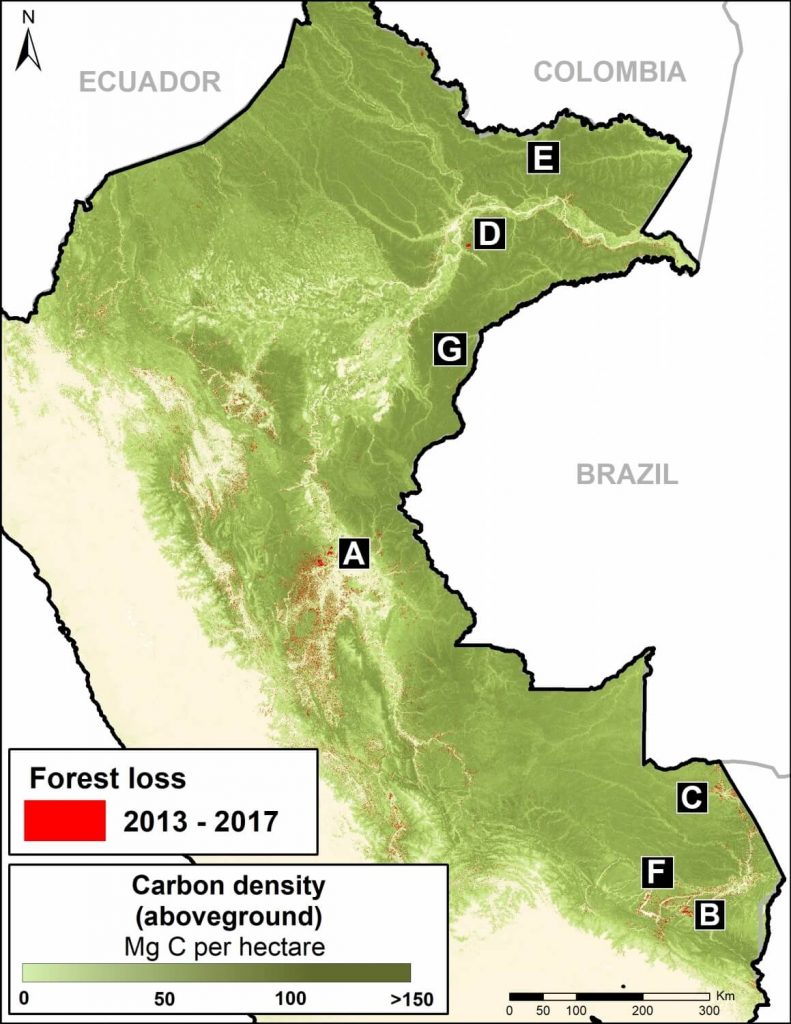

Base Map. Data: MINAM/PNCB, Asner et al 2014

Download PDF of this article

When tropical forests are cleared, the enormous amount of carbon stored in the trees is released to the atmosphere, making it a major source of global greenhouse gas emissions (CO2) that drive climate change.

In fact, a recent study revealed that deforestation and degradation are turning tropical forests into a new net carbon source for the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change.1

The Amazon is the world’s largest tropical forest, and Peru is a key piece of that. Researchers (led by Greg Asner at the Carnegie Institution for Science) recently published the first high-resolution estimate of aboveground carbon in the Peruvian Amazon, documenting 6.83 billion metric tons.2

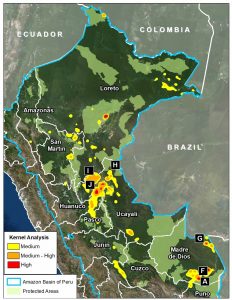

Here, we analyze this same dataset to estimate the total carbon emissions from deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon between 2013 and 2017. We estimate the loss of 59 million metric tons of carbon during these last five years, the equivalent of around 4% of annual United States fossil fuel emissions.3

