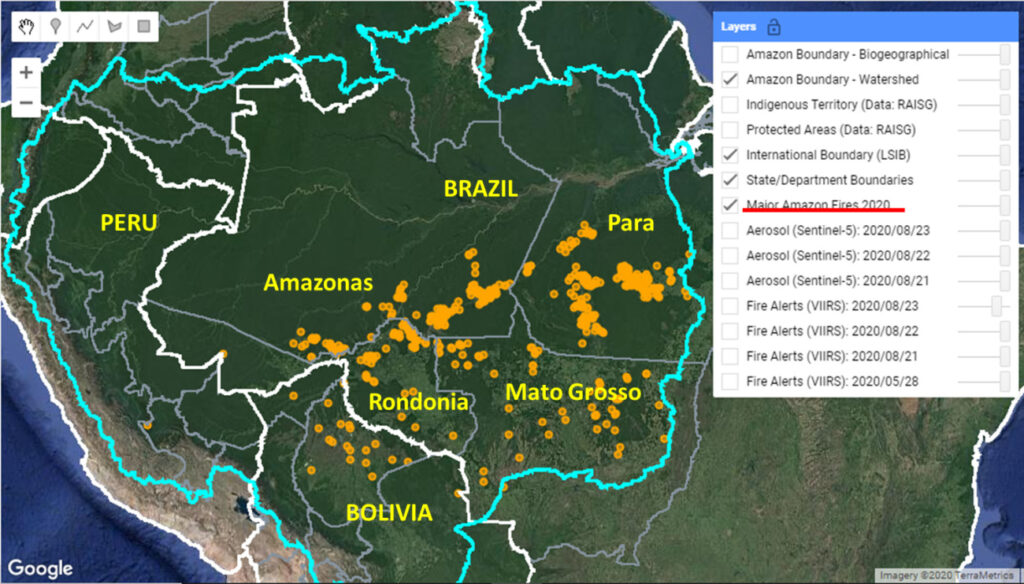

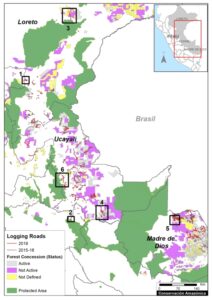

Base Map. 2019 Logging roads, in relation to 2015-18 logging roads. Data: MAAP.

Logging Roads 2019

The Base Map illustrates the location of logging roads built in the Peruvian Amazon during the last 5 years.

Previously (MAAP #99), we documented the construction of 3,300 kilometers of logging roads between 2015 and 2018.

Here, we estimate the construction of an additional 1,500 kilometers in 2019 (see red).

Note that forest roads are mainly concentrated in the Ucayali, Madre de Dios and Loreto regions.

Below, we show three types of possible illegality that detected in 2019:

- Logging roads in areas without forestry concessions or permits (Cases 1-2).

.

- Logging roads in existing forest concessions, but whose current status is defined as “Non-Active or Undefined” (Cases 3-5).

.

- Logging roads in Native Communities (Case 6).

Cases of Possible Illegality

Logging roads in areas without forestry concessions or permits

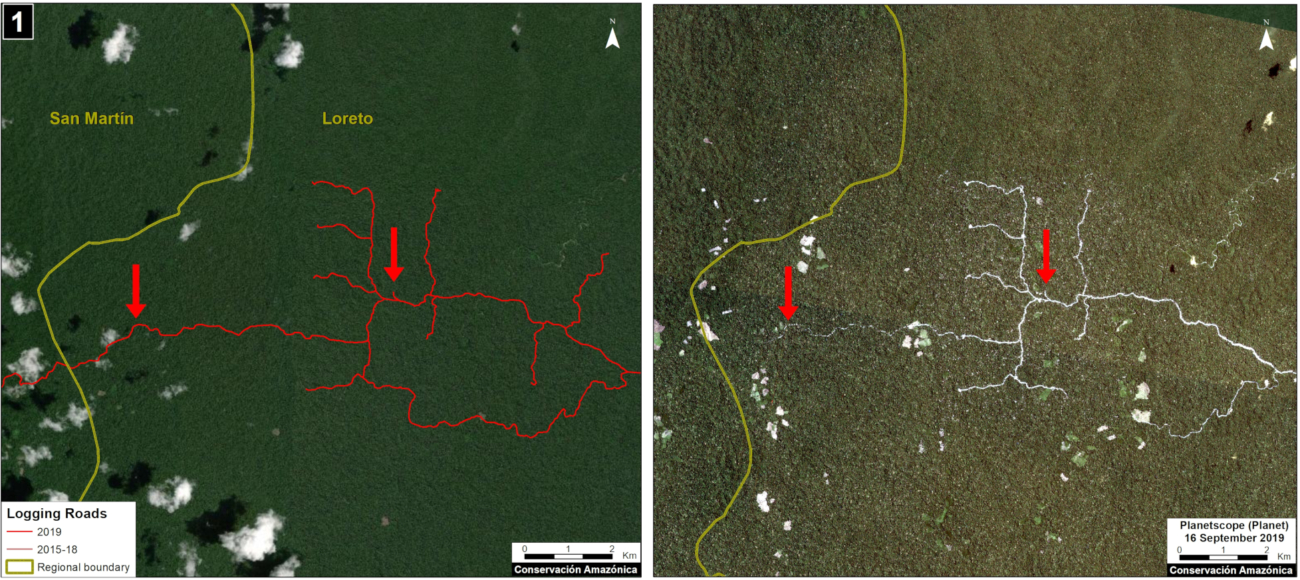

Case 1. We detected the opening of a new logging road network (55 km) in an area without forestry concessions or permits, between the limits of the Loreto and San Martín regions. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 1. Data: MAAP, Planet. Click to enlarge.