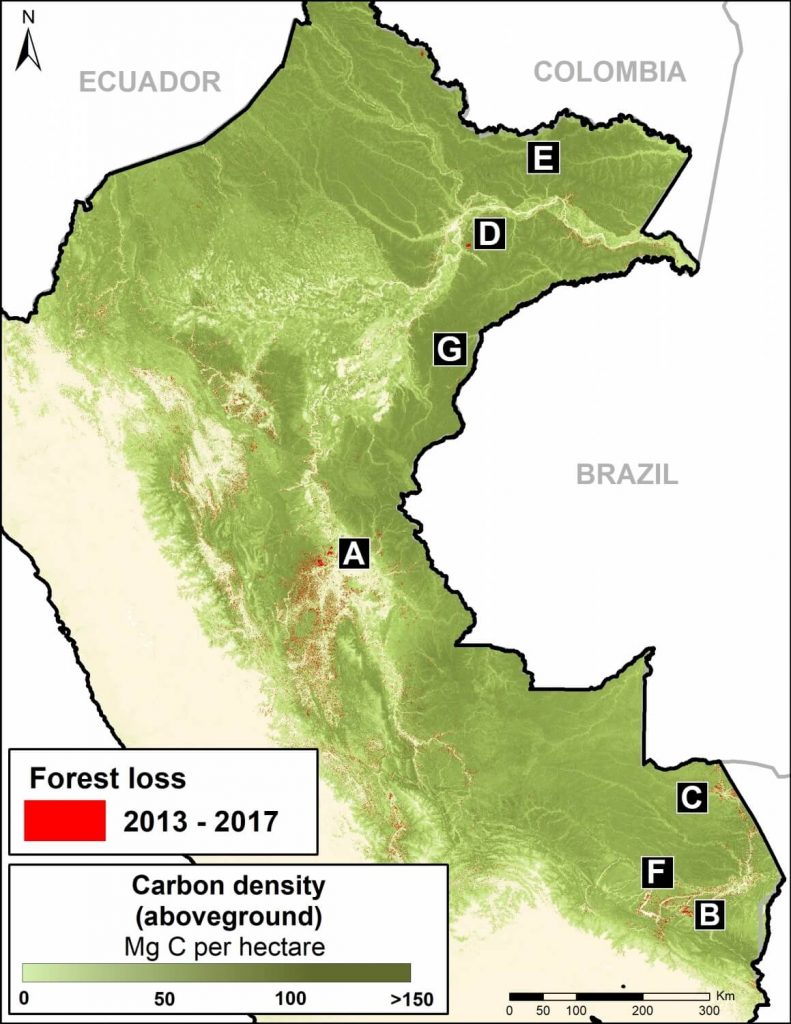

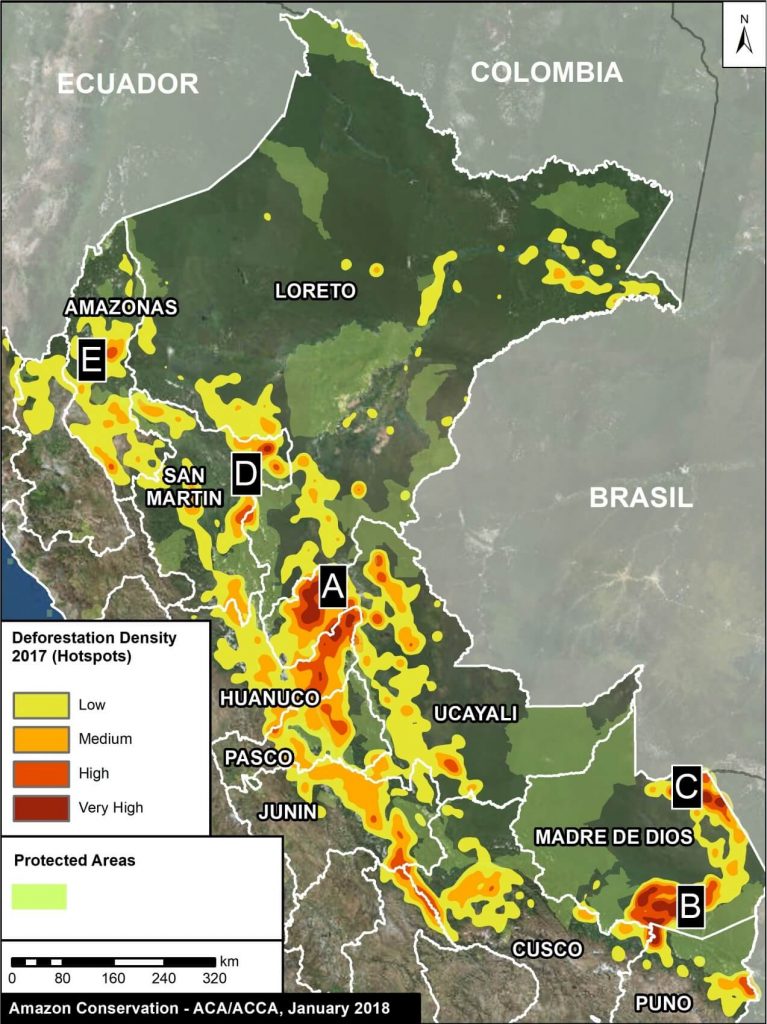

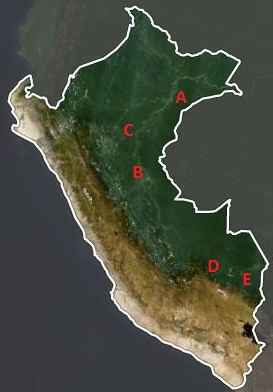

We present a series of zoom images to show how carbon loss happened in several key areas impacted by the major deforestation drivers: gold mining, large-scale oil palm and cacao plantations, and smaller-scale agriculture. The labels A-G correspond to the zooms below.

We also show how protected areas are protecting hundreds of millions of metric tons of carbon in some of the most important areas in the country.

On the positive side, having this detailed information may provide added incentives to slow deforestation and degradation as part of critical climate change strategies.

Major Findings

Data: Asner et al 2014

The base map (see above) shows, in shades of green, carbon densities across Peru. It also shows, in red, the forest loss layer from 2013 to 2017.

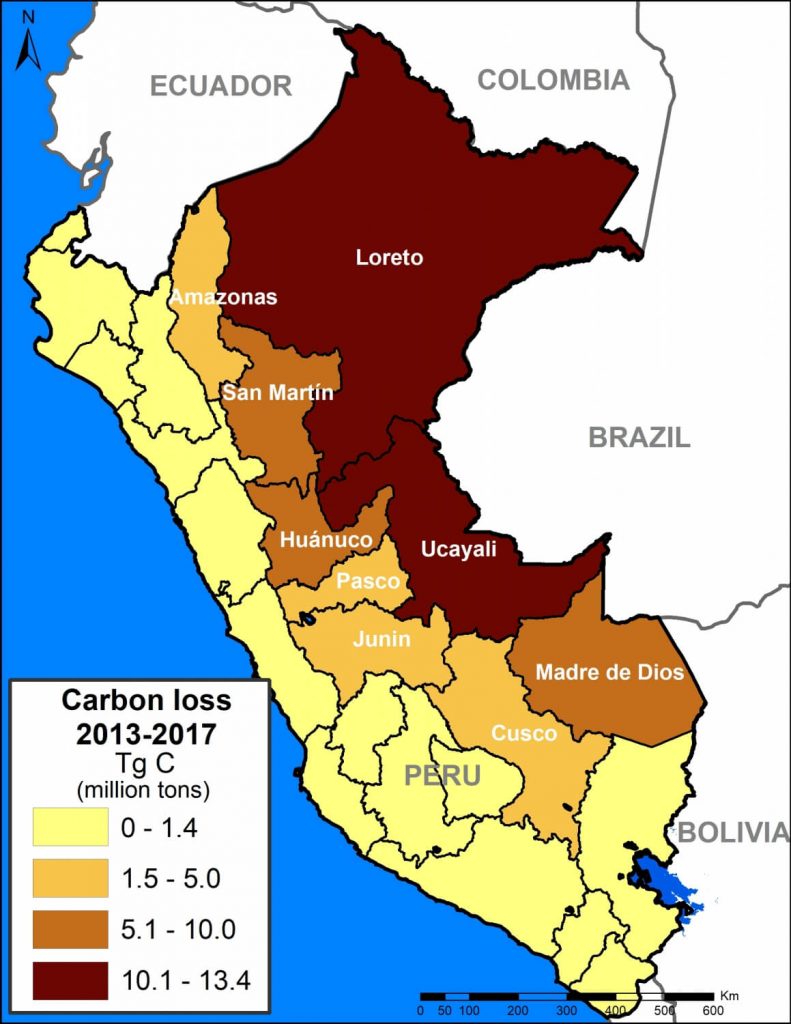

We calculated the estimated amount of carbon emissions from forest loss during these five years: 59.029 teragrams, or 59 million metric tons.

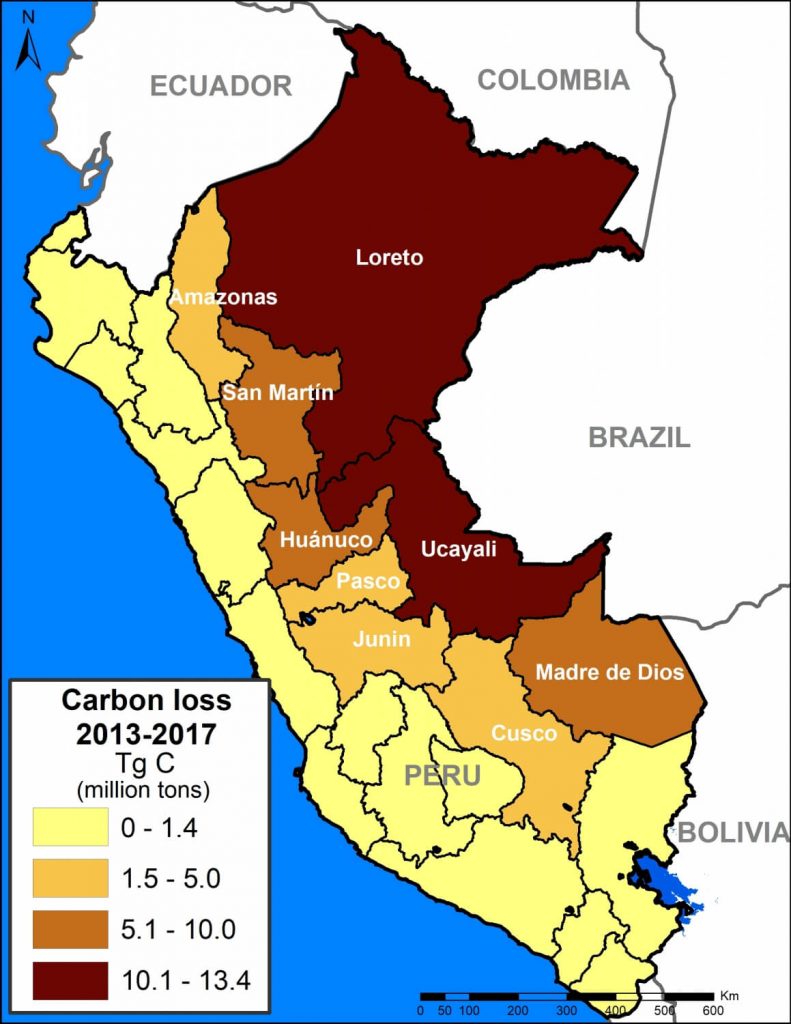

The regions with the most carbon loss are 1) Loreto (13.4 million metric tons), 2) Ucayali (13.2 million), 3) Huánuco (7.3 million), 4) Madre de Dios (7 million), and 5) San Martin (6.9 million).

These values include some natural forest loss. Overall, however, they should be considered underestimates because they do not include forest degradation (for example, selective logging).

A recent study revealed that degradation may account for 70% of emissions, thus total carbon emissions from forests in the Peruvian Amazon may be closer to 200 million metric tons.

Next, we show a series of zoom images to show how carbon loss happened in several key areas. We also show how protected areas and conservation concessions are protecting the most important carbon reserves.

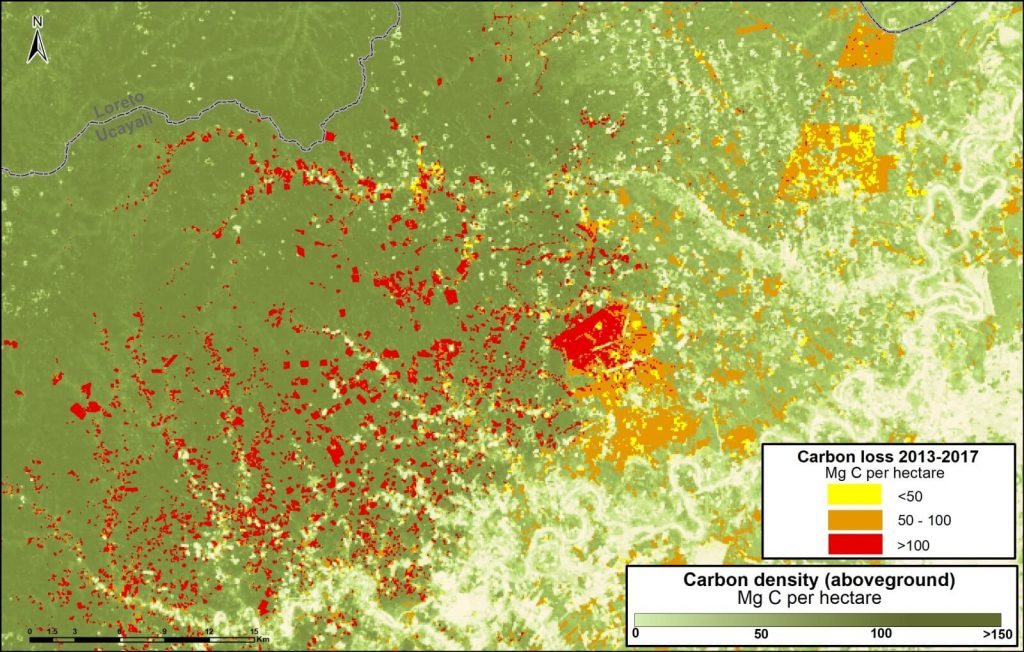

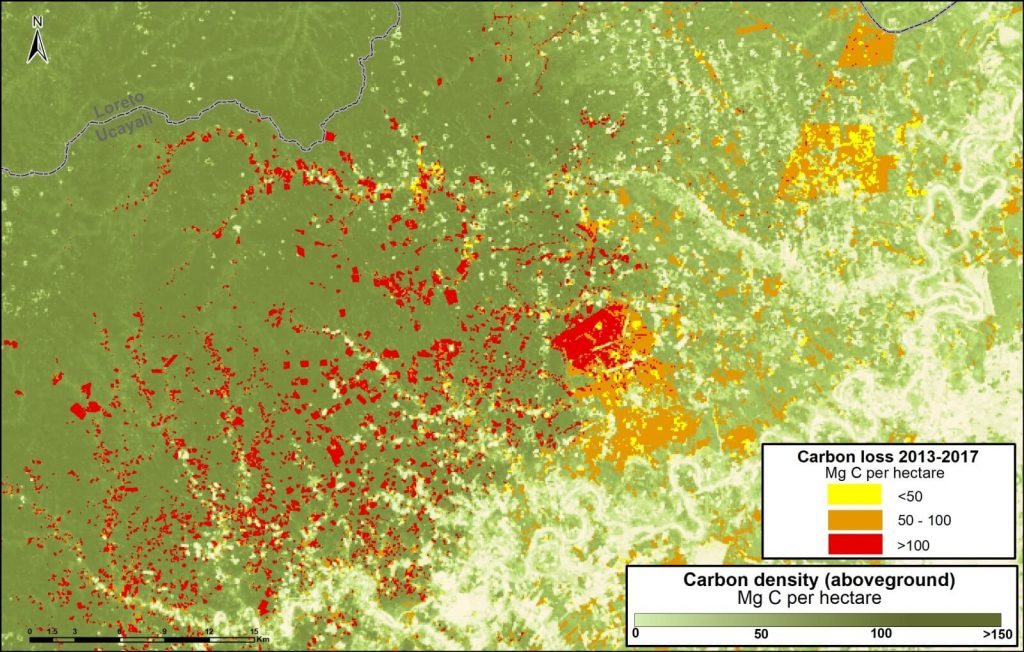

Zoom A: Central Peruvian Amazon

Image A shows the loss of 2.8 million metric tons of carbon in a section of the central Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali region). On the east side of image, note the loss due to two large-scale oil palm plantations (649,000 metric tons); on the west side, note small-scale agriculture penetrating deeper into high carbon density forest.

Image A. Central Peruvian Amazon. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