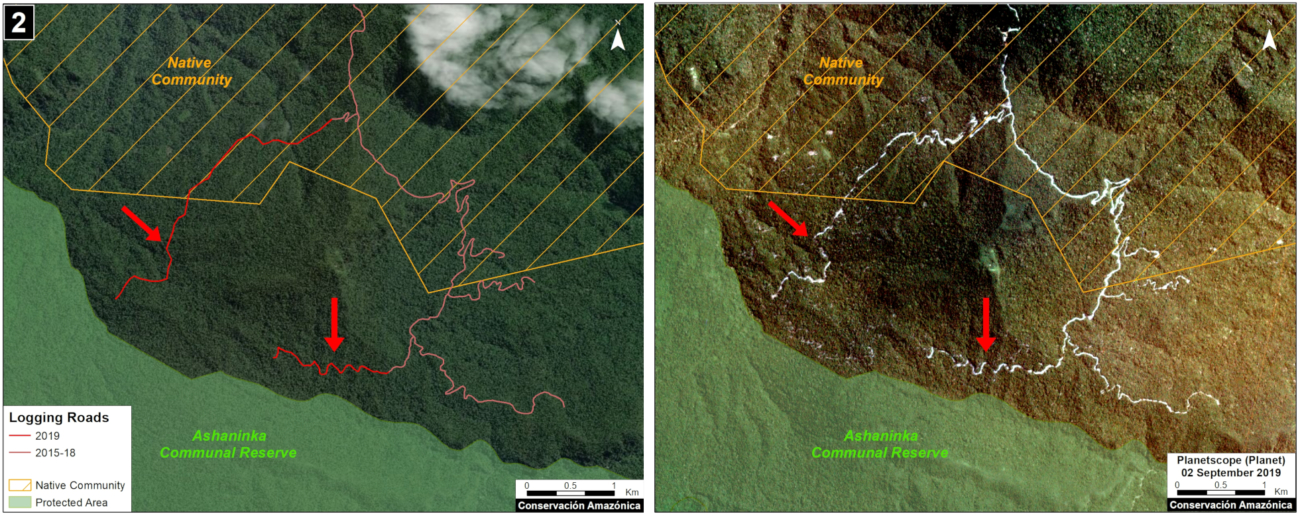

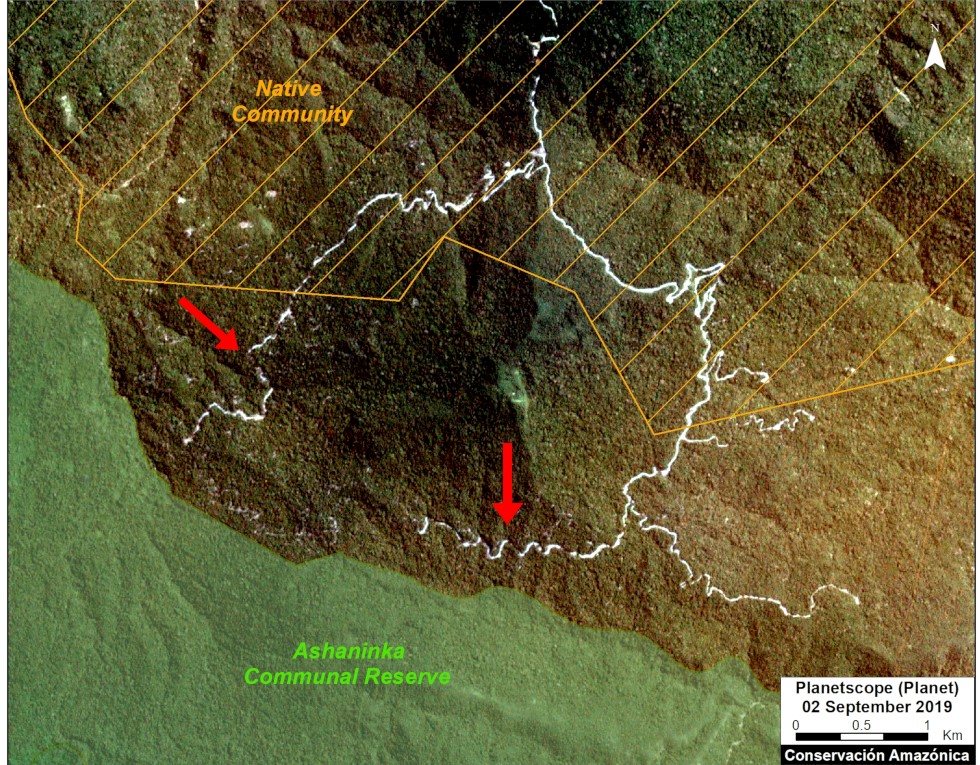

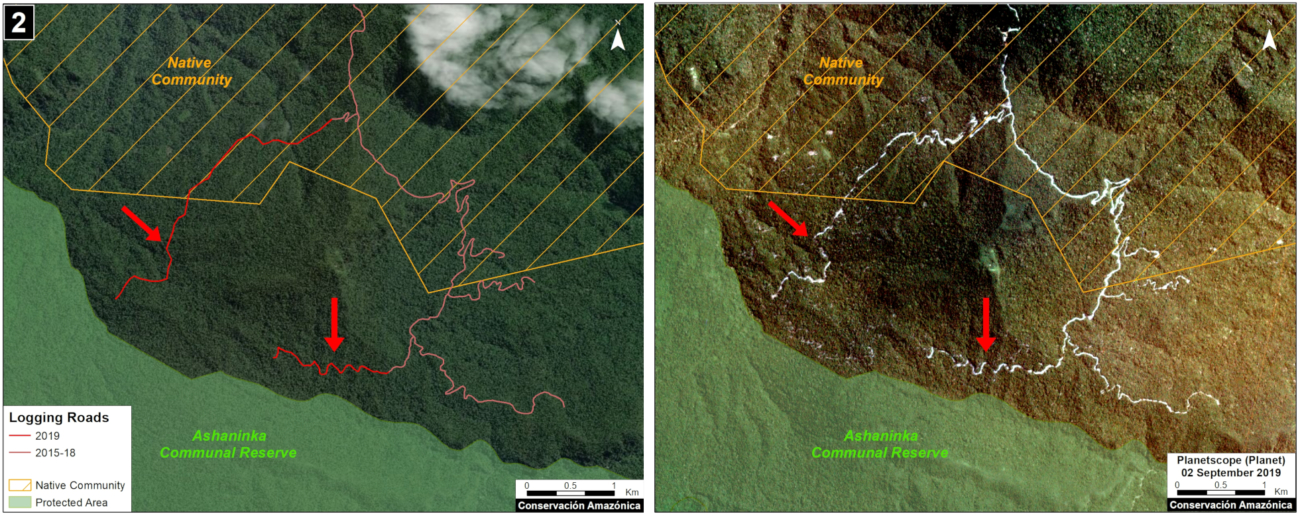

Case 2. We detected the construction of a new logging road network (5.8 km) in the buffer zone of Asháninka Communal Reserve, reaching only 300 meters from the protected area. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 2. Data: MAAP, Planet, IBC, SERNANP. Click to enlarge.

Logging roads in existing forest concessions, but whose current state is labelled as “Non-Active or Undefined”