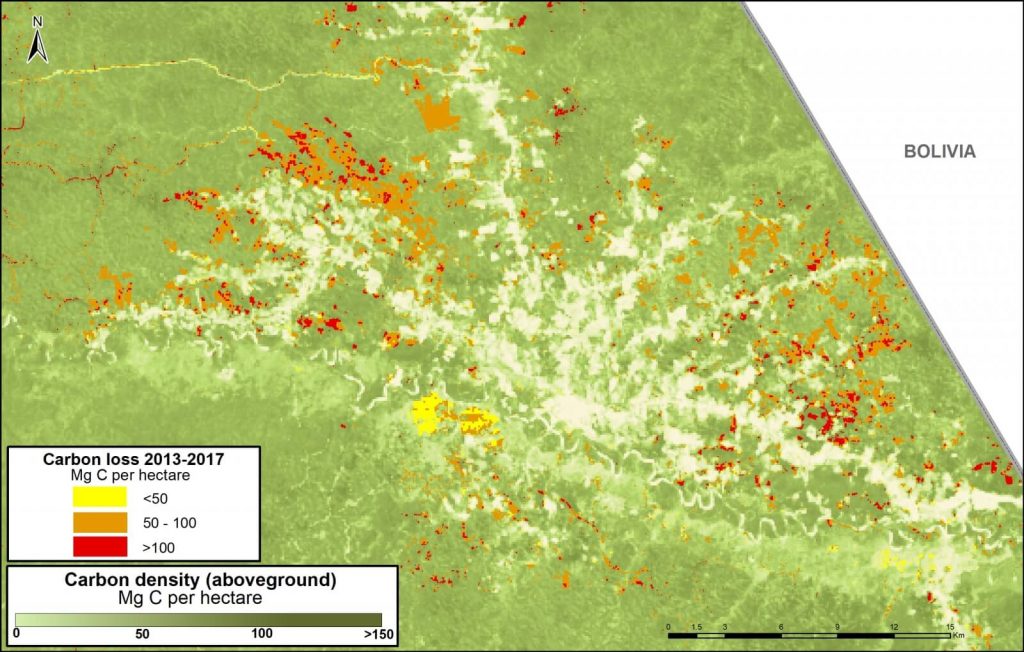

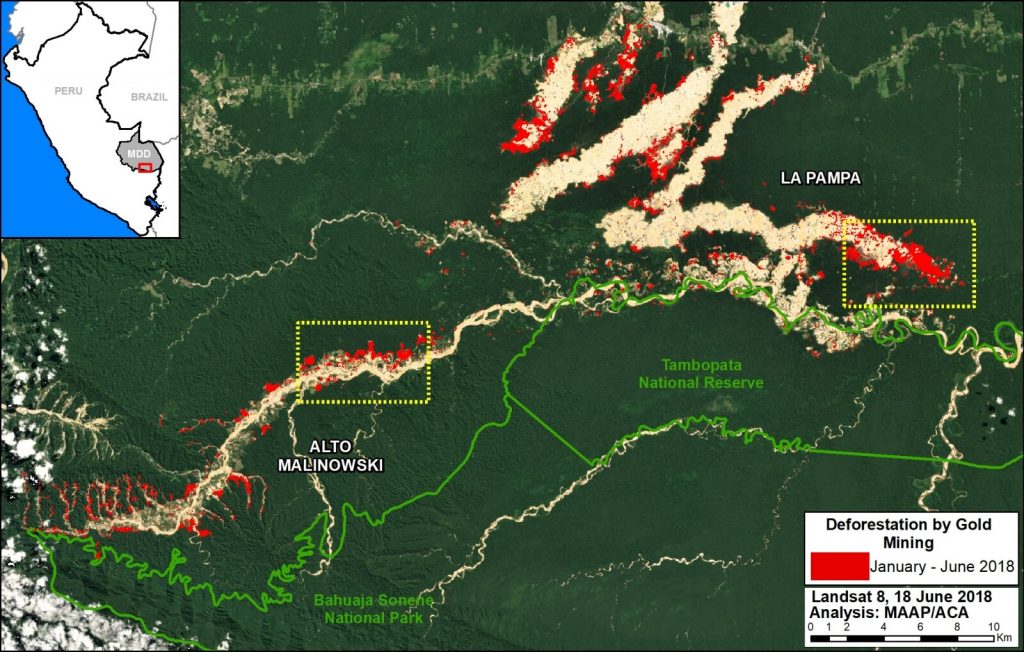

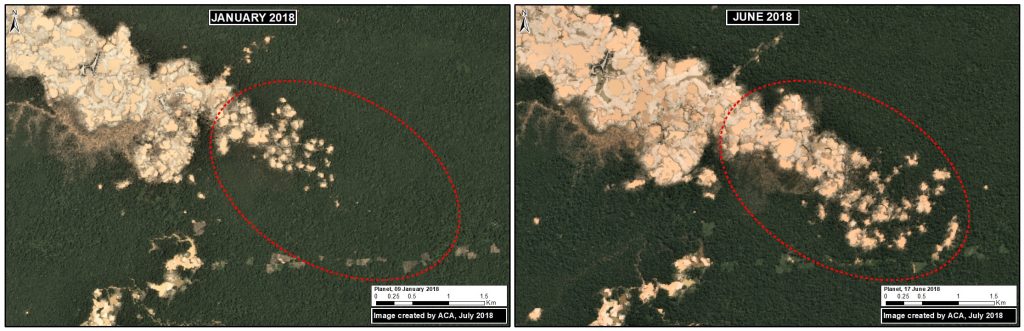

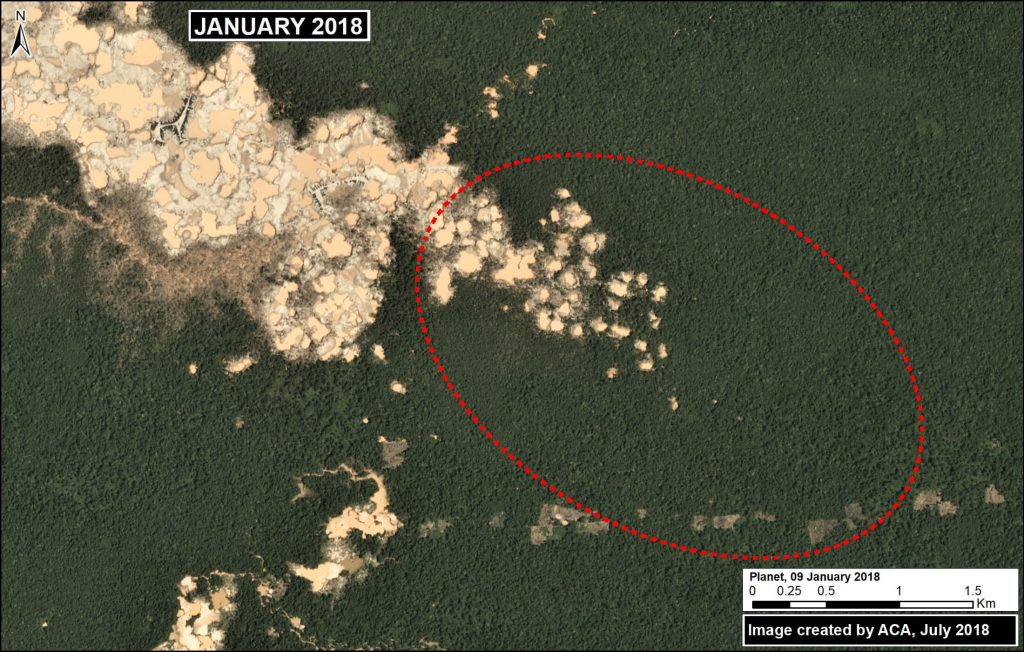

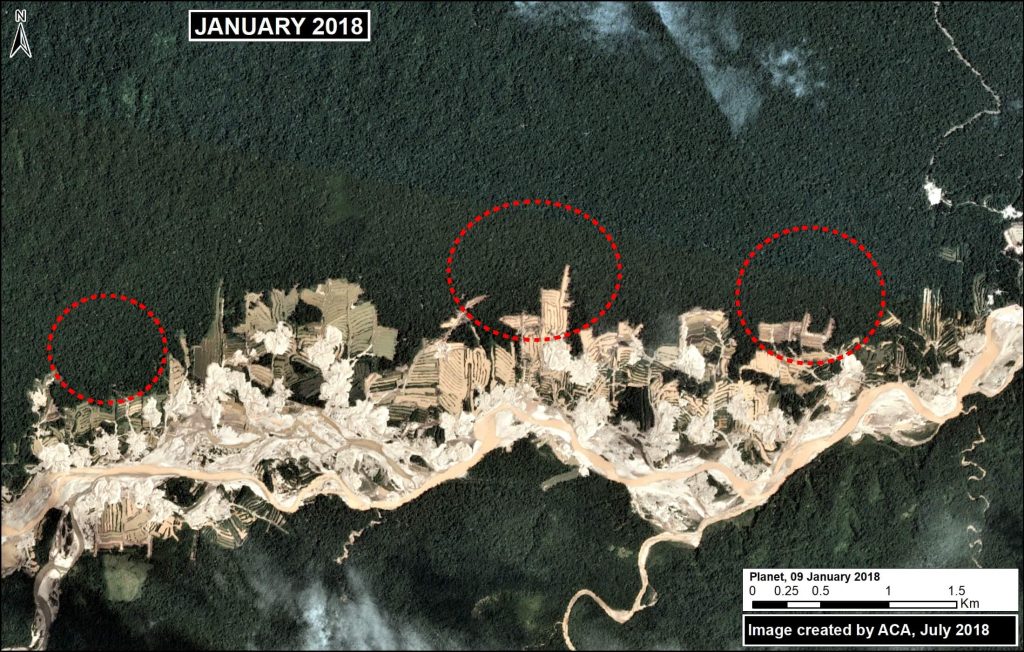

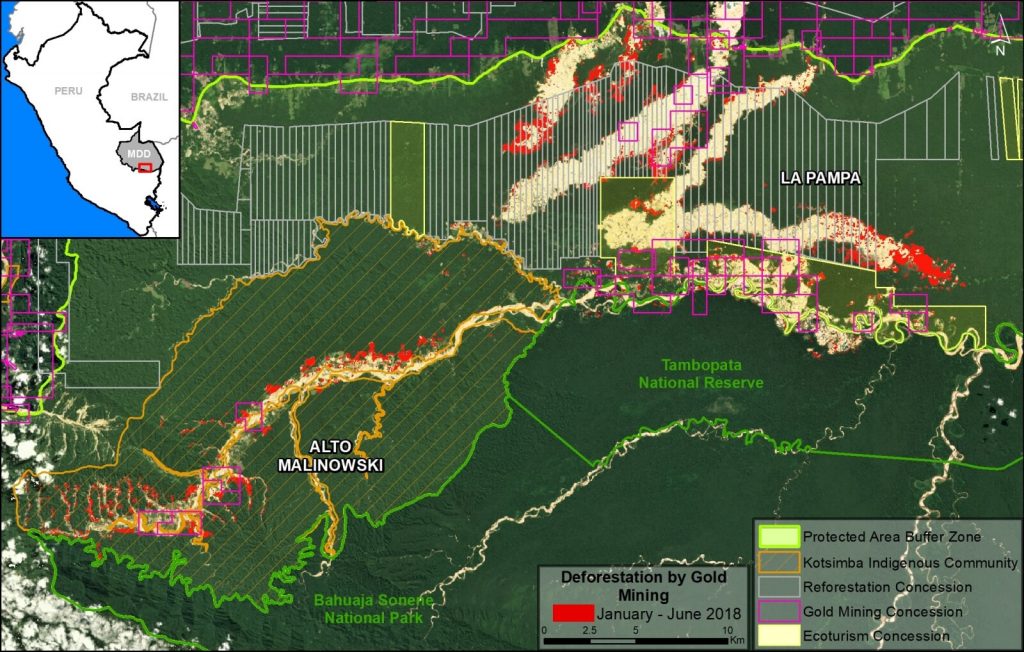

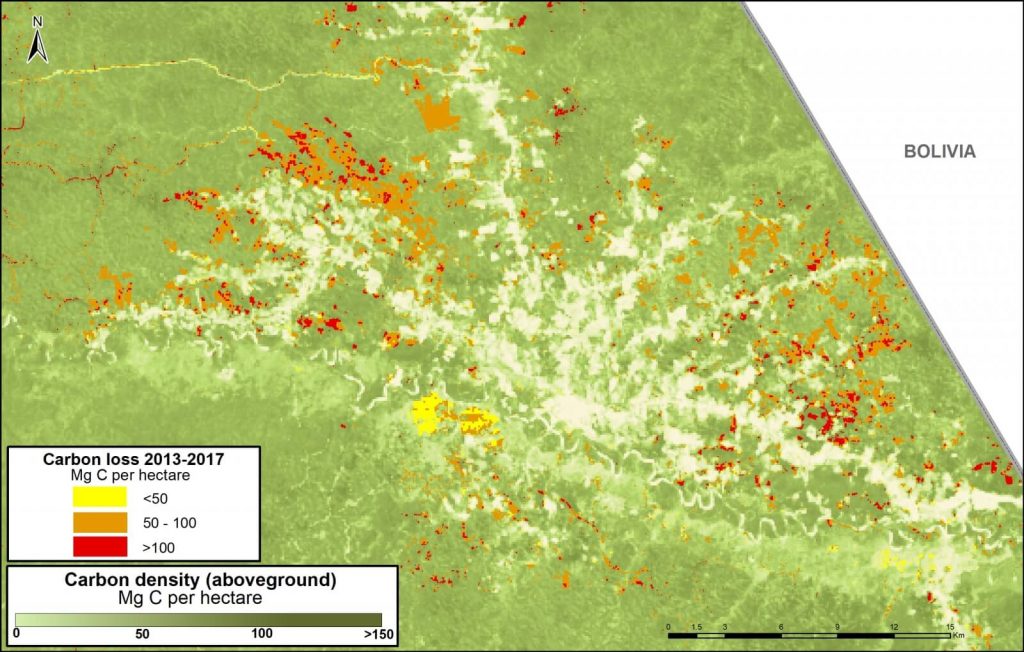

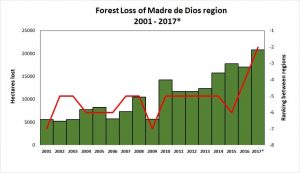

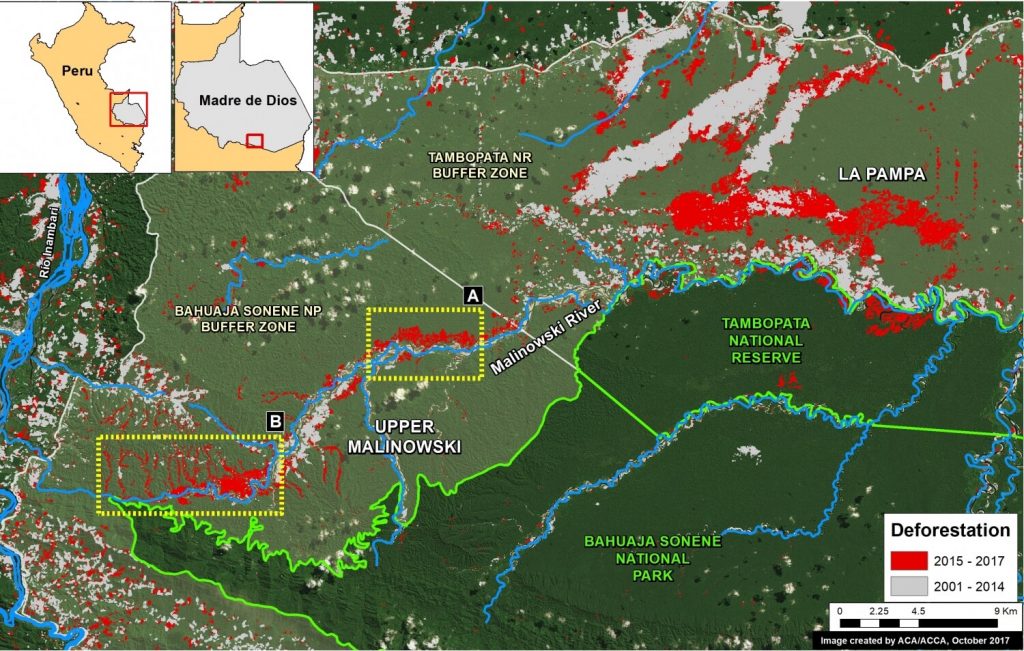

Zoom B: Southern Peruvian Amazon (gold mining)

Image B shows the loss of 756 thousand metric tons of carbon due to gold mining in the southern Peruvian Amazon (Madre de Dios region). On the east side of image is the sector known as La Pampa; west side is Upper Malinowski.

Image B. Gold mining. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

Zoom C: Southern Peruvian Amazon (agriculture)

Image C shows the loss of 876 thousand metric tons of carbon in the southern Peruvian Amazon around the town of Iberia (Madre de Dios region). Note the expanding carbon loss along both sides of the Interoceanic Highway that crosses the image.

Image C. Iberia. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

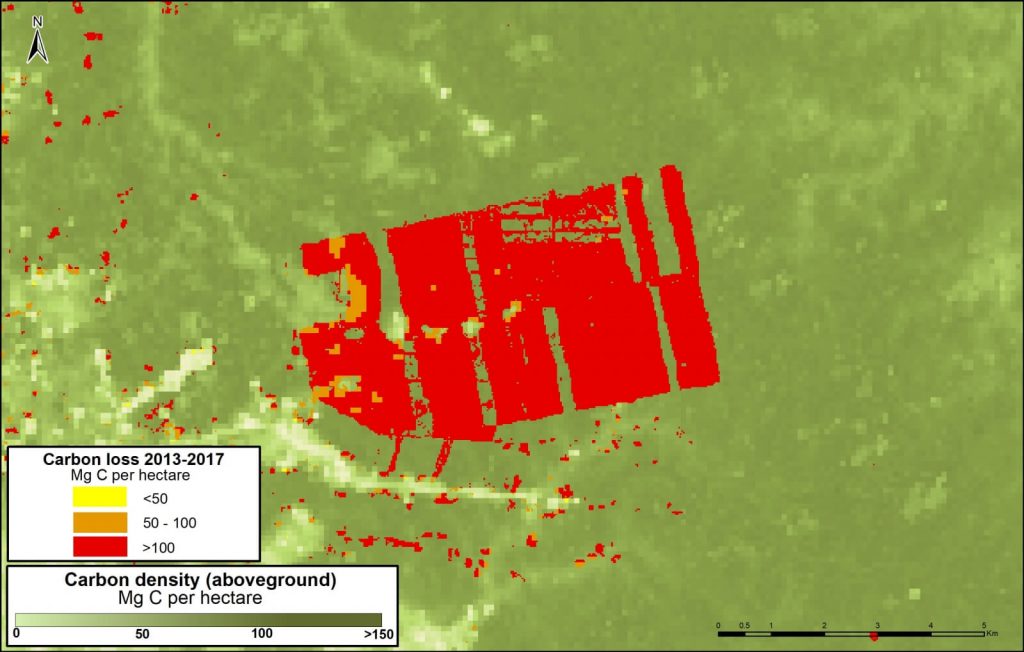

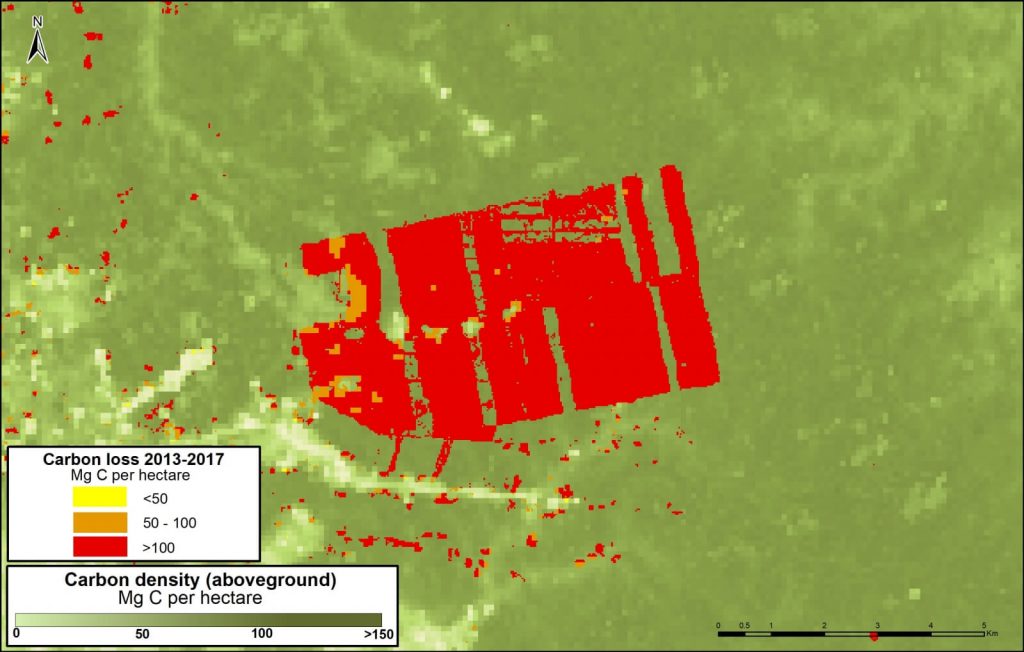

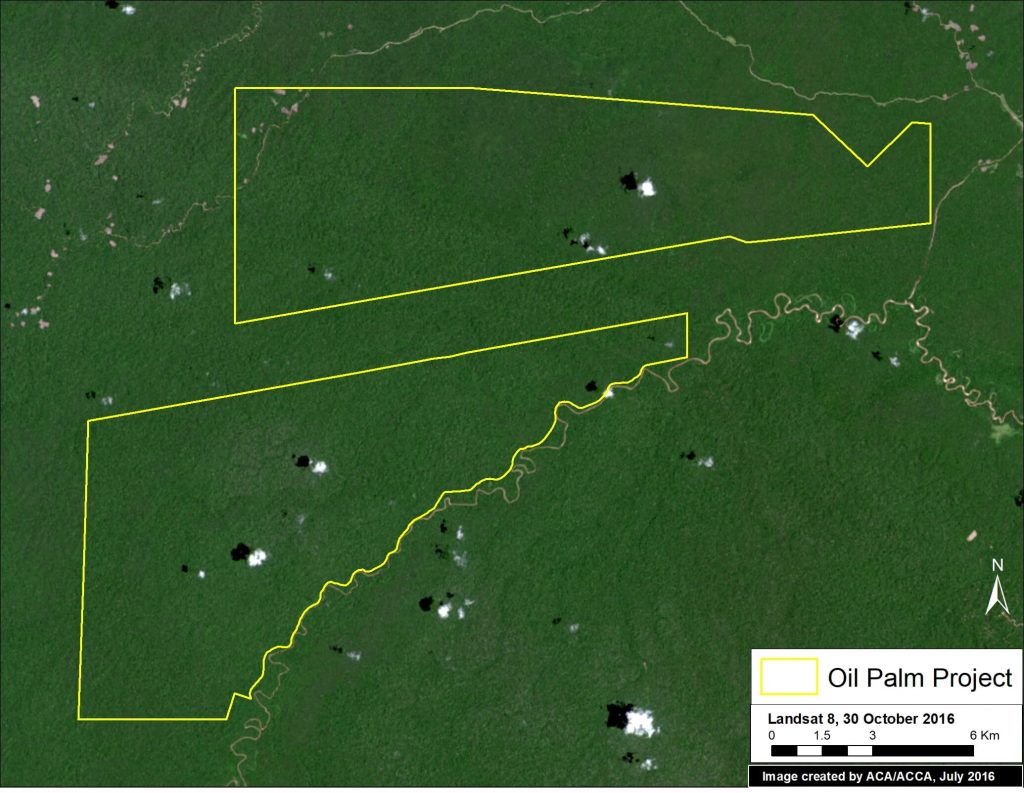

Zoom D: United Cacao

Image D shows the loss of 291 thousand metric tons of carbon for a large-scale cacao project (United Cacao) in the northern Peruvian Amazon (Loreto region). Note that nearly all the forest clearing occurred in high carbon density forest. This is another line of evidence that the company cleared primary forest, contrary to their claims that the area was already degraded.