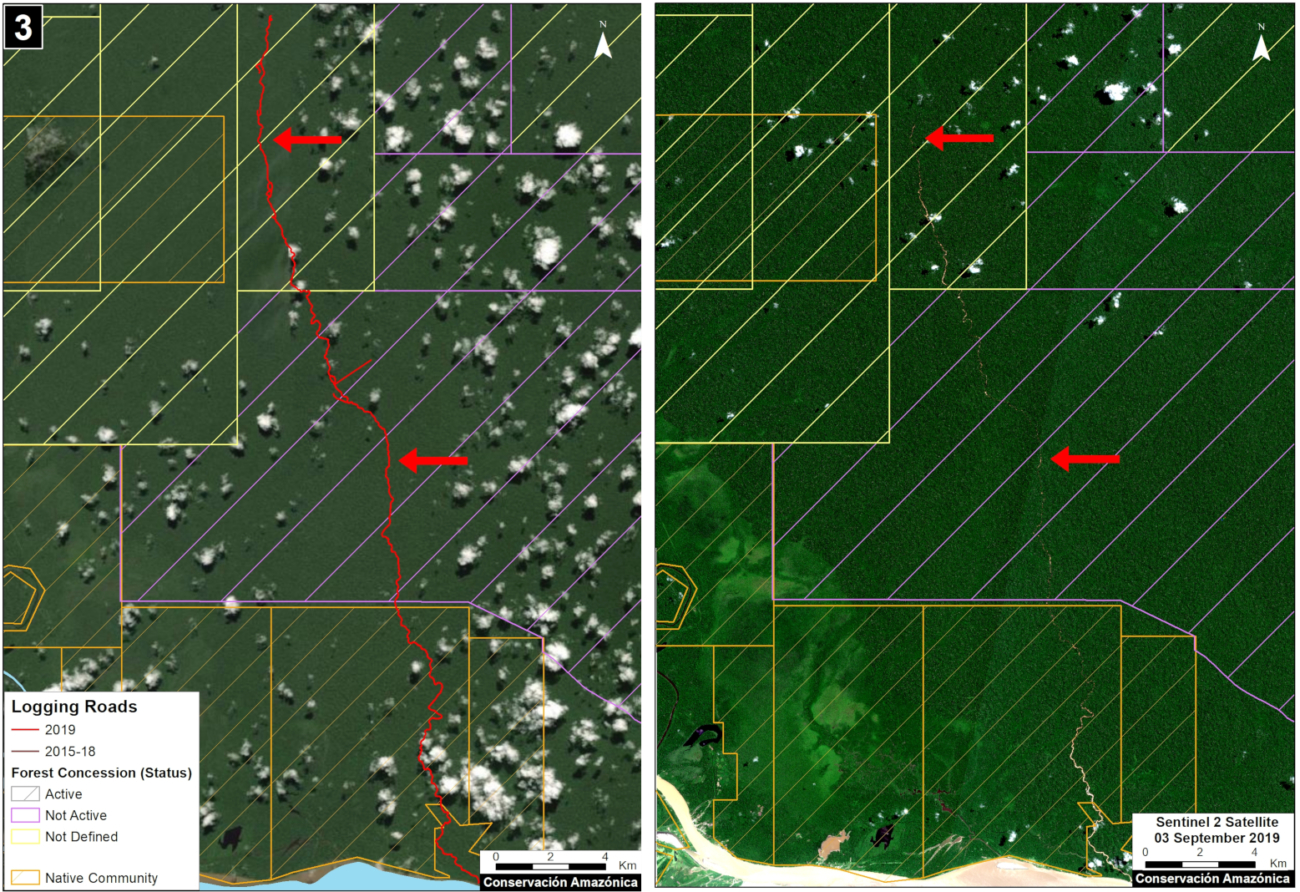

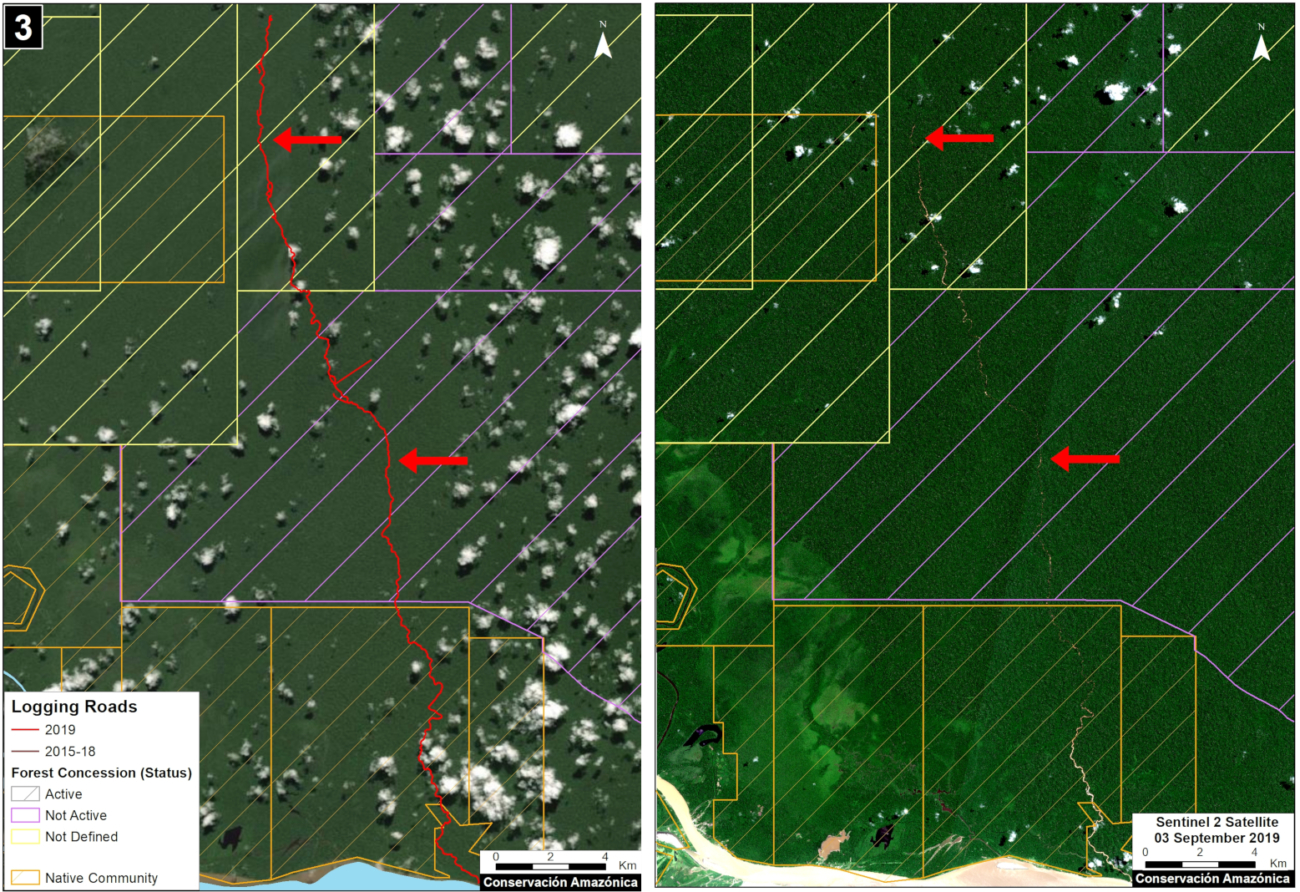

Case 3. We detected the construction of a new logging road (45.3 km) that crosses a native community and reaches a forest concession whose status is defined as “Undefined,” in the Loreto region just north of Pacaya Samiria National Reserve. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 3. Data: MAAP, ESA, IBC, SERFOR. Click to enlarge.

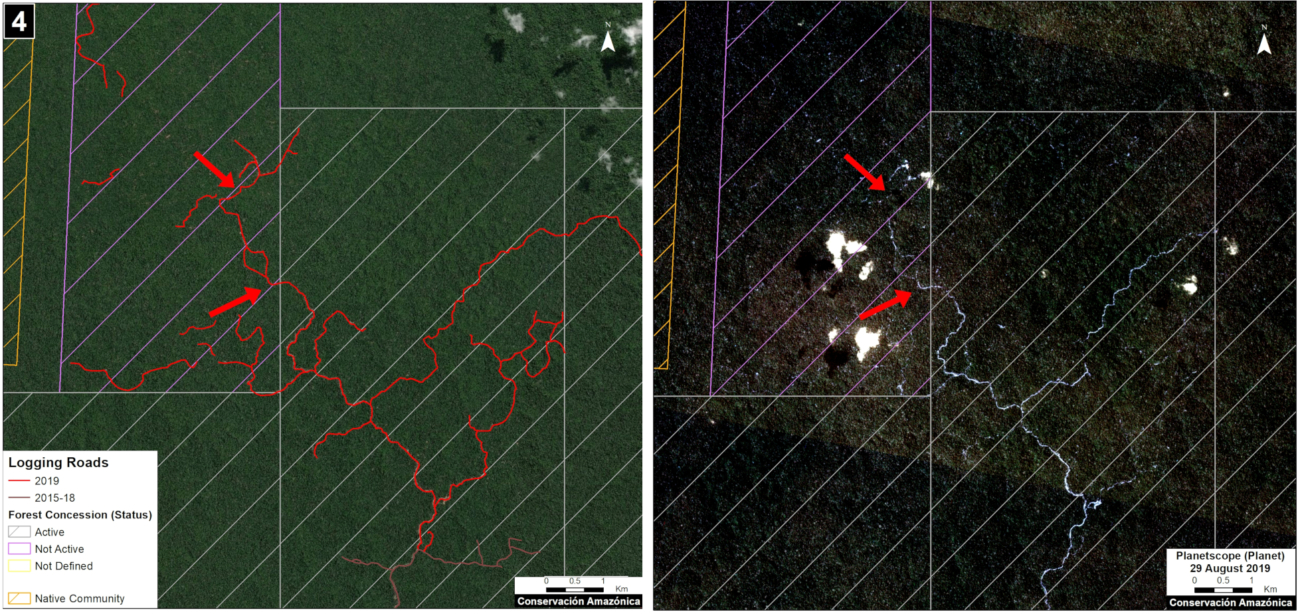

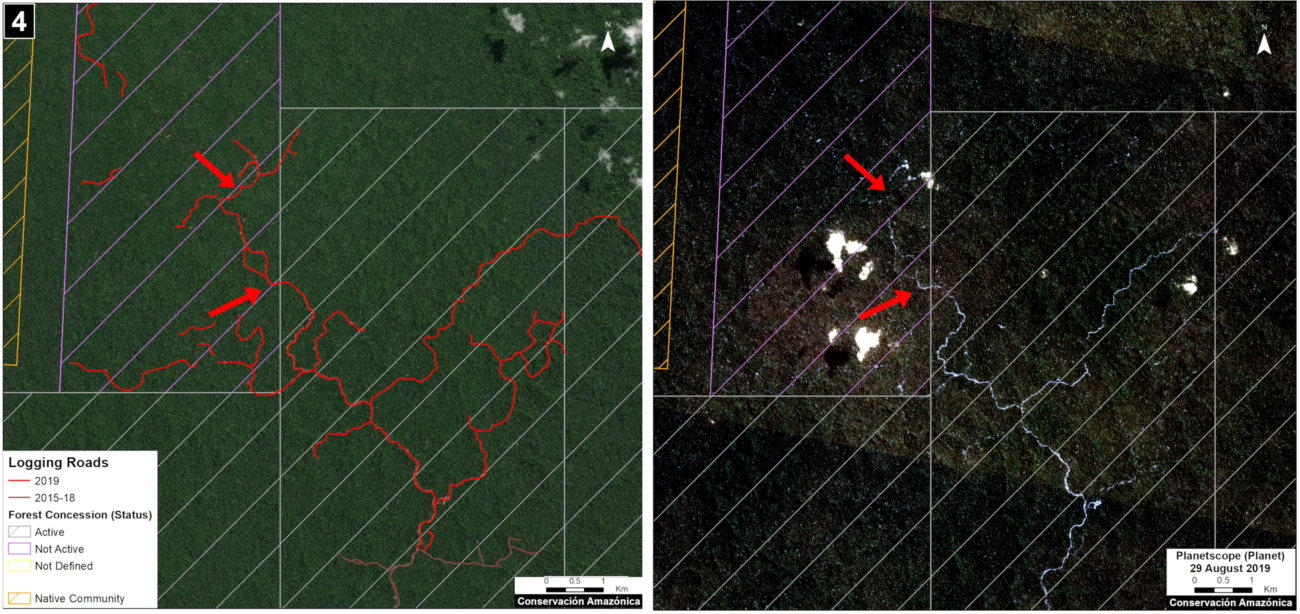

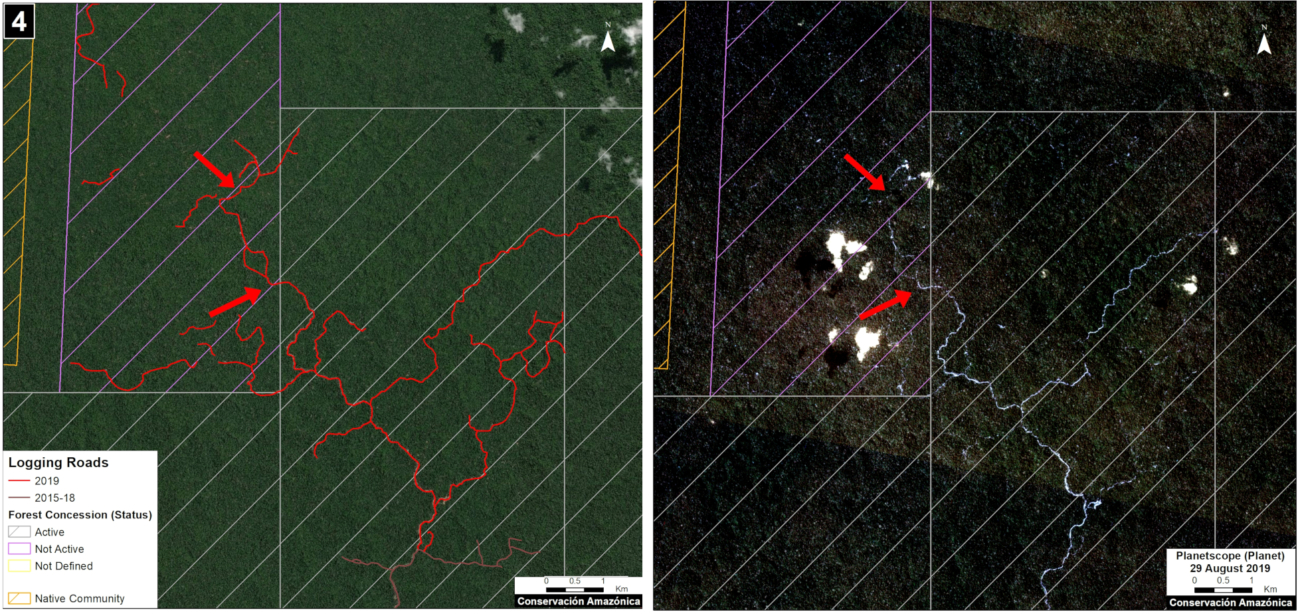

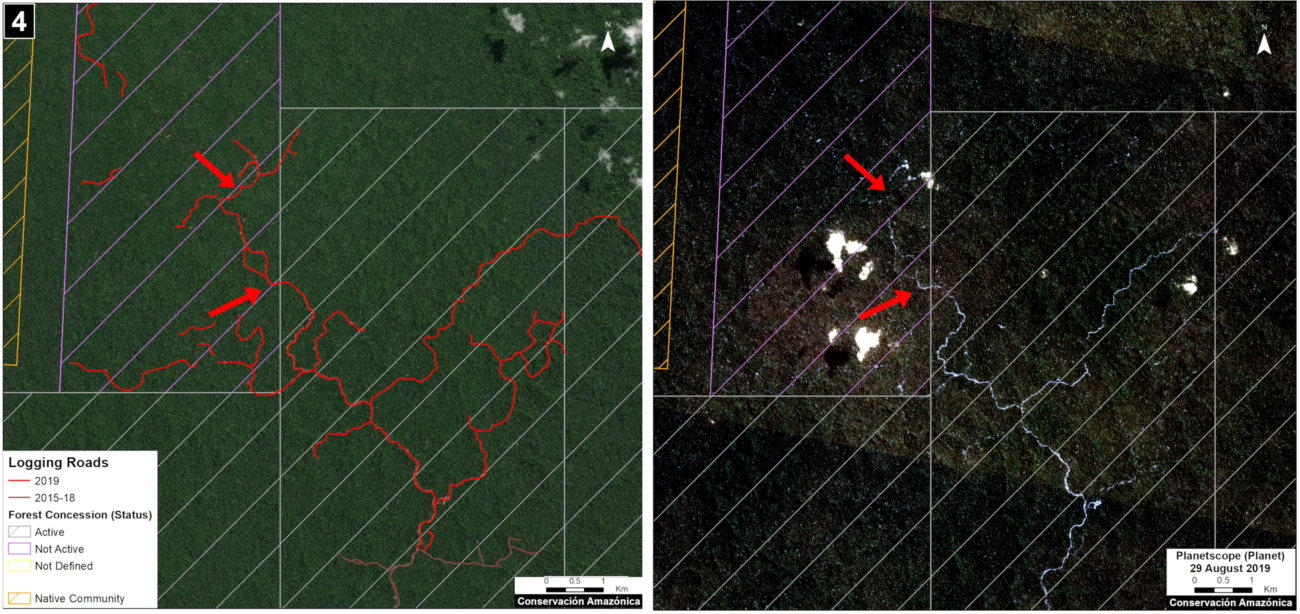

Case 4. We detected the construction of a new logging road network (53.2 km), of which nearly half (21.4 km) crosses a forest concession whose status is defined is “Non Active”, near the town of Sepahua in the Ucayali region. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 4. Data: MAAP, Planet, IBC, SERFOR. Click to enlarge.

Case 5. We detected the construction of a new logging road (17.7 km) in a forestry concession whose current status is defined as “Non Active,” in the Madre de Dios region. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 5. Data: MAAP, ESA, IBC, SERFOR. Click to enlarge.