Image D. United Cacao. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

Zoom E: Yaguas National Park

Image E shows how three protected areas, including the new Yaguas National Park, are effectively safeguarding 202 million metric tons of carbon in the northeastern Peruvian Amazon. This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

Image E. Yaguas. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

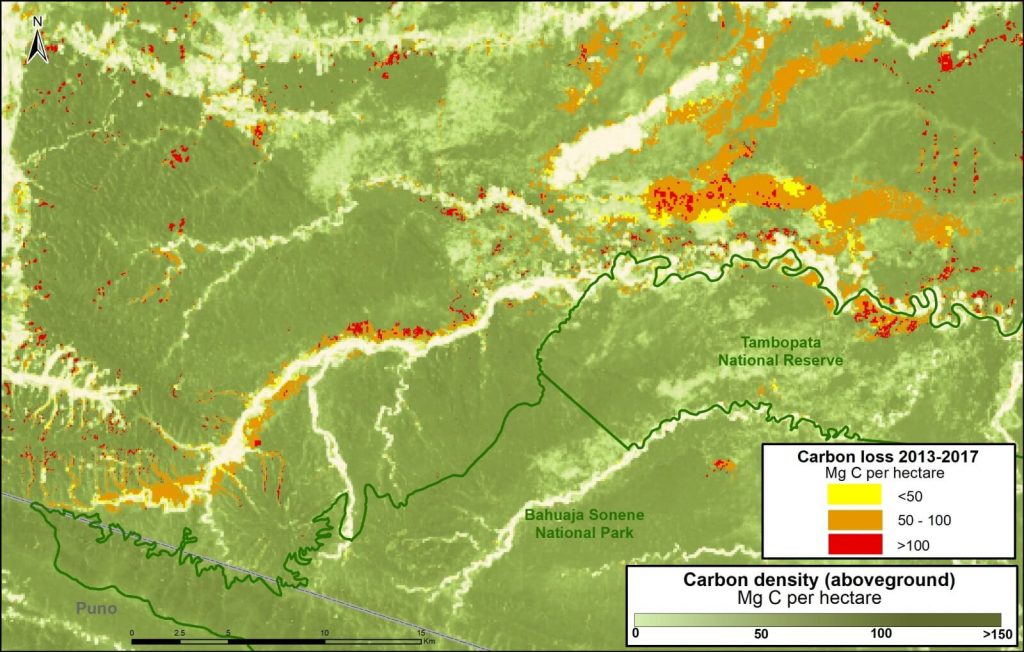

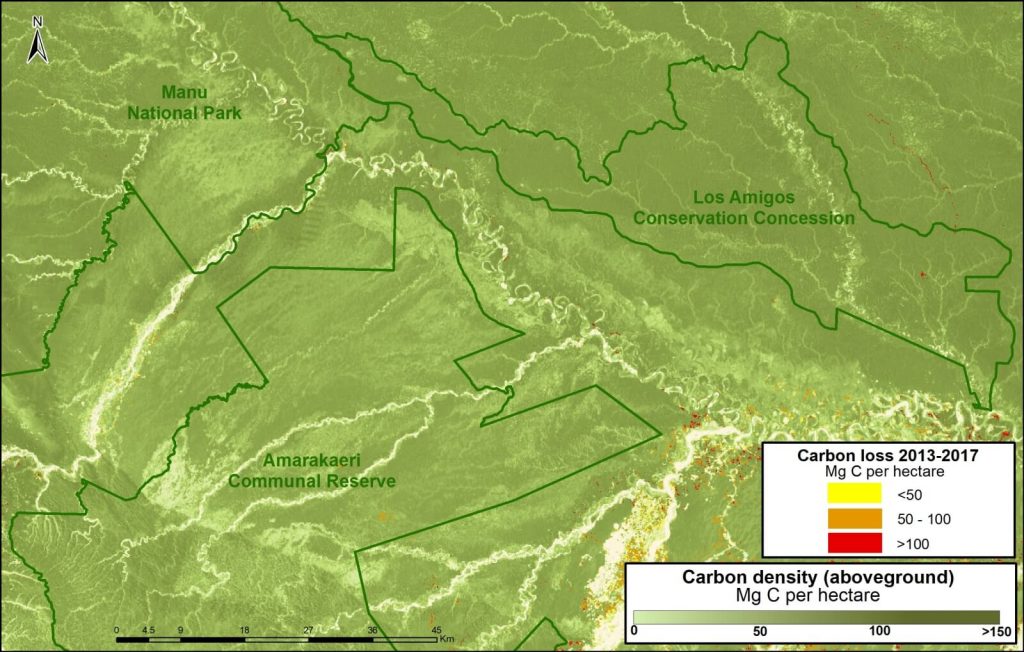

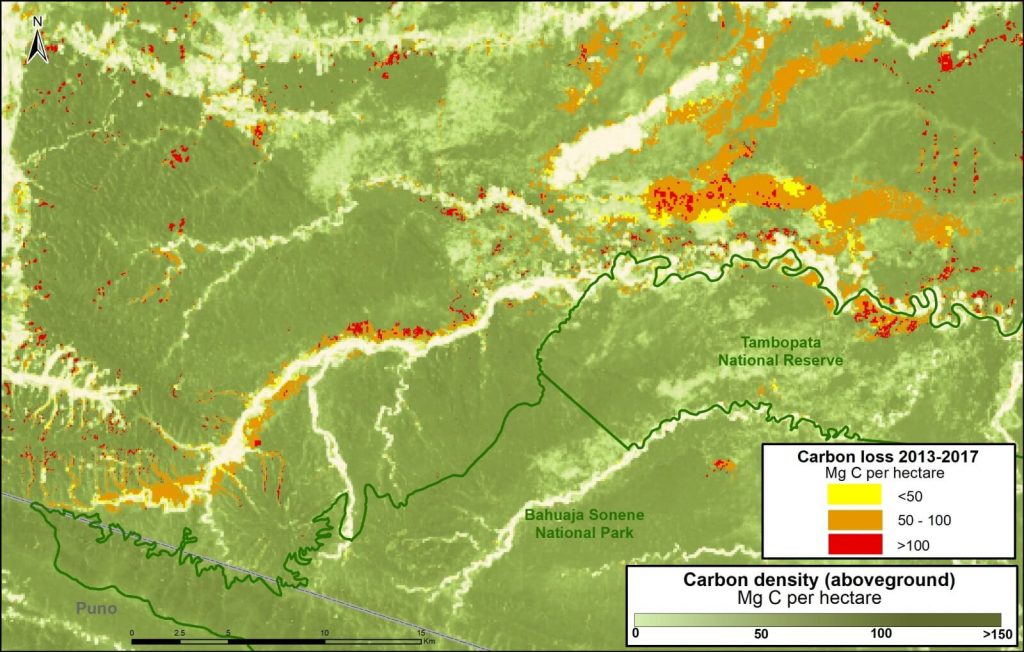

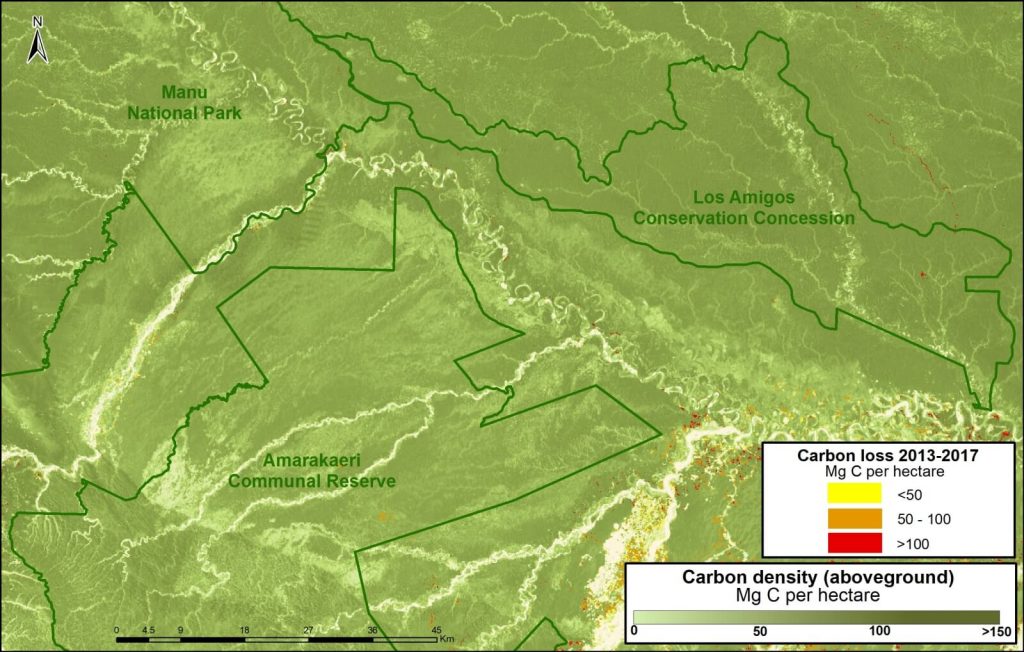

Zoom F: Los Amigos Conservation Concession

Image F shows how Los Amigos, the world’s first conservation concession, is effectively safeguarding 15 million metric tons of carbon in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Two surrounding protected areas, Manu National Park and Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, safeguard an additional 194 million metric tons. This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