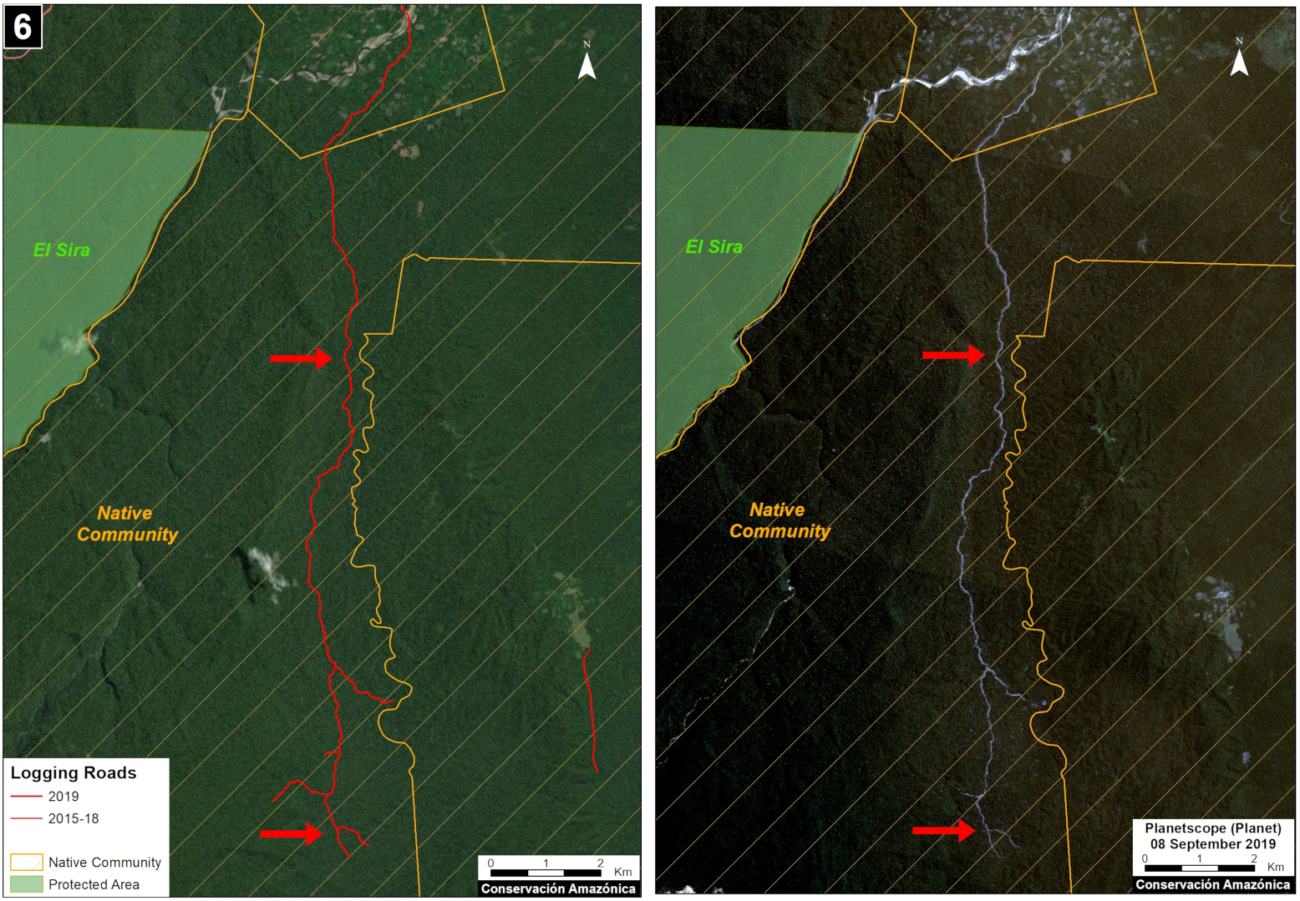

Logging roads in Native Communities

Case 6. We detected the construction of a logging road (23.4 km) within an indigenous community in the Ucayali region. We did not find evidence of a permit for this activity. The image shows the digitized logging roads (red, left panel), and non-digitized satellite image (right panel). The arrows provide reference points between panels.

Case 6. Data: MAAP, Planet, SERNANP, IBC, SERFOR. Click to enlarge.

Methodology

Our analysis included two main steps:

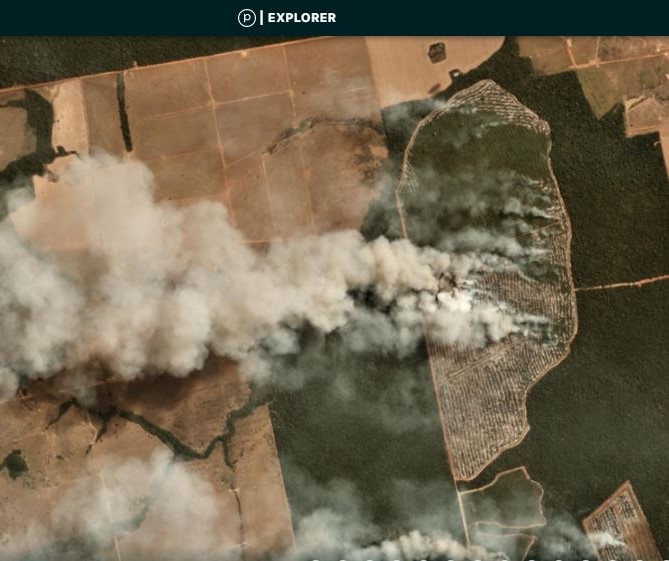

The first step consisted of evaluating linear patterns in the 2019 early warning and final forest loss data, available from Global Forest Watch (data from the University of Maryland) and Geobosques (data from the Peruvian Ministry of the Environment). From the linear patterns, we distinguished between logging access roads and other types of roads and highways. Logging roads tend to have linear patterns that branch into the interior of the forest where the commercial timber is found. Other types of roads have a more defined destination, such as towns or farms. Once logging roads were identified, we downloaded the associated high-resolution imagery (3 meters) from Planet Explorer and digitized the roads in ArcGIS. During this process, additional logging roads detected in the high resolution images were also digitized.

The second step focused on the legality analysis. The new logging road data were overlaid with other types of land use information, such as forestry concessions on the GeoSERFOR portal (SERFOR), permits and concessions on the SISFOR portal (OSINFOR), indigenous communities (IBC 2019), protected areas (SERNANP), population centers (INEI 2019), and official road networks (MTC 2018). For example, as shown above, this process identified logging roads near protected areas, within indigenous communities, and within non-active forest concessions.

We analyzed information on several websites now available from national and regional authorities, such as SISFOR (OSINFOR), GEOSERFOR (SERFOR), and IDERs (Spatial Data Infrastructure of Regional governments). These new resources provide valuable information, however may have limitations in ability to constantly update information on the status of concessions and forest permits, especially from regional governments.

References

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Valle (OSINFOR), A. Felix (DAI), D. Suarez (ACCA), and G. Palacios for their helpful comments on this report.

This report was conducted with technical assistance from USAID, via the Prevent project. Prevent is an initiative that, over the next 5 years, will work with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes in Loreto, Ucayali and Madre de Dios, in order to conserve the Peruvian Amazon.

This publication is made possible with the support of the American people through USAID. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US government.

Citation

Finer M, Paz L, Novoa S, Villa L (2020) Detecting Illegal Logging in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 123.

communities’ sustainable harvesting of herbs, fruits, and nuts. This forest alone contains nearly 10% of the world’s Brazil nut trees under production. It also connects nearby nature reserves, creating an important biodiversity corridor of protected lands in the region.

communities’ sustainable harvesting of herbs, fruits, and nuts. This forest alone contains nearly 10% of the world’s Brazil nut trees under production. It also connects nearby nature reserves, creating an important biodiversity corridor of protected lands in the region.

Our novel

Our novel

Sincerely,

Sincerely,

Amazon Conservation’s sister organization Conservación Amazónica – ACCA, with support from Google.org, just finished up a two-year initiative that trained community members to use cutting-edge satellite and field technologies to combat deforestation in the southern Peruvian Amazon, now protecting over 150,000 acres of lowland forests.

Amazon Conservation’s sister organization Conservación Amazónica – ACCA, with support from Google.org, just finished up a two-year initiative that trained community members to use cutting-edge satellite and field technologies to combat deforestation in the southern Peruvian Amazon, now protecting over 150,000 acres of lowland forests. Before this program, concessionaires and their communities lacked capacity to monitor these large, remote areas and a way to rapidly and safely report deforestation in their territories. Our innovative methodology of combining real-time satellite imagery analysis and drone field technology (which includes smartapps and other technologies developed by Google) with legal training, gave concessionaires the ability to detect and report deforestation as it happened in their territory. This is a stark contrast from before, when the only way to monitor thousands of acres of forests was through foot patrols that took days to complete.

Before this program, concessionaires and their communities lacked capacity to monitor these large, remote areas and a way to rapidly and safely report deforestation in their territories. Our innovative methodology of combining real-time satellite imagery analysis and drone field technology (which includes smartapps and other technologies developed by Google) with legal training, gave concessionaires the ability to detect and report deforestation as it happened in their territory. This is a stark contrast from before, when the only way to monitor thousands of acres of forests was through foot patrols that took days to complete.  Through this program, over 153,000 acres (62,000 hectares) of forests are now monitored and protected with technology by the local people we empowered. Moreover, technological kits were donated to each individual or local association, each containing a drone, a maintenance kit, a laptop and a printer, giving them the knowledge and tools needed to safeguard forests..

Through this program, over 153,000 acres (62,000 hectares) of forests are now monitored and protected with technology by the local people we empowered. Moreover, technological kits were donated to each individual or local association, each containing a drone, a maintenance kit, a laptop and a printer, giving them the knowledge and tools needed to safeguard forests.. The project, led by our director of our Southwest Amazon Drone Center, Carlos Castañeda, will continue to provide technical support to maintain the donated drones and training to reinforce what they learned, as well as be available to answer any questions that may arise during monitoring and surveillance of their concessions. Thus, the continuity of the project and its sustainability are ensured.

The project, led by our director of our Southwest Amazon Drone Center, Carlos Castañeda, will continue to provide technical support to maintain the donated drones and training to reinforce what they learned, as well as be available to answer any questions that may arise during monitoring and surveillance of their concessions. Thus, the continuity of the project and its sustainability are ensured.

Loading...

Loading...