Image F. Los Amigos. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

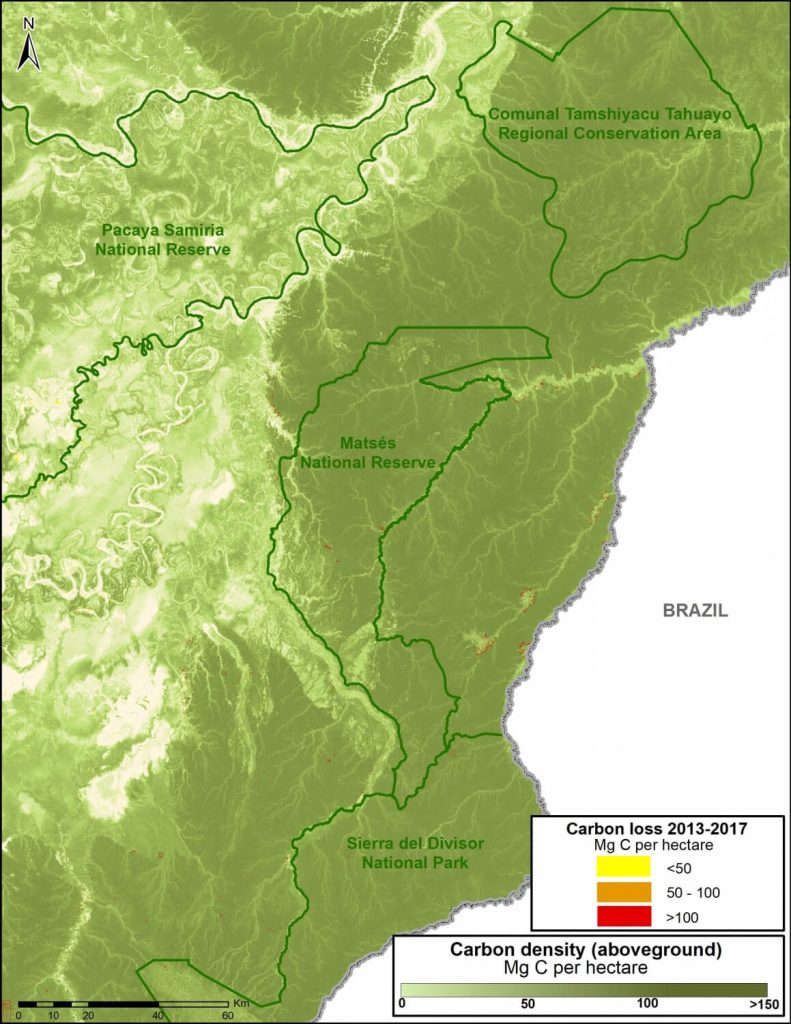

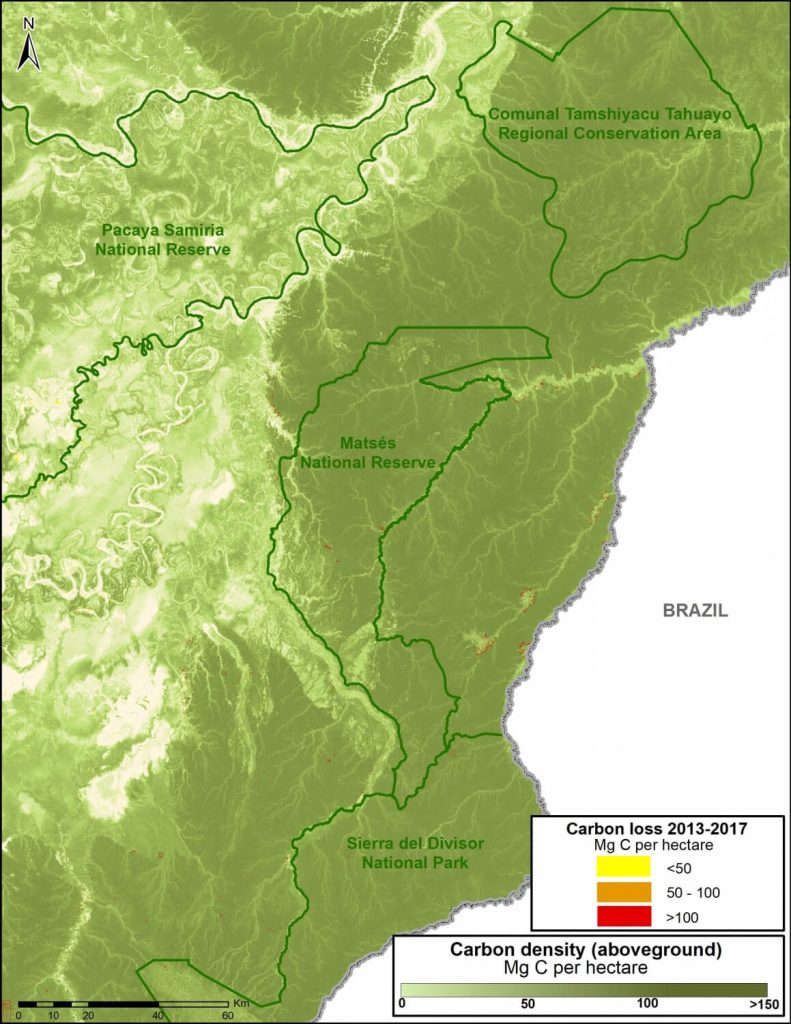

Zoom G: Sierra del Divisor National Park

Image G. Data: Asner et al 2014, MINAM/PNCB

Image G shows how three protected areas, including the new Sierra del Divisor National Park, are effectively safeguarding 270 million metric tons of carbon in the eastern Peruvian Amazon.

This area is home to some of the highest carbon densities in the country.

Methodology

Para el análisis se utilizó los datos de carbono sobre el suelo generados por Asner et al 2014, y los datos de pérdida de bosques identificados por el Programa Nacional de Conservación de Bosques (PNBC-MINAM) de los años 2013 al 2016 así como las alertas tempranas del año 2017. Primero uniformizamos los datos de pérdida de bosque 2013-2016 con las alertas tempranas del año 2017 para evitar superposición y tener un solo dato 2013-2017. Posteriormente, extraemos los datos de carbono de las áreas de pérdida de bosque del 2013-2017, este proceso permitió obtener la densidad de carbono (por hectárea) en relación al área de la pérdida de bosque para finalmente estimar el total de stocks de carbono perdido entre el año 2013 al 2017.

References

1 Baccini A, Walker W, Carvalho L, Farina M, Sulla-Menashe D, Houghton RA (2017) Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science. 13;358(6360):230-4.

2 Asner GP et al (2014). The High-Resolution Carbon Geography of Perú. Carnegie Institution for Science.

3 Boden TA, Andres RJ, Marland G (2017) National CO2 Emissions from Fossil-Fuel Burning, Cement Manufacture, and Gas Flaring: 1751-2014. DOI 10.3334/CDIAC/00001_V2017

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2017). Carbon loss from deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 81.

Loading...

Loading